Lifestyle, treatment changes for afib

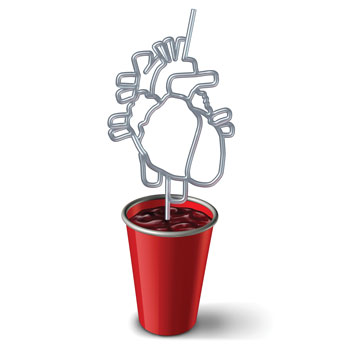

A new atrial fibrillation guideline focuses on early rhythm control and lifestyle changes such as physical activity and weight loss to slow or disrupt the course of the disease.

Physicians can help their patients slow the progression of atrial fibrillation (AF), and potentially avert its onset, with recent guidance highlighting the importance of lifestyle changes and an earlier move to implement rhythm control treatments in those who are eligible.

Atrial fibrillation, projected to impact 12 million Americans by 2030, is more likely to develop with advancing age and carries the risk of life-threatening complications. Roughly two in five adults with afib develop heart failure and one in five will experience a stroke in the years following diagnosis, according to an analysis published on April 17 in BMJ.

Studies have demonstrated the importance of earlier intervention, with a focus on maintaining sinus rhythm in patients and minimizing the burden of atrial fibrillation, according to a 2023 guideline on afib diagnosis and management from the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, and the Heart Rhythm Society, which was published in January in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Randomized studies show that catheter ablation can be selected over antiarrhythmic drugs as a first-line treatment in appropriate patients, including those who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the guideline authors wrote.

The guideline, the first comprehensive update in roughly a decade, reflects that early rhythm control has become the linchpin to reducing the risk of stroke, heart failure, and other complications, said Anne B. Curtis, MD, MACP, who coauthored the editorial accompanying the new guideline, published Jan. 2 in Circulation.

“What we know now is that if you can manage to eliminate or minimize atrial fibrillation, those outcomes will be reduced compared to patients who are not treated, or just treated with rate control,” said Dr. Curtis, a cardiac electrophysiologist and SUNY distinguished professor of medicine at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University of Buffalo in New York.

The guideline also incorporates a new classification system that includes two at-risk stages describing vulnerable patients prior to clinical diagnosis, indicating that the disease can progress along a continuum. Studies have shown that boosting physical activity, shedding pounds, and making other lifestyle changes can potentially slow or otherwise disrupt the course of the disease, said Mina Chung, MD, a Cleveland Clinic cardiologist and vice-chair of the guideline's writing committee.

Those studies, she said, “have shown the ability to reduce the burden of atrial fibrillation, reduce progression of atrial fibrillation, and even perhaps reverse some atrial fibrillation from more persistent or permanent forms to even paroxysmal or no AF.”

Risk and classifications

Slightly more than one in three adults will develop atrial fibrillation after age 55 years, according to a Framingham Heart Study analysis published in 2018 in Circulation. But an individual's likelihood ranges widely, from 22% among adults with limited risk factors and genetic predispositions to nearly 50% among those with the highest clinical and genetic vulnerabilities.

Also, the overall prevalence continues to increase, and not just because people are living longer, including with the arrhythmia, said Emelia Benjamin, MD, ScM, a Boston Medical Center cardiologist and Robert Dawson Evans distinguished professor of medicine at Boston University, as well as an author of the Circulation study.

“People also are living longer with other heart disease,” she said. “It used to be that you have heart failure and you died within five years. Now people are living five, 10, 20 years, so they are having more time to develop comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation.”

For patients, even forestalling the arrhythmia's onset can notably improve their quality of life during their remaining years, said Dr. Benjamin, noting that internal medicine physicians can play a preventive role. “If somebody has a family history of myocardial infarction, we start thinking about the risk factors and how to prevent it or postpone it,” she said. “We need to take the same attitude about atrial fibrillation.”

Unlike the prior classification approach, which was based on arrhythmia duration, the new guideline delineates stages that illustrate afib's potential progression.

Stage 1 encompasses patients who have risk factors. Stage 2 includes patients with structural heart changes or electrical findings that further boost their vulnerability, such as atrial enlargement, atrial flutter, or short bursts of atrial tachycardia. Stages 3 and 4 include substages ranging from paroxysmal to persistent and permanent AF.

Reducing risk factors is a pillar of treatment management for all four stages, including shedding weight if overweight or obese, boosting physical activity, quitting smoking, and limiting alcohol consumption, among other heart-healthy measures.

The guideline recommends at least 10% weight loss in patients with a body mass index of greater than 27 kg/m2. Salvatore Savona, MD, emphasizes the benefits of shedding pounds when patients ask about alternative treatment options. “Some people may not be interested in a medication or a procedure and they ask, ‘What can I do?,’” said Dr. Savona, a cardiac electrophysiologist and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

In one study Dr. Savona cited, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 45.5% of patients with AF symptoms who lost at least 10% of their weight reported no further symptoms and didn't require antiarrhythmic drugs or ablation. Among adults who lost less than 3% of their body weight, only 13.4% remained symptom-free without treatment.

Physicians also can educate patients about the risks of alcohol consumption both in terms of AF prevention and progression, Dr. Benjamin said. Adults who already have arrhythmia recognize the link, she said. “If you talk to people who have paroxysmal afib, they will tell you, ‘If I drink, I know I get more afib.’”

In addition, alcohol can boost the likelihood of diagnosis, she said, citing a meta-analysis of 13 observational studies published in 2022 in Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. Researchers found that consuming alcohol boosts the risk of developing atrial fibrillation starting at one daily drink for men and 1.4 drinks each day for women.

If patients decide to stop drinking, she pointed out, “they're going to lose weight, their blood pressure is going to get better, and their risk of atrial fibrillation is going to decrease. They are going to kill three birds with one stone.”

Afib management

For patients already diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, the decision about whether to start anticoagulation should depend on their calculated risk for stroke, regardless of the specific patterns of atrial fibrillation, such as paroxysmal or persistent, according to the new guideline. A scoring system, such as CHA2DS2-VASc, can assess a patient's risk annually, and this must be balanced against the risk for bleeding and patient preferences.

When a patient's stroke score falls in the intermediate-risk category, such as a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 in men or 2 in women, the guideline authors recommend that physicians look at additional modifying factors, such as the extent of the patient's AF burden and atrial myopathy (enlargement or dysfunction) and how well medication controls their hypertension. Regardless of the risk score, physicians should have a discussion with the patient, laying out the pros and cons of anticoagulation, before prescribing the medication, said David Smith, MD, FACP, a cardiologist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

For instance, if a patient has kidney or liver disease or another condition that promotes bleeding, Dr. Smith said, “you can say, ‘Look, your bleeding risk is pretty high. You're at intermediate [stroke] risk. Why don't we focus on the other changes, the lifestyle changes?’”

Along with screening for sleep apnea and ordering lab tests, such as checking thyroid function, internal medicine physicians can ensure that a patient's blood pressure is well controlled, ideally around 120/80 mm Hg, even if that requires additional medication and lifestyle changes, said Dr. Smith, who has seen patients arrive at his clinic with systolic readings well above 140 mm Hg.

“We are missing a dire call for aggressive, urgent, hard-nosed antiobesity discussions, particularly when it's a root cause of obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, pre-AF, and AF morbidity,” Dr. Smith said.

The internal medicine physician may also consider starting patients on a drug to control their heart rate, such as a beta-blocker or a nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker, in circumstances where there's a delay before they can see a heart specialist, Dr. Savona said. Plus, it's helpful if the physician orders an electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram prior to that appointment, he said.

“It can make our appointment more meaningful for the patient,” he said. “If a patient comes in and they are in afib and their ejection fraction is 20% versus 50%, that discussion will be a lot different.”

But Dr. Savona and other heart specialists stressed that a referral to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist should be regularly performed to enable the patient to better understand their antiarrhythmic medication and procedural options, including ablation or electrical cardioversion.

“The opportunity shouldn't be lost,” said Lynda E. Rosenfeld, MD, FACP, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor emerita of medicine at Yale.

“As someone remains in atrial fibrillation, there's more damage done to the atrium,” she said, including the possibility of fibrosis and atrial enlargement. “All of those things mitigate against being able to maintain sinus rhythm. The disease is going to progress more if the atrial fibrillation continues.”

Rhythm vs. rate control

Patients considered appropriate candidates for ablation as first-line treatment include those who have been recently diagnosed with fewer comorbidities and minimal atrial enlargement, according to the guideline. Younger patients are more likely to benefit, but the procedure has improved outcomes in research studies even among patients with median ages in their 70s, the guideline authors wrote.

Patient preference certainly plays a role, and not all optimal candidates are interested, Dr. Rosenfeld said. “They can say, ‘There's no way you are going into my heart with a catheter.’ It may in that case make sense to treat them with an antiarrhythmic drug to try to maintain sinus rhythm and see how it goes,” she said. “Develop a relationship with that patient and then maybe in a year they're having more atrial fibrillation, and it becomes more appropriate and they are agreeable to the procedure.”

Either rhythm control approach is reasonable if it proves to be effective, Dr. Curtis said.

“If you do rhythm control with antiarrhythmic drugs and they minimize the amount of atrial fibrillation a patient has, there's no advantage to going to ablation as far as we know at this time,” she said. “I truly believe that. I think the lower the afib burden, however you get there, is fine.”

The one exception, as Dr. Curtis noted in her editorial, involves patients who also have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, as ablation has been associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes, she wrote.

The new atrial fibrillation management guideline also underscores the need to better address health disparities by making guideline-directed therapies equally available across all populations, said Dr. Benjamin, a guideline coauthor. “We put a line in the sand that this is important, and we need to address it,” she said. “It's saying that if we want to have good outcomes population-wise, we need to practice this.”

Studies have shown that some populations may have less access to the latest approaches. One analysis, which looked at treatment for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, found that Black adults were less likely to get rhythm control treatment than White adults, according to the findings, published in 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

Meanwhile, some adults continue to live with undiagnosed atrial fibrillation, an estimated 11% of cases, according to an analysis published in May 2023 in Clinical Cardiology. The proliferation of smartwatches and other wearable heart monitoring devices may flag more cases of atrial fibrillation moving forward, including at a younger age, the guideline authors wrote. But the technology, they cautioned, should not be relied upon for diagnosis.

The devices can be “a useful tool,” one that physicians can follow up on by ordering an electrocardiogram or asking patients to wear an ambulatory monitor, Dr. Savona said.

If a patient's atrial fibrillation is detected incidentally in other circumstances, such as during hospitalization for an infection or a noncardiac illness, physicians can adopt a similar monitoring approach, Dr. Savona said. The new guideline emphasizes the risk for recurrent atrial fibrillation in those scenarios.

“We used to say, ‘This is just an acute illness and afib is not a major issue for this patient,’” Dr. Savona said. “But there are certain patients who will go on to develop afib out of that patient population. This can be an early warning sign that they may actually have clinical afib, rather than just afib related to an acute illness.”