A shingle or a billboard? Changes in physician practices

Physician employment has accelerated over the last two decades as the health care system has evolved.

The days when a newly graduated physician could hang out a shingle and start a practice are now a distant memory, as more and more physicians are compelled to or choose to seek employment by hospitals, health systems, or large corporate practices. New or even long-practicing physicians may be incentivized by attractions such as financial stability and relief from administrative burdens, changing the practice of medicine to be more geared to an employment or contractor model than traditional private practice.

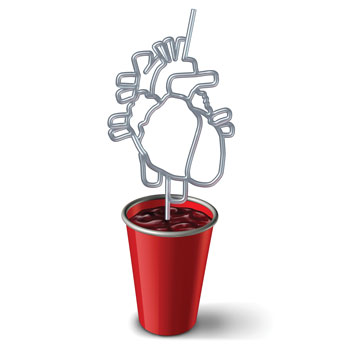

As such, the employer effectively becomes an intermediary between the patient and the physician, which creates unique and complex social and ethical dynamics for the doctor-patient relationship. I would like to explore some of these issues and consider how employed physicians can navigate the moral and ethical challenges that they may face as they care for patients.

Physician employment has accelerated over the last two decades as the health care system has evolved. Factors such as rising costs to run a practice, growing regulatory demands, and the increasingly complex milieu of patient care have led to a death knell for small independent practices. Many of these practices have been consolidated into larger and larger medical groups, health care systems, and corporate entities such as private equity firms, leaving former physician-owners as the employees of the new system or causing them to exit the practice of medicine altogether. Likewise, most newly graduated physicians find it virtually impossible to open or join a small practice where they have professional autonomy and independent control.

This loss of autonomy is a huge source of dissatisfaction for many physicians. They now must follow institutional protocols, meet productivity metrics set by nonphysician administrators, and adhere to institutional standards and guidelines often set to minimize cost and to increase efficiency. This “industrial” work model is often in conflict with a physician's obligation to their patients and sense of independence and judgment, and it can create a feeling of disempowerment and frustration, leading to a “hamster-wheel mentality” and burnout.

Indeed, the rise in burnout among physicians parallels the decline in private practice ownership and increase in physician employment. This is likely due in part to the administrative burdens and pressures to meet administrative demands such as EHR use and productivity expectations. Burnout creates emotional exhaustion and depersonalization that impact the well-being of physicians as well as straining their ability to professionally and empathically care for their patients. Can an employed and burnt-out physician continue the Oslerian tradition of putting the patient first? Can they continue to ensure that their clinical judgment is used solely for the benefit of the patient, rather than influenced by the dictates of their employer's organizational goals?

While it is easy to see many of the problematic issues associated with physician employment, there can also be a silver lining for physicians and patients. Employed physicians generally have resources and support that may not be available in private practice. Access to technology and specialized consultative services may result in better patient care and better outcomes, while administrative support for tasks such as billing, coding, and compliance can reduce the burden on physicians, enabling them to spend more time taking care of patients or on their personal lives and careers. Other benefits such as improved financial security, comprehensive benefits, and malpractice insurance make employment an attractive proposition.

There are also some less tangible benefits of physician employment. Physicians working in large systems find it easier to collaborate and connect with professional colleagues, engage in education, pursue personal professional development, and interact with other health care professionals. These interactions can reduce the sense of professional isolation and detachment that sometimes exists in private practice and enhance personal professional fulfilment. Ultimately, this collective sense of professional commitment likely benefits individual patients and can improve population outcomes.

Physicians, however, need to guard against the erosion of the personal and direct doctor-patient obligation that can occur in the employment model. Physicians must not neglect the moral obligation that is enshrined in the Hippocratic Oath irrespective of their employment status. Their clinical judgments must be solely based on the best interests of the patient, regardless of organizational pressures. They must continue to advocate for patients whenever what is best for the patient conflicts with institutional policies or financial considerations, as well as to advocate for exceptions to rules that may limit patient access to high-quality, evidence-based care.

When caring for patients in large institutions and health systems, physicians must continue to adhere to the four basic principles of medical ethics: beneficence, nonmaleficence, patient autonomy, and justice. They must ensure that patients are fully informed of treatment options, potential risks and benefits, and alternatives to care, including access to a second opinion or transfer to another institution if necessary. They must not attempt to influence the patient to make decisions to benefit the institutional bottom line, for example, emphasizing certain procedures or treatments based on financial incentives, as explained in ACP's 2021 policy paper, “Ethical and Professionalism Implications of Physician Employment and Health Care Business Practices.”

Employed physicians should also pay great attention to the potential for conflicts of interest, particularly with regards to patient referrals, selection of treatments and procedures, and restriction or use of selected medications. Due to the inherent conflict between institutional financial goals and patient care needs, preventing or avoiding conflicts of interest requires a proactive and careful adherence to standards of professional integrity and, where necessary, guidance from institutional ethicists or ethics committees. Employed physicians must also maintain their commitment to providing evidence-based care while challenging directives that may compromise and limit patient care.

Even though many physicians have traded the traditional shingle on the door for the big health system billboard, the obligation to provide the best care possible for each individual patient remains. Organizational structures should not intrude into the doctor-patient relationship, and physicians must continue to take personal ownership of every interaction with their patients. As employees of this or that prestigious-sounding health system, we must remember that despite the beautiful waterfall in the lobby and self-playing piano in the cafeteria, the patient walks in the door seeking care from us, the physicians, not from “the system.”