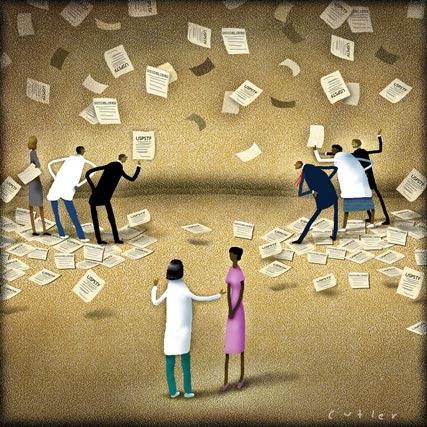

Med schools promoting care for underserved

To encourage primary care careers, medical schools are offering students shortened specialty rotations in favor of fast-track graduation, half-tuition forgiveness and having students follow patients wherever they go in the health system. Different teaching models emphasize continuity of care over snapshots of diagnoses, and place students in the clinics where they can fulfill the nation's need for rural care.

Third-year medical student David S. Keith is moving fast through his training.

“I was involved in patient care by my fourth month [of medical school],” he said. “By the time I hit my first official rotation in March of my second year, I had been in a doctor's office so many times as a medical student that I hit the ground running.”

By next year, when his peers begin moving through their elective rotations, Mr. Keith will already be a family practice resident, that much closer to his goal of becoming a rural primary care physician. “I love the full spectrum of family medicine, where you can deliver babies one moment, next care for parents and families, and support those in need of palliative care,” he said.

His rapid progress was made possible by the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine's (LECOM) Primary Care Scholars Pathway, a program that allows students who want to practice primary care to graduate from medical school in three years instead of four.

The pathway is one of a number of innovative experiments currently under way at U.S. medical schools. Physician shortages in primary care and rural areas, as well as a perceived need for more on-the-ground training, have inspired these schools to offer some new ways to study medicine.

Med school, condensed

The three-year pathway at LECOM is perhaps the most revolutionary of the changes. Students enter the program 12 weeks into medical school, after a series of interviews has established that they are self-starters and team players.

“It's not for everyone,” said second-year student Narissa Whitelaw. “It's more independent-study-based.”

Much of the time that the students aren't spending in class is filled with clinical medicine. During the first year, the students spend half-days shadowing primary care physicians. By the second year, the students have chosen one of these practitioners as a mentor. The second year also comes sooner. Students on the primary care pathway give up eight of their 10 weeks of summer vacation and all but a couple of days of the winter holiday break.

When LECOM administrators set out to shorten medical school, vacation was one of the few things they knew they could safely eliminate. “We knew no accrediting body would like it if we decreased the amount of basic science,” said Richard Ortoski, DO, chair of the department of primary care education.

Elective rotations were the other major cut, with the total dropping from 24 to 16. “Our students have only two medical selectives. They have one emergency rotation instead of two. They have one surgery,” said Dr. Ortoski.

Rotations are less necessary because the program's participants have already chosen their specialty. Every student who enters the pathway pledges to practice primary care for at least five years after residency. The only permissible subspecialties are geriatrics and osteopathic manipulation.

Obviously, the students who apply have to already be set on primary care. In addition to the required pledge and an accompanying financial penalty, it would be difficult to get into a subspecialty without having completed the relevant rotations. But the program could help remedy the issues that cause students who are initially interested primary care to change their minds, according to Dr. Ortoski.

“Students are not interested in primary care because it's the same amount of time in medical school, the residencies are three years, and then you get out and you get paid so much less than any subspecialist. We can't change the government and how they pay us, but how can we make it easier?” he said.

The solution: LECOM charges pathway students for only three years of tuition, unless they break their pledge not to specialize. The shorter program means less time spent without a paycheck. “I'm going to come out with less debt than average among my compatriots,” said Mr. Keith.

Northern exposure

If his compatriots are from Maine, however, they also have a new opportunity to attend medical school less expensively and gain experience caring for underserved patients. Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston and Maine Medical Center in Portland have collaborated on a new Maine track that includes half-tuition scholarships.

“We do have, probably like everybody else, an issue of not enough primary care as well as subspecialists in all parts of the state. We tend to rank either 49th or 50th in the country in terms of medical students applying and going to allopathic medical schools,” said Robert G. Bing-You, FACP, associate professor of medicine at Maine Medical Center.

The Maine track, currently in its first year, has enrolled 31 students, two-thirds of whom had an existing connection to Maine. They are students at Tufts and complete much of their education with their classmates in Boston, but beginning with a two-week orientation before the start of school, they also spend a lot of time in Maine.

That prospect appealed to Coley Barbee, a member of the program's inaugural class. “I grew up in a small town in downeast Maine,” she said. “I wanted to come back, but I felt like the educational pursuits I wanted weren't available in the state of Maine.”

Next year, Ms. Barbee and her classmates will go to Maine two days a week to work with rural preceptors, who are mostly primary care physicians. During their third and fourth years, the students are in the state full-time on rural clerkships. “Students can spend nine to 10 months in a small community hospital, two to four students in each site. They'll really be immersed in a rural community,” said Dr. Bing-You.

Unlike the LECOM program, the Maine track doesn't require any commitment regarding students' specialty or residency choices. Instead, the plan is to expose them to primary and rural care. “We think it's very difficult for a student, even during medical school, to have a good sense of what career fits well,” said Dr. Bing-You. “We want to show the students they can have a very productive career in a community or rural site.”

Although the primary care shortage is a concern, the program's real focus, since it is in part financially supported by the state, is on Maine. “We recognize primary care is a big issue, so we do want to try to expose the students to good role models and get them thinking about primary care,” Dr. Bing-You said.

Community learning

Exposure to primary care and underserved areas is a core component of a new medical school in Arizona. Two years ago, A.T. Still University, an osteopathic school in Missouri, opened a School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (SOMA). The university had already established the Arizona Schools of Health Sciences and Dentistry & Oral Health.

“They [leaders of A.T. Still] felt that they needed a venue to supply more physicians in Arizona,” said Douglas Wood, DO, PhD, dean of SOMA. Many of the school's students, however, actually spend relatively little time in Arizona.

“Our students are with us for only one year and then they leave and go out into community health centers spread out literally across the country,” explained Dr. Wood. About 10 students are placed at each of the 11 participating health centers and their second-year education is conducted through distance education technology. The school hires physicians at each facility to instruct the students as well.

During the third and fourth years, the students stay at the community facilities to do their standard rotations. “Their homes for years two, three and four are those community health centers,” said Dr. Wood.

Although the program doesn't have an explicit focus on primary care, the administrators' hope, once again, is that exposure will have an impact. “What we're trying to do is by embedding these students in that setting, the possibility of having more of them come back and practice in primary care areas will be enhanced,” Dr. Wood said.

The university does encourage the students, whatever specialty they choose, to commit to some amelioration of physician shortages. “One of the things we ask them to do is that they would spend at least one year of their practice life serving the underserved in this country. How many of them will actually do this? I don't know,” said Dr. Wood. But the Arizona dental program, which has been operating on the same model longer, reports 35% of graduates working in community health centers.

The school is also trying to produce better all-around clinicians by employing the Clinical Presentation curricular model. This model bases all education, including basic science, around the problems with which patients present, such as headache or chest pain, moving on from there to the diseases that could cause these presenting problems.

“Students learn by studying the ways patients present to physicians,” said Dr. Wood. “They start out on day one with clinical medicine. We believe they will be better medical problem-solvers and better diagnosticians.”

Education from patients

Starting soon, students from Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons will also have the option of a less disease-focused educational track. Bassett Healthcare in Cooperstown, N.Y., has been educating medical students from area schools in innovative ways for a while, but recently began recruitment for a new program with Columbia.

Under the program, students will complete their basic science and foundational classroom education in 18 months instead of two years, and then relocate to Cooperstown beginning Jan. 1 of their second years.

“We have the students come and do some really fast rotations—two weeks of inpatient pediatrics, two weeks of inpatient psychiatry, three weeks of surgery, three weeks of medicine. They're starting to learn a lot about being a doctor,” said Henry Weil, MD, assistant dean for education at Bassett.

Then the students start learning about being a patient. When a student meets a patient in the course of a rotation, the student adds the patient to her longitudinal panel. The next time the patient is seen by anyone in the health system, the student goes along. The patient may be seen on the first encounter to discuss his hypertension. When he comes back for a cardiac catheterization or even a knee replacement, the student accompanies him.

“They are not seeing people as snapshots and they are not seeing diseases as snapshots. They're doing something that no doctor has hitherto done in training, even in a specialty,” said Dr. Weil.

The setup creates mutual bonds between students and patients. “[The patients] see the students as an advocate for them. There are patients who won't see their doctor unless their student is present,” said Dr. Weil. “As [the students] are studying a disease, it's not in the abstract anymore; it's for this person that they have a relationship with.”

The program also makes an effort to introduce students to the nonclinical aspects of health care. They sit on committees working on performance improvement and meet with the hospital CEO and other administrators. “They see all the warts and the problems and the struggles. They're bouncing back and forth between doing it and learning the theory behind it,” Dr. Weil explained.

At the end of the program, the students spend four weeks on their primary care rotation and get a chance to try out the skills they've picked up. “Students are watched to see how far they can take care of a patient. It lets the students know how much they've learned,” Dr. Weil said.

The exposure (and a $30,000 per year tuition break) may encourage students to consider primary care, according to Dr. Weil. “This medical school track may very well end up with a higher number of people going into primary care, but we're not trying to talk anybody into anything. We're trying to create an environment where they figure out what within medicine is the best fit for them.”

It's a goal common to all medical schools, but a few universities are changing the model in an effort to find more effective and faster ways to accomplish the mission. Their degree of success won't be visible for some years, but in the interim, it's clear that students appreciate the effort.

“It feels like I've been in school forever, so the sooner I can finish and get out there and start actually practicing medicine, that's the most rewarding part,” said second-year student Ms. Whitelaw.