Calmer talk needed about mammography

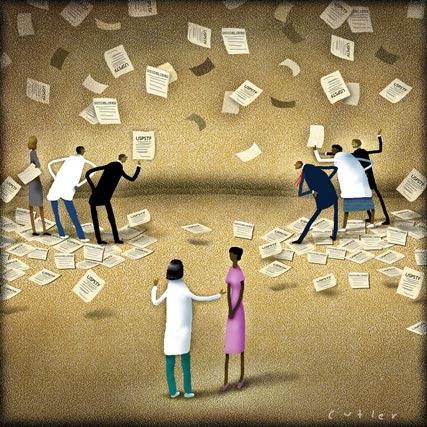

Controversy about implementing new mammography guidelines shouldn't cloud talks between doctors and the women they counsel. Clarify what the guidelines really say, and share the decision-making with patients, experts counsel.

For many physicians, the controversy following the recent release of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's (USPSTF) breast cancer screening recommendations was another reminder that practicing evidence-based medicine requires tempering science with the art of individualized patient care.

“I think the average doc out there is trying to make sense out of this just like everyone else. They are trying to simultaneously hold on to opposing viewpoints and make sense of them,” said Paul Han, FACP, MPH, a clinical investigator at the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

“When the landscape of guidelines is conflicted, physicians are pushed to say that this is an area of scientific disagreement and that decisions have to be individualized. It pushes us to inform and share decision making with patients,” Dr. Han said.

Larissa Nekhlyudov, ACP Member, MPH, recently published a dialogue model to help physicians engage women in their 40s in decision making about breast cancer screening.

“My research has found that women want to know the potential harms and benefits of screening mammography, but this information is often not provided by their physicians. Hopefully this controversy brings out to women and to physicians the fact that there has been and perhaps always will be uncertainties about screening women in this age group. Informed decision making needs to occur,” said Dr. Nekhlyudov, director of cancer research in the department of population medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston and a practicing general internist at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates.

Experts often disagree

When the USPSTF's recommendations were published in Annals of Internal Medicine last November, the details were somewhat different from its 2002 recommendations in several key areas. In brief, the USPSTF now recommends the following:

- Women aged 40 to 49 who are not at increased risk due to underlying genetic mutation or history of chest radiation should not be screened routinely. This is a change from 2002, when the USPSTF recommended mammography every one to two years for all women older than 40.

- Women aged 50 to 74 should be screened every two years.

- The advisability of screening women aged 75 and older and of clinical breast examination beyond screening mammography in women older than 40 is unclear because of insufficient evidence.

- Teaching women to conduct breast self-examination is not recommended.

The first recommendation has been the most controversial. The USPSTF said that even though the “benefit of screening seems equivalent for women aged 40 to 49 years and 50 to 59 years, the incidence of breast cancer and the consequences differ … and there is moderate evidence that the net benefit is small for women aged 40 to 49 years.”

These guidelines are not far afield of ACP's, which recommended in 2007 that any decision about screening women aged 40 to 49 must be based on a woman's preferences and breast cancer risk profile. ACP also recommended further research to clarify the net benefits and harms of breast cancer screening for women aged 40 to 49.

John Benson, DM, consultant breast surgeon at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, U.K., and editorial consultant for module updates of ACP's Physicians' Information and Education Resource (PIER), said the recommendations harmonize with European ones.

“I broadly welcome these recommendations and, in fact, view them as somewhat overdue,” he said. “Within the international breast community it is generally accepted that clinical trials to date support the conclusion that mammographic screening reduces the risk of death from breast cancer in women aged between 50 and 69 years. For women between 40 and 50 years of age, there is evidence for effectiveness of screening in terms of mortality reduction, but it takes rather longer for that benefit to emerge. Moreover, the magnitude of the mortality reduction is only about 15% compared to 20% or more for women older than 50.”

ACOG and ACS weigh in

Several U.S. medical groups have disagreed with the USPSTF recommendations. As soon as the embargo was lifted, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Cancer Society (ACS) fired back with their own statements.

ACOG continues to recommend mammography screening every one to two years for patients in their 40s, annual screening for women 50 and older, and continued use of self-examination. The ACS stands by its recommendation that annual mammography screening begin at age 40.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has urged all women beginning at age 40 to discuss mammography with their doctors “to understand the benefits and potential risks, and determine what is best for them.” By age 50 at the latest, according to ASCO, “all women should receive regular mammograms.”

Heidi Nelson, FACP, MPH, lead investigator of the systematic review to update evidence for the USPSTF, said that the evidence is limited and “does not address every important issue about screening.”

Dr. Nelson, of the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center at Oregon Health & Science University, said that “differences in guidelines often reflect differences in perspectives and interpretations of evidence. The USPSTF represents an evidence-based view by experts in screening and prevention, and most of them are also clinicians in primary care fields of medicine.”

Now what?

Dr. Han has examined primary care physicians' perceptions of different clinical practice guidelines for breast and cervical cancer screening. His research has found that the proportion of physicians who consider ACOG and ACS guidelines influential is greater than the proportion of those who regard USPSTF or other medical societies' guidelines as influential.

However, about 62% of primary care physicians perceive multiple, rather than single, guidelines as influential. Most of these physicians endorse combinations of guidelines that are actually conflicting in their screening recommendations.

“Physicians say that ACOG and ACS are very influential, but they will simultaneously say that the ACP or the American Family Practice or USPSTF guidelines are also important,” Dr. Han noted.

Doctors seem to be trying to integrate the diverse viewpoints. Guidelines, of course, are based on population analyses, the greatest good for the greatest number, Dr. Han said.

“What is good for the aggregate may not always be good for the individual. That is the fundamental tension within all of this that is difficult to deal with. Hopefully this will lead to patients and doctors having an informed conversation.”

Antonio Wolff, FACP, associate professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and a PIER author on breast cancer, agreed that the controversy “will force doctors and patients to become more educated about what mammography screening can and cannot do.”

Other authors connected with PIER's breast cancer screening module said that the controversy highlights the limitations of mammography as a screening tool. According to Tracy Battaglia, FACP, MPH, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University School of Medicine and a PIER author, basic knowledge of breast cancer biology that would allow detection of preclinical breast cancer is lacking.

“Physicians will certainly be having longer discussions with their patients. Ultimately we believe most physicians will err on the side of screening,” said Dr. Battaglia, speaking on behalf of Teresa Cheng, MD, Karen Freund, MD, and Sarah Lane, all authors on PIER's breast cancer screening module.

In their disagreement with some of the data used by the USPSTF panel, Dr. Battaglia and colleagues said the new guidelines have potential to change current practice. “These new guidelines provide the public with more reason to doubt their provider recommendations and to support the many women who are ambivalent about screening, regardless of their risk profile.”

Individualized patient care

Karla Kerlikowske, ACP Member, in an editorial published in the same Annals of Internal Medicine issue as the USPSTF guidelines, wrote that improvement in risk assessment in primary care and mammography facilities is needed, thus “providing tailored recommendations for prevention based on individual risk.”

“We urgently need risk models with better discriminatory accuracy that can correctly identify persons at all levels of risk,” wrote Dr. Kerlikowske, professor of medicine and epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco.

Most specifically, she said in an interview, current work is under way to develop these new risk models. “All have breast density in the model, a strong risk factor for breast cancer.” Health professionals must be educated about how best to communicate information about breast cancer risk and the potential benefits and harms of intervention, and must help women understand their choices, she said.

Ann H. Partridge, ACP Member, and Eric P. Winer, MD, both at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, argued in the New England Journal of Medicine that the USPSTF guidelines should stimulate more “personalized cancer screening … [and that] personalized risk assessment and screening tailored to risk are our goals for the future.”

They advised that women at average risk should make a decision through conversations with their physician about which screening program is “best suited to their personal preferences and physical condition.”

Younger women will undoubtedly be questioning their physicians about the appropriateness of breast cancer screening, given the level of media attention to the USPSTF guidelines and the resulting controversy. The model that Dr. Nekhlyudov and her colleague, Clarence H. Braddock III, FACP, created is a first attempt at a recommended dialogue that is both evidence- and theory-based and can be used to educate women in their 40s about breast cancer screening, as well as individual level of risk. It involves several steps:

- Discuss the patient's role. Does the patient understand what is involved in screening? Does she have questions? Does she want to hear more about screening?

- Discuss the clinical issue and what the decision involves. What does the patient think about screening? Does she have any questions?

- Discuss the different types of screening. Explain mammography, and discuss any questions about other types of screening.

- Discuss the benefits, possible harms and uncertainties of screening.

- Assess the patient's understanding. Does she have questions?

- Explore the patient's preference. Should the mammogram be scheduled or does the patient need more time to think about it?

Dr. Nekhlyudov adds that the most important risk factors for breast cancer screening include:

- family history of breast cancer,

- age of the patient,

- history of abnormal breast biopsy,

- having first child after age 30,

- known BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, or

- having a previous mammogram that showed dense breasts.

According to Suzanne Fletcher, MACP, of Harvard Medical School, physicians need to find better ways to communicate information about what the real risks are.

“Women, especially younger women, tend to way overestimate their risk of getting breast cancer. They see this 13% lifetime risk statistic and don't understand that this is not the case when they are in their 40s, their 30s or their 20s. They don't understand what lifetime risk means.”

A clinician should first help patients establish their individual risk by looking at family history.

“We have to help women who are at average risk, and most of us are, to understand their risk of breast cancer and what screening does in terms of saving lives. The health care profession needs to do a lot of work to find out how we can communicate the numbers and probabilities in a way so that women who have not had a biostatistics course can understand it,” Dr. Fletcher said.