Bringing patients onto the diagnostic team

Patients and physicians may look at clinical diagnoses, and misdiagnoses, very differently, a recent study found.

Patients and physicians may look at clinical diagnoses, and misdiagnoses, very differently, a recent study found.

As part of a larger quality and safety improvement initiative, researchers in Texas and Pennsylvania identified primary care patients who were considered at risk for diagnostic concerns based on unexpected visit patterns and had them review their own medical records.

“We were curious [whether] if given the tools, would patients review their medical record … and if they do, can we compare their perception of the notes to traditional chart review from a clinician perspective? When patients look through their medical record with a safety lens, what do they report?” said lead author Traber D. Giardina, PhD, MSW.

A total of 467 patients of Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania used a structured data collection instrument called the Safer Dx Patient to review their clinicians' notes in the medical record. Two clinical chart reviewers did the same using a different structured instrument developed for clinicians. The researchers then evaluated whether the reviewers and patients identified the same concerns.

The clinician chart review identified 31 (6.4%) diagnostic concerns, and of these, only 11 (21.5%) overlapped with the 51 patient-reported diagnostic concerns. Themes identified from clinician chart review included failure to work up symptoms, failure to consult or refer to a specialist, and failure to order tests, while themes from patient review included communication issues, accuracy of the clinical notes, and a feeling that the clinician was not taking them seriously. The results were published Sept. 5 by the Journal of General Internal Medicine. The authors concluded that clinicians and patients may not always have the same shared mental model of the diagnostic process and even when they both agree that there is a diagnostic concern, their definitions can be very different.

Dr. Giardina and coauthor Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, both from the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, recently talked to I.M. Matters about the study's results.

Q: Were the results what you expected?

A: Dr. Giardina: I was surprised that when we found cases where the patient and the clinical chart review agreed there was a diagnostic concern present, they didn't identify the same issues. … I thought we would find more concordance between the reasons for the diagnostic concerns, but patients, in our sample, focused on that interpersonal interaction. They know something is wrong, but they're not linking it to the same thing that the chart review found was wrong. I find that very interesting because we are getting closer to evidence that these interpersonal interactions between doctor and patient have very real clinical implications in diagnostic safety.

Dr. Singh: I wasn't really surprised by the results. We knew that patients' perspectives are different based on prior work and interviews. Patients give you a different perspective on why they were misdiagnosed, or how they experienced diagnosis. Plus, sometimes it's about the language we use and how we communicate it. A patient may think they were misdiagnosed because they were told they had “viral illness” and later see the medical name of the viral syndrome and think that's what their real diagnosis was. Both things are true; it wasn't that the diagnosis was missed.

Dr. Giardina: As another example, from a clinician's perspective, it probably seems obvious that a patient could have symptoms at one visit that evolve to a new diagnosis at the next visit, but for patients that can be confusing. Without clear communication about diagnostic evolution, a patient may be left feeling like they were misdiagnosed. It shows that what is left unsaid will inevitably be filled in with whatever information is available. If the patient thinks that something went wrong, the downstream consequence of that is mistrust. If you really think your clinician didn't share this possibility or didn't diagnose you correctly, you may not come back. When we use an intersectional lens and prioritize health equity, that has potentially devastating consequences for marginalized and underserved patients.

Q: How can physicians better communicate to patients what's happening during the diagnostic process?

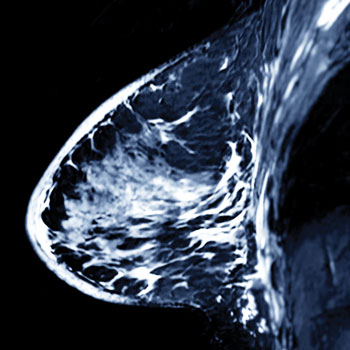

A: Dr. Singh: One thing we've been advocating is more communication of uncertainty directly to the patients or families, just because it enhances the notion of understanding the diagnostic process. People tend to think diagnosis is black and white, but often it's not. It's nearly always in shades of gray. Only at times you're nearly certain of the diagnosis confirmed by pathology or radiology, and often it's an evolving diagnostic process that unfolds over time.

The issue with communicating uncertainty is that some clinicians may feel uncomfortable with it. We did a study where if a clinician communicated uncertainty very explicitly to patients, for example by saying “I don't know,” patients tended to rank the clinician lower in terms of trust versus when uncertainty was communicated in an implicit fashion, saying “It could be this, it could be that, we're going to do this.”

Q: What are some tips for better acknowledging and connecting with patients?

A: Dr. Giardina: Sometimes it may be just a matter of looking at people when they talk, being thoughtful about tone and physical touch. In our work, patients who share stories of being misdiagnosed almost always tell me they felt their doctor was not listening or being dismissive. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has a toolkit for engaging patients in diagnostic safety that teaches patients how to succinctly explain their symptoms and history and also has a clinician component, which is 60 seconds of deep and reflective listening.

Dr. Singh: There are a lot of things clinicians can do to build that shared understanding, but this requires some time and effort. When you're running from one patient to the other, and you have 10, 15, 20 minutes with a patient and then you have to do your medical records and all that documentation, other administrative tasks, preauthorizations, inbox messages, it all adds up. We know what the ideal situation looks like, but when you look at actual, real practice, it's really hard to achieve that. It's important to acknowledge that medicine is not just about procedures and tests but also time connecting with and listening to our patients.

Q: What are the most important implications of your results for diagnostic safety?

A: Dr. Giardina: It's building evidence that patients' experiences meaningfully contribute to what we understand about the diagnostic process, and ultimately how to improve that process. Sustaining patient engagement will always be work, but the benefit is reducing errors and with time improving trust. Clinicians are victims of errors too. Patient feedback can provide opportunities to learn and make changes to reduce the risk of future errors. Having patients involved in diagnostic safety only adds to the richness of our understanding.

Dr. Singh: I think all health care organizations should be gathering and using patient-generated data of some type to figure out diagnostic performance. All health care organizations should be looking at their patient complaints for patient safety issues. They're there, often in text form in patient narratives. All those data need to be not just looked at but also used for patient safety improvement.

Q: Is there any advice you'd give physicians in this area?

A: Dr. Singh: We have a very pragmatic resource that we developed recently through AHRQ that basically walks through how clinicians can review their own medical records to see how they are performing and get feedback. Essentially, we want clinicians to get feedback on their diagnostic performance, but it requires a lot of time and effort, and they get a little nervous if, for example, their supervisor comes and talks to them about it. To build some psychological safety around learning from your own experiences and learning from your own cases, we suggest starting with this tool, Calibrate Dx, where you do a little self-assessment on your own cases, maybe with a peer. I might ask another doc, “Hey, can you look at my recent cases that I saw with new cancer diagnoses?” You'd select, say, five cases from your last three months, review those records of those patients and see how you performed, and you have a structured way of looking at your records and evaluating yourself through this tool.

Clinicians can also ask patients for feedback. Engaging patients as a team is really important. That's something that we've talked about a lot, that we need to start considering that diagnosis is not just an individual clinician thing. It's a team-based process, or a team-based phenomenon, where the other team members, including not just health care professionals, but also patients, are part of your diagnostic team. Just like [when] we as a team give feedback to each other, we get better. Patients need to be included in some of those conversations.

Q: Do you have any other take-home points?

A: Dr. Singh: After doing two decades of research in this area, I think there are three traits that are essential for any clinician: listening to patients, humility, and curiosity. Regarding humility, it's important because we have shown the presence of overconfidence when clinicians don't seek help when we most need it. Regarding curiosity, we often need to step back and keep asking questions when the patient brings up a concern that doesn't seem that straightforward. Curiosity is relevant for patients too—many are very curious and are looking things up by putting their symptoms in ChatGPT and asking specific questions. We have to keep up with their curiosity.