Primary care primed for BRCA management

A pathogenic sequence variation in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene occurs in about one in 400 people, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Primary care physicians treating women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations could play a vital role in not only identifying but also managing this risk factor for breast and ovarian cancer.

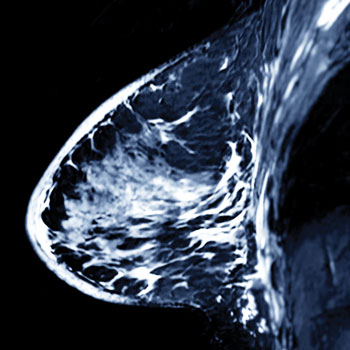

A pathogenic sequence variation in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene occurs in about one in 400 people, according to the National Cancer Institute. These mutations are associated with a 70% lifetime risk of breast cancer and a 20% to 40% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer. Recent studies in JAMA Oncology showed that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can significantly reduce breast cancer mortality in women with a BRCA1 mutation and preventive oophorectomy can significantly reduce all-cause mortality in women with either mutation. But these options can only be considered if a mutation is known.

It's true that some patients may only find out about their genetic mutations after a cancer diagnosis, and by then, many of them are under the care of specialists. But being referred for genetic testing after giving a family history to a primary care physician can be the first step in prevention.

Steven A. Narod, MD, a professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and department of medicine at the University of Toronto in Canada and a senior scientist at Women's College Research Institute, called primary care physicians the gatekeepers of the testing process.

“Take the family histories and give the patients the option of testing,” said Dr. Narod, who was a coauthor on the JAMA Oncology studies. “If they're positive, go out of your way to make sure the daughters and the sisters are being cared for.”

Amy Farkas, MD, MS, FACP, an associate professor of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said this is the ideal role for primary care. “What's really recommended is you talk to all patients, but in this case specifically women, about breast cancer risk,” she said. “Generally, when I'm meeting a patient for the first time, I'm taking a full family history and then every so often checking in and seeing if there have been any changes.” For example, if a patient's sister or aunt has been recently diagnosed with breast cancer, that could be an indicator that the patient should be sent for genetic testing.

Additionally, Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Chicago, said primary care can play a key role in the evolving field of preventive oncology. “We are really hoping that primary care physicians will initiate testing … as a way to get to precision prevention and management of high-risk patients,” she said. “That's really what would drive significant reduction in mortality from chronic diseases.”

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends using an “appropriate” brief familial risk assessment tool to evaluate risk for BRCA-related cancers in patients with a personal or family history of breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer or those whose ancestry is associated with BRCA mutations. Some examples of screening tools are the Ontario Family History Assessment Tool, the Manchester Scoring System, the Referral Screening Tool, the Pedigree Assessment Tool, and the 7-Question Family History Screening Tool. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) as well as the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) also publish guidelines for detecting the mutations and preventing potential complications.

Primary care physicians should rely on these tools when identifying a patient with potential risk factors, Dr. Farkas recommended. She noted that risk assessment is the only way to correctly identify patients who would benefit from genetic testing and preventive surgeries.

“It takes time, and time is always a scarce resource in primary care, but I think it's really important to take the time to talk to patients about what their risk is and what that means in terms of screening,” she said.

Managing anxiety

One of the first challenges an internal medicine physician might face when recommending genetic testing is patient anxiety.

“It's important to remind patients that the majority of breast cancers are not hereditary,” Dr. Farkas said. “I send lots of patients to genetics and very few of them come back positive. I think it's important to also let patients know that regardless of the test result, as their primary care doctor, we're there to guide them on their next steps.”

While many genetic diseases don't have treatments, “when it comes to breast cancer, we are able to do things, whether it's related to a genetic mutation or not, to improve outcomes,” she added, including screening, medications, and surgery. “Remind patients that we're doing this because we have the ability to help.”

Similarly, Dr. Olopade stressed the importance of primary care in managing patient anxiety around cancer. If a patient turns out to have a positive BRCA test, “the next steps really are to reassure the woman that not only can we prevent cancer, but we can also detect it early by using the right screening tool,” she said.

Dr. Narod recommends genetic testing if there is a history of breast or ovarian cancer in any immediate family member, but there are hurdles to overcome, he said. In both the United States and Canada, regulations prevent genetic counselors from contacting relatives directly, so the process depends on the patient reaching out to her sisters and daughters and recommending testing. “They don't always do it,” he said, adding that even if they do, eligible relatives might not want to find out their status or may not have access to testing.

“Also, we tend to be too conservative in who is eligible for testing,” Dr. Narod said. Because of that, patients who don't meet current eligibility criteria would need to pay for these tests out of pocket, and that can pose a substantial barrier to getting them done at all, he noted.

The stakes are somewhat different for a patient who has cancer already compared with one who is healthy, Dr. Narod pointed out. Genetic testing should be done in all patients with breast cancer who are younger than age 65 years and in all patients with ovarian cancer. Finding a BRCA mutation in this population could help with treatment options and can also provide a reason for relatives to go for their own genetic tests, he said, but most of this process is usually led by an oncologist or other specialist.

Options for prevention

Prophylactic mastectomy, oophorectomy, and salpingectomy are potential options for decreasing cancer risk in patients with a BRCA mutation. If a patient is not ready to take these steps, however, routine breast screening with MRI could also be an option. Most guidelines recommend annual MRIs for women with BRCA mutations, and while mammography can also be used in those groups, it is not advised in younger women with BRCA mutations, who tend to have denser breast tissue, according to Dr. Olopade.

“It's really important to talk with the woman about how she's feeling about this” and put that into context, Dr. Farkas said. Specifically, she recommended asking about the patient's reproductive goals and whether breastfeeding is something she might want to do down the line.

Dr. Olopade said she tells women with a BRCA mutation that if they want to have children, they should do it as soon as possible. “When you're done having your child[ren], you may choose to have your ovaries removed. … There will be age-specific interventions, but the risk of ovarian cancer … is not until women are close to menopause, so in the fourth and fifth decade of life. But screening for breast cancer can start immediately,” she said.

Regarding ovarian cancer, “there really is no good screening,” Dr. Farkas said, adding that some clinicians might recommend performing routine transvaginal ultrasound and measuring cancer antigen-125 levels should salpingectomy or oophorectomy not be an option. “We know from large studies that those are ineffective screening modalities, [but] if a woman was choosing not to have surgery, that would probably be the next best option,” she said.

Men can also have BRCA mutations, as well as associated elevated risks of male breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, but their options for prevention are more limited. “There's not a whole lot of breast tissue to remove in a mastectomy for a man and you're not going to remove someone's pancreas,” Dr. Farkas said. “It definitely changes their genetic risk, but we don't necessarily think about it in the same way as we think about it with women.”

Clinical breast exams are possible in men, as is mammography, but strong evidence is lacking as to how these patients should best be screened.

“We don't have any way to screen for breast cancer other than for men to just make sure that they are examining their breasts and then they bring any unusual abnormality in their chest to their doctors,” Dr. Olopade said. “But we don't have any evidence that doing a mammogram or MRI makes a difference for men.”

However, because men can pass the mutation on to their offspring, it is recommended that they speak to sons and daughters as well as siblings about genetic testing, Drs. Farkas and Olopade noted.

With the field constantly changing, Dr. Farkas hopes that technology to screen and treat patients with BRCA mutations will continue to improve and that primary care will be at the forefront of delivering this care.

“I think you're going to see more personalization of screening recommendations to meet an individual's personal risk of breast cancer,” she said.

Until then, Dr. Farkas urged primary care physicians to “take the time to really think about what the individual patient's risk is. It's surprising—if you really talk to patients and get that family history, you can find patients that may actually be at higher risk of breast cancer than you might think.”