In this together

Correcting medical errors in a systematic manner has come a long way, but have we made progress in helping our colleagues and ourselves deal with mistakes?

In a delightful and definitive biography, “William Osler: A Life in Medicine,” Michael Bliss recounts that “Osler's first patient in Baltimore [soon after his recruitment from the University of Pennsylvania to Johns Hopkins in 1889] was an important elderly gentleman, a Hopkins Trustee, perhaps. Osler felt a pelvic tumor, diagnosed it as an inoperable sarcoma, and ‘in as gentle a way as I could, I [Osler] told the patient's wife, and advised that a surgeon see the case. The surgeon came the next day, drained the patient's distended bladder with a catheter, and thus disposed of the ‘tumor.’ Osler related that story often, using it as an object lesson in his teaching.”

I've done the same, as so many of us have; that is, commit an error, and use it as a story later on to illustrate how errors can so easily occur, and how we all commit them—from Dr. Osler to me and you—and how we all struggle to face our mistakes.

It's been a while since I first read “Facing Our Mistakes,” a poignant New England Journal of Medicine Sounding Board piece, authored by David Hilfiker, MD, and published on Jan. 12, 1984. Dr. Hilfiker related the anguish he experienced dealing with a horrible medical error six years earlier, one that resulted in the loss in utero of a healthy fetus. He described his guilt, and pain, and then his anger as he had to, somehow, deal with his mistake without any way to talk this through with colleagues, without being able to seek restitution, absolution, or peace. He had to face his mistake alone.

Processing medical errors has come a long way since then. We understand better how we make diagnostic decisions and the difference between “fast thinking,” that is, clinical reasoning based on “rules of thumb” (heuristics) that enable us to move through our busy schedules, and “slow thinking,” that is, clinical reasoning in which we more deliberately analyze differential causes of a clinical problem, as well as the indicators for when we need to move from one way of thinking to another. We have also come to appreciate flaws in our diagnostic thinking (biases) that partially account for why we so often seem to “get it wrong.”

We recognize, as well, the contextual importance of the systems in which we work, even to the point of regarding most errors as failures of the system, not the individual, and we have encouraged a shift to blame-free culture and systematic reporting of errors, be they near-misses or errors associated with harm. Finally, we have processes for analyzing errors, such as root-cause analyses, fishbone diagrams, or comparable strategies to minimize the chance the error will be repeated.

But have we made progress in helping our colleagues and ourselves deal with mistakes?

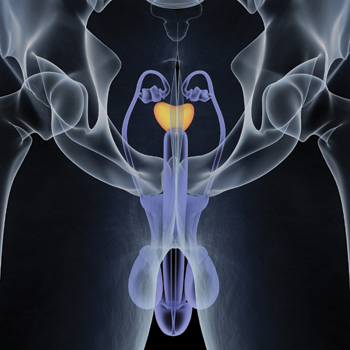

Too bad Bliss tells us nothing about how Osler handled the embarrassment of diagnosing an obstructed bladder (let's assume benign prostatic hyperplasia) as a pelvic sarcoma. I wish we knew more. I'm sure Osler's reputation as the country's best physician did not help matters. We know more about the personal aftermath of Dr. Hilfiker's mistake. Without a sanctioned or even informal process for dealing with his error, he turned his emotions inward. He suffered from what recently has been referred to as the “second victim” syndrome. “Since there has been no permission to address the paradox openly,” he wrote, “I lapse into neurotic behavior to deal with my anxiety and guilt. Little wonder,” he continued, “that physicians are accused of having a God complex; little wonder that we are defensive about our judgments; little wonder that we blame the patient or the previous physician when things go wrong, that we yell at the nurses for their mistakes, that we have such high rates of alcoholism, drug addiction, and suicide.”

This was 40 years ago. How far have we come in addressing not only the systematic quality improvement issues but also the psychological impact associated with medical errors? Having recently committed a medical error myself, I can say progress has been made. If nothing else, I knew how to proceed. I informed the patient and reported the error in our hospital's safety-net electronic reporting system. That was a decidedly neutral experience. I felt neither absolved nor punished, but at least I was able to believe my recording of the error might do some good. What did help much more, though, was to quietly and privately share the details of what happened with trusted colleagues. I refused to allow them to support me with comments such as, “Oh, we all have done something similar to that,” and they were wise enough not to force those ineffective balms upon me. I described what happened, took ownership for the error, and they understood. I was not looking for comfort but this was comforting nonetheless.

ACP has an important role to play in addressing the problem of diagnostic errors and the impact errors have upon physicians, personally. I am proud that the College already is engaged at several levels. We are charter members of the Coalition to Improve Diagnosis, an initiative of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, and we have joined the efforts of the National Academy of Medicine, formerly the Institute of Medicine, to improve patient safety by decreasing errors in diagnosis. Our Education Division has produced an innovative series of cases dealing directly with diagnostic thinking and diagnostic errors. Having read through them recently, I am so impressed with the educational value of this series. The College has turned its attention to safety in the office (where my error occurred) and is working on developing a position paper on the topic.

That still leaves, of course, the issue of how we, as internists, can face our mistakes personally and professionally. That issue will never go away. Regardless of the strides made in improving accuracy of diagnosis and addressing threats to patient safety, errors will still occur. We all know that. ACP's Physician Wellness Task Force has recognized that dealing with mistakes is necessary to improve wellness and resilience. Our strategy is based upon wellness champions who will be reminding us that so much of how we cope with the anguish of errors depends upon the support we receive from each other. Reflecting on my personal experience, I appreciated the importance of colleagues and being able to share things with coworkers I could trust. Trusted relationships can extend beyond one's office. Fellow ACP members can play an important role here. Forums on ACPOnline.org, which are accessible to members, can be used for similar purposes, as can time together at meetings. We must never forget we are all in this together.

It is a pleasure and honor serving as your President, and sharing my thoughts with you. Please let me hear from you.