Current challenges in prescribing generics

The price of some generic drug classes has skyrocketed in the past year, making this once simple option more difficult to offer to patients.

Prescribing generic medications should be a simple way to meet patients' health care needs without costing them, or the system, a lot of money.

However, recent news stories and research studies have shown generic use to be a little less universally cheap and easy than expected. The price of certain generic drugs has skyrocketed in the past year or so. Also, since the Affordable Care Act, some health plans have placed generic drugs for expensive chronic conditions in higher-cost tiers. And finally, a few research studies have shown room for improvement in physicians' prescribing of generics and patients' adherence to them.

Resolving the pricing issues will fall to the government, but internists may need to consider these various developments when dispensing prescriptions and advice to patients. And doctors should take the lead in efforts to make sure that generics are prescribed and taken as much as possible, experts said.

They offered some explanations and solutions for all of these recent challenges to effective prescription of low-cost generic medications.

Price spikes

The price spikes have been the most noteworthy of the issues affecting generics, attracting media attention and a Senate hearing on the subject last November.

But those on the front lines had noticed the problem long before. “Over a year ago, we started getting calls from our members—independent pharmacy owners—over how many commonly used generic drugs had been virtually overnight spiking in price by many percentage points—100%, 300%, 1,000%,” said Ronna B. Hauser, PharmD, vice president of policy and regulatory affairs for the National Community Pharmacists Association.

The majority of pharmacists have seen multiple significant price increases affect the generic drugs they dispense, according to survey by the association released in December 2013. Digoxin, doxycycline, haloperidol, levothyroxine, morphine, and pravastatin were among the drugs most commonly cited as issues by the pharmacists.

Albendazole is a drug that shows the extremity of price shifts, according to Aaron Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston who testified at the Senate hearing. He told the Senate that “between late 2010 and 2013, the listed average wholesale price for U.S. patients rose from about $6 to over $119 per typical daily dose” for the drug.

As a result, patients may pay more out of pocket for drugs or not get them at all if they or, in some cases, their pharmacies can't deal with the increased prices, Ms. Hauser noted.

The cause of the spikes comes down to lack of competition, “which can vanish for a number of reasons, including business decisions by manufacturers, fluctuations in the supply and demand of the market, anticompetitive behavior, and reassertion of patent or market exclusivity rights,” Dr. Kesselheim told the Senate.

These issues are a natural outgrowth of an uncontrolled pharmaceutical market, according to Zaheer Ud Din Babar, PhD, head of pharmacy practice at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. “The majority of the countries around the world control prices, because they think [medication] is an essential commodity,” he said. “Having competition—market forces and things—sometimes it's effective and sometimes it's not.”

To correct for these failures of the market and ensure affordable access to medications, Dr. Kesselheim recommended to the Senate committee some possible interventions by government agencies. The FDA could facilitate the development of competitor drugs and the Federal Trade Commission could investigate anticompetitive behavior, for example.

Talk to pharmacists

Until such solutions are implemented, internists can reduce the risk of price spikes causing medication nonadherence by having an open line of communication with their local pharmacists, who may be able to suggest alternative medications or other solutions.

“[Doctors] are not going to know when they're prescribing which products have these price spikes, and that's why communication with the pharmacists becomes even more important,” said Ms. Hauser.

Clinician awareness and government intervention are the main solutions to the problem of generic medications in high-cost tiers, too.

This issue was brought to light by advocates for patients with HIV. The AIDS Institute in Florida reviewed the health plans available in the Florida marketplace and found 4 that put all HIV medications in their highest-cost tiers.

“It was really shocking, because it was even the generic versions of those drugs. Generic drugs are usually Tier 1 or maybe Tier 2, but they were all in Tier 5,” said Wayne Turner, JD, a staff attorney at the National Health Law Program, a nonprofit legal organization based in Washington, D.C.

Other states and diseases have shown similar patterns. “We've been hearing that all over the country and not just on HIV drugs, but on medications affecting other conditions, too. We talked to folks from the multiple sclerosis society, people in the cancer community,” said Mr. Turner.

In response, his organization filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and some of the insurers with problematic plans have agreed with the state of Florida to restructure their drug benefits in 2015 plans.

But until the issue is definitively resolved, chronic disease patients need to keep a close eye on their insurance policies' drug coverage. “Our real concern is that we would see this race to the bottom. All of the plans would start putting their medications in the highest-cost tiers,” said Mr. Turner.

Default choices

There's not much physicians can do to remedy the cost problems facing certain generic drugs, but they are ideally positioned to tackle another issue: making sure that generics are prescribed whenever possible. A recent study found that a relatively simple change could significantly increase the percentage of prescriptions that were generic rather than brand-name.

The research was conducted at 2 outpatient internal medicine clinics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, which knew their generic use was less than maximal.

“They had tried educational interventions, with letting physicians in their clinic know about the pros and cons of brands versus generics. They were receiving financial incentives from insurers to reduce the rates of brand-name medication. A lot of those things weren't working,” said lead study author Mitesh Patel, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and health care management at the University of Pennsylvania.

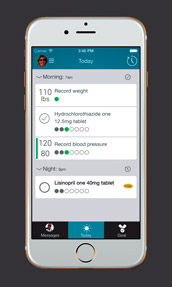

Their simple solution was to change the default setting in the electronic medical record, so that prescribing clinicians would see their generic medication choices first, instead of generics and brand-names together.

After the change, internists significantly increased their use of generic beta-blockers and statins compared to 2 family medicine clinics that served as controls. The use of generic proton-pump inhibitors also went up, but not significantly, according to results published in the Nov. 18, 2014, Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The results were similar to what we expected. Defaults are a very powerful way to change behavior,” said Dr. Patel.

The findings suggest that physicians hadn't been deliberately choosing the brand-names but may have been using them because it was faster or more convenient. “Brand-name medications are often easier to remember and type in—Coreg versus carvedilol or metoprolol versus Toprol,” said Dr. Patel.

The study also found that residents were more likely than their attendings to prescribe generics, even before the change was implemented. Dr. Patel offered a couple of possible explanations.

“In medical school, you're typically taught the generic names of medications. When I was a resident, I didn't even know a lot of the brand-name medications until I met with patients and they told me what medicines they were on,” he said.

Attendings also often have more of a history with the brand-name drugs in the sense that they used to meet the sales reps and that they used the drugs before generic alternatives were available. “Lipitor was a brand-name medication until near the end of 2011, and so attendings were used to prescribing Lipitor, whereas residents who started in 2012 had both [generic and brand-name versions] available to them,” said Dr. Patel.

When a generic becomes newly available, it makes sense to switch chronic prescriptions over from the brand name, but it requires time for conversation with patients. Dr. Patel suggested asking, “There's a generic medication that's come out with the same effectiveness but maybe lower cost for you. Would you like to switch?”

In many places, the pharmacist will raise that issue with the patient, but it's better for it to happen during the medical visit, according to Dr. Patel. If a switch is suggested in the pharmacy, “the patient may be thinking, ‘My physician prescribed a brand name. Is there a difference? I'm not sure,’” he said.

It may also be helpful to talk about the appearance of the medication during the conversation about switching and how it can vary from brand name to generic or among generics. A recent study found that when a post-myocardial infarction patient's pill changed shape, it increased the risk that he would stop taking the medication by 66%. A change in color increased nonadherence by 34%, according to results published in the July 15, 2014, Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Physicians should help make their patients aware that generics can change appearance without changing their potency,” said Dr. Kesselheim, who was the lead author of the study.

Patient education about this issue, and generics generally, could even be printed, suggested Dr. Babar. “The best thing to increase patient adherence is to provide them leaflets. They have been found effective,” he said.

To change physician behavior, however, the best solutions may be invisible and inexpensive, like the default setting in Dr. Patel's study. “There were no educational sessions, no incentive designs ... no pop-up alerts, no training,” he said.

That lesson could be used to improve generic prescribing in other facilities, or for entirely different challenges. “As more and more physicians start using electronic health records, more and more of the decisions get shifted to the design in the electronic health record, and there's a lot of room for improvement there,” said Dr. Patel.