Psoriasis symptoms can be tough to address

A recent survey showed that many psoriasis patients are not satisfied with their care, reporting inadequate relief from such symptoms as itching and scaling. Learn more about clues to diagnosis and suggestions on treating and managing symptoms of both mild and more severe disease.

Numerous patients with psoriasis, an autoimmune disease with medical risks that extend more than skin deep, report that their itching, scaling and other miseries haven't been adequately eased, according to recent survey data.

Overall, 52.3% of psoriasis patients were dissatisfied with their care, according to an analysis of surveys conducted from 2003 through 2011 by the National Psoriasis Foundation and published in the October 2013 JAMA Dermatology. Among those patients coping with severe disease, impacting more than 10% of their skin's surface, 42.5% reported inadequate relief.

If anything, those findings only capture the surface of patients' discontent, said Florida-based dermatologist Neil Alan Fenske, MD, FACP, noting that the surveys likely reach a relatively health-savvy group.

“I think the bottom of the pyramid is much greater than what was even represented in the paper, based on my own clinical experience,” said Dr. Fenske, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa.

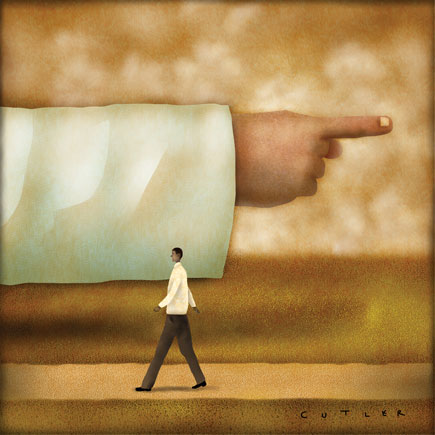

Some contributing factors, according to Dr. Fenske and other physicians interviewed, include the ongoing shortage of dermatologists, the risk of missing skin problems during a time-pressed checkup, and the tendency of patients to suffer in silence. Either they don't point out the reddened skin patches in the first place or think that minimal symptom relief is all they can expect. Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, associate professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, emphasized that “Psoriasis is a lifelong disease. Patients may have tried topicals [medications], and it keeps coming back, and they just sort of give up. Or they may have a hard time finding a physician who is knowledgeable about using the therapies that are necessary.”

Dr. Gelfand has played a key role in some of the recent studies indicating that the skin disease, which impacts about 2.2% of Americans according to the National Psoriasis Foundation, also can be associated with other medical conditions. One study he authored, also published in the October 2013 JAMA Dermatology, found that the severity of psoriasis correlates with a heightened risk of other medical conditions, including diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, heart attack and peripheral vascular disease.

Another study, published in November 2013 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, reinforced the ever-present possibility of missing related arthritis. When rheumatologists were asked to evaluate 949 patients with psoriasis, 30% were found to have psoriatic arthritis, and of these, 41% had never been previously diagnosed.

Diagnostic differences

The autoimmune disease, triggered by an overproduction of T cells and the resulting accumulation of skin cells, falls into 5 primary types: plaque psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris), guttate psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis. While it can be diagnosed in children, it's far more common in adults.

Some common locations include the elbows, knees or scalp, although symptoms can flare pretty much anywhere in the body, including the fingernails and inside the mouth. Frequently, the patches of thickened reddish skin can itch or feel sore. Whereas rashes with other skin conditions tend to be less well defined, those with psoriasis develop sharper edges, Dr. Gelfand said.

If psoriasis is found in one area, such as the elbow, it tends to show up on the opposite elbow, he said. He noted that another hallmark is the silvery appearance of the scales.

Some psoriasis can be mistaken for eczema, Dr. Fenske said. But the rash associated with eczema is the result of excessive scratching from the dry, sensitive skin involved. “Eczema is generally the itch that rashes,” he said. So if the patient isn't reporting a need to scratch, the source is not eczema or contact dermatitis, he said. Psoriasis patients may or may not itch, he said.

Another challenge is that psoriasis might emerge in locations, such as the genital area or skin folds under the arms or beneath the breasts, that a patient may be too shy to point out, physicians said. A family history of psoriasis or other associated conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, might provide diagnostic clues, Dr. Fenske said. But even if the symptoms appear to be classic, he recommends conducting a skin biopsy just to be sure.

Conversely, if the patient reports any arthritis-type symptoms, the primary care doctor should backtrack and look for any psoriasis, said Bernard Rubin, DO, FACP, division head of rheumatology at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

For example, there may be psoriasis in the patient's nails that initially looks more like a fungal infection until it's tested, Dr. Rubin said. One hallmark of psoriatic versus rheumatoid arthritis is when the joint closest to the tips of the fingers or toes is inflamed, along with the other 2, he said. “Instead of tapering down at the end, it makes it look kind of bulbous. So it looks like a link sausage,” he said.

And don't assume that relatively mild psoriasis translates to limited arthritis, Dr. Rubin said: “The amount of psoriasis you have on your body does not correlate with how severe the arthritis is.”

Treating milder symptoms

While psoriasis is categorized into 3 categories of severity, based on the percentage of the skin affected, even patients with relatively few reddish patches might require more aggressive treatment, Dr. Gelfand said. Doctors should not assume anything about the disease's burden without talking to the patient, he said.

He recommended asking, “‘How much does the disease impact your physical well-being? Is the itching from the disease impairing your sleep, impairing your ability to use your hands or your feet? How much anxiety, depression, social isolation or embarrassment is this causing you?’”

Many of Dr. Gelfand's patients tell him that they've never been asked such questions before. “People cry in my office regularly when considering the impact the disease is having on their lives,” he said.

Overall, 82% of patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis describe the diseases as eroding their enjoyment of life, according to a December 2012 study in the journal PLoS One, based on the same psoriasis foundation survey data from 2003 through 2011. Among the feelings they described are anger (89%), helplessness (87%), embarrassment (87%) and self-consciousness (89%).

For milder cases, treatment with a topical steroid like hydrocortisone 2.5% is a good first step, said Henry W. Lim, MD, chairman and C.S. Livingood Chair in the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. But primary care doctors should incorporate treatment breaks to guard against any adverse corticosteroid effects, such as thinning of the skin, he said. For example, the patient could apply the ointment for 2 to 3 weeks, and then stop for 2 to 3 weeks before beginning again.

In vulnerable areas, such as along the skin folds in the groin area, the buttocks or under the breasts, it's particularly important that the mildest prescription class of topical steroids be used, as the skin is already thin in those areas, Dr. Lim said. Two nonsteroidal alternatives are tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream, but those medications are usually only prescribed after topical steroids, as they are expensive and it can be difficult to get insurance approval, he said.

Those topical medications should be followed with a checkup to gauge effectiveness, Dr. Lim said. “If the patient is in good compliance and using them and still the condition does not clear in 2 to 3 months, then it would be best to refer them to a dermatologist,” he said.

It may be that the condition is not caused by psoriasis, said Dr. Lim, describing a recent referral case that turned out to be ringworm. Or, if the patient isn't getting sufficient relief, the next step likely would be phototherapy, which is typically handled by a dermatologist, he said.

More severe symptoms

When referring, the primary care doctor should verify that the dermatologist handles medical issues (rather than just cosmetic), including psoriasis, Dr. Fenske said. Phototherapy is not routinely provided, even by dermatologists, as it's time-intensive and has limited reimbursement, he noted, although he offers it and describes it as a great next step before trying systemic medications and biologics. “This is the safest, most cost-effective way to treat extensive psoriasis, without a doubt,” he said.

Among oral systemic medications, methotrexate is prescribed more frequently than acitretin or cyclosporine, with 14.5% using the drug by 2011, according to treatment survey findings in the 2013 JAMA Dermatology analysis. A handful of biologics have been approved in recent years for psoriasis. Based on the analysis, etanercept (Enbrel) and adalimumab (Humira) are most commonly prescribed. From 2005 to 2011, between 11.3% and 19.8% of patients were taking etanercept; the use of adalimumab had reached 12.4% by 2011.

Several of the physicians interviewed said that primary care doctors are typically more comfortable referring out once they feel a patient might benefit from a biologic drug for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis symptoms. But Dr. Fenske, who teaches an annual course “Derm for the Non-Derm” in Key West, Fla., every year, believes that any primary care doctor who is comfortable caring for an adult with type 1 diabetes should also be able to manage a psoriasis patient on biologic drugs, particularly with some education and support from a dermatologist. For example, the patient could be referred to a dermatologist to confirm the initial diagnosis and then for annual visits, with the family doctor managing in between, he said.

Before starting a patient on a biologic drug, Dr. Fenske said, closely screen for any contraindications, including testing for tuberculosis and checking that the patient doesn't have another condition, such as heart failure or multiple sclerosis that could be worsened by therapy. It's also important to stress to patients that they must stop the drug immediately and call the doctor's office if they develop any sort of cold or flu-like symptoms, he said.

In his own practice, Dr. Fenske typically asks the patient to return to the office every week or so for the first several months. Once the patient appears to tolerate the drug well and is educated, the frequency of those checkups might stretch to every month and then every 3 months, but no less frequently than that, he said.

One caution he passes along to physician colleagues: Be sure that the specialty pharmacy is complying with the stated time frame on the prescription. Dr. Fenske said he's experienced situations in which he wrote a 1-month prescription but learned later that the pharmacy kept mailing the drug, and thus the patient didn't have to come in for checkups and monitoring.

For doctors more comfortable with referring a patient out, Dr. Fenske suggests following up to check that the patient is satisfied with the care. Inadequately treated psoriasis can trigger a cascade of unhealthy coping behaviors that will reverberate back in the primary care doctor's office, he said.

“When you look at yourself and you feel bad about yourself, you don't exercise as much, and you start to overeat,” he said. “Then that makes you prone to the metabolic syndrome, which you're already prone to. And then your quality of life goes down, and you become socially withdrawn.”