Look for reasons if patients refuse advice

Refusal can be frustrating for physicians, who likely see their medical advice as contributing toward healing and improving quality of life. But patients reserve the right to make informed decisions about their care, even if these decisions run counter to what's been recommended.

Internists will inevitably encounter patients who refuse recommended screening and treatment, whether it's declining to obtain a flu shot or choosing not to take medication for a chronic disease such as diabetes or hypertension. Refusal can be frustrating for physicians, who likely see their medical advice as contributing toward healing the sick and improving the quality of their patients' lives.

But patients reserve the right to make informed decisions about their care, even if what they ultimately decide to do, or not do, runs counter to medical advice. ACP's Ethics Manual, Sixth Edition, clearly states 3 pillars of informed decision-making, the third of which is that decisions made by patients or their surrogates must be voluntary and uncoerced.

“Basically, informed refusal is the flipside of informed consent, where it's the right of any adult who has decision-making capacity to refuse any kind of medical intervention, even if the physician thinks it's a bad decision,” said Michael J. Green, MD, MS, FACP, professor in the departments of humanities and medicine at Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey, Pa. “It's about respecting patient autonomy.”

What is ‘informed’?

Providing information in the course of shared decision making amounts to offering alternatives, said Don S. Dizon, MD, FACP, director of the Oncology Sexual Health Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“My job as a physician is not to give patients a roadmap of what I would choose for them, but to give them several routes, outline the risks and benefits of each, and provide my 2 cents,” Dr. Dizon said. “Then the patient can give me a sense of her goals, values and preferences that I can put into context. How does the information I am providing fit with what is important to her?”

Laying out all the options can also help the physician reframe the discussion for himself or herself, said Paul S. Mueller, MD, FACP, chair of the department of general internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a past member of ACP's Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. “There's a whole list of options for low-grade prostate cancer, including prostatectomy, hormonal treatments, radiation and watchful waiting. If a patient says that, after putting it all together, he wants to do radiation, he's not refusing surgery as much as he's accepting radiation.”

Dr. Green notes the power of a second, or even third, opinion. “I encourage patients to consult with other physicians, and tell them that maybe someone else can help clarify the issue better than I can,” he said.

Assessing capacity

ACP's Ethics Manual notes that decision-making capacity should be evaluated for a particular decision at a particular point in time and notes that a patient may be able to express a particular goal or wish but not have the ability to make more complex decisions. In other words, the patient may wish to receive care and get well but not be able to weigh the risks and benefits of one treatment against those of another.

“Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals,” by Thomas Grisso, PhD, and Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, lays out 4 scenarios that should prompt physicians to be extra cautious in assessing decision-making. These are when patients:

- have an abrupt change in mental status,

- refuse recommended treatment, especially if they are do not want to discuss why,

- consent to particularly risky treatments without careful consideration of the risks and benefits, or

- have known risk factors for impaired decision-making, including neurological conditions, cultural or language barriers, and advancing age.

Age-related cognitive impairment can be particularly challenging. According to a study published in the July 27, 2011, Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the overall prevalence of incapacity among healthy elderly patients is 2.8%, signifying a need for assessment, yet the study also revealed that physicians identify incapacity in just 42% of affected patients.

“You have to be careful with the nuances of these situations, as people change over time,” said Davoren A. Chick, MD, FACP, clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “There are gray zones where it becomes more difficult to have the conversation. There may be cases where the patient has borderline decision-making capacity or early dementia but is not really at a stage where they have lost the ability to decide.”

The JAMA study compared several tools for assessing capacity, including the Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE), the Hopkins Competency Assessment Test, and the Understanding Treatment Disclosure, and suggests that the ACE, which is backed by a large clinical trial, may be the most practical for physicians to use. The ACE, which is online, contains questions and a scoring system to determine capacity when the patient faces a medical decision.

Voluntary refusal

It is an unfortunate reality that patients are sometimes convinced to make decisions counter to their own desires and that sometimes the “convincing” becomes coercive.

“There is coercion in all sorts of settings. Sometimes there are time or financial burdens associated with the treatment so that someone else is telling the patient to say no,” said Dr. Mueller. “Maybe the patient is also caring for someone at home. Maybe the treatment is expensive and a spouse says the couple can't afford it. Those are rational motives for a patient, but it should be the patient's decision, not a third party's.”

Dr. Dizon pointed to certain cultural values as a source of coercion. “In some cultures, it's not what a woman wants, but what her husband wants. Bring the husband in and include him in the discussion if the woman will allow it, but make sure that the decision is being made according to her values and preferences.”

When in doubt, physicians should take a step back and get input and validation, said Dr. Chick. “There is plenty of time to get outside support for your role. Check with your state medical board, look for precedents [in the literature], and review ethics guidelines. It's not necessary to pressure a patient or yourself to make a decision about something you feel uncomfortable about.”

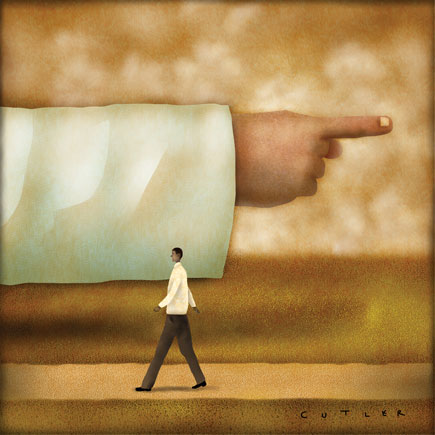

Physicians themselves can be guilty of coercion by offering only one option for care, taking a paternalistic approach to the patient, or threatening to dismiss a patient from a practice if the patient does not comply with recommendations. Such interactions may leave a patient feeling like treatment is an either/or proposition when in reality, it is anything but, said Dr. Green.

“If a physician says he or she is only willing to write a prescription for one specific type of medication, the patient may very well turn around and say he or she will not take anything at all,” Dr. Green said. “Pragmatic physicians compromise and negotiate. Maybe the patient won't choose the medication you prefer but will choose another instead. Remember that second best tends to be better than nothing.”

A respectful attitude is crucial to ensuring that a physician does not inadvertently turn a patient off to treatment or medical care in general, said Dr. Dizon.

“Patients don't want to feel like they are being foolish. Even if their concerns don't seem important to you, those concerns are important to them, so don't trivialize what they are saying,” Dr. Dizon said. “There have been times when I've thought a patient was making an incredibly bad mistake. In situations like that I encourage them to go home and think about it. I want to make sure they are comfortable with the decisions they made.”

Threatening to dismiss a patient because he or she won't comply is unacceptable, said Dr. Mueller. “Never abandon a patient because the patient refused treatment. Refusal is not something you should take personally,” he said. “The patient's reasons most likely have nothing to do with you. Ultimately our goal is to serve the needs of the patient in a way that is consistent with their values and goals.”

Don't stop at ‘no’

Although patients have the right to refuse screenings and treatments, the experts agree that a simple “no” should not be the end of the discussion.

“The most important thing is that if a patient refuses something, that doesn't mean you're done and the conversation is over. You need to understand the reasons why,” said David Magnus, PhD, Thomas A. Riffin Professor in Medicine and Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif. “Find out how they came to believe as they do.”

This goes back to making sure patients truly understand the options that have been explained to them, Dr. Magnus added.

“You need to rule out misunderstandings,” he said. “It's incredibly common for there to be miscommunication. Once you're sure the patient understands all the options and the implications of his or her decision, from there you can negotiate to meet the patient's needs as best you can, given the constraints placed by the patient.”

Dr. Green noted that often it's not the treatment or screening patients take issue with, but the prospect of side effects, pain, or an impact on their livelihood or lifestyle.

“It's not really refusing the intervention, but something associated with it. Recognize that not everyone values the same things equally,” he said. “You as a physician might be concerned with one specific thing in a patient's case [like minimizing risk or treating a particular disease], but that may be just one of 10 things that are important to the patient.”

He added that irrational fears can compound an issue. “That's where it gets dicey. Then the physician's responsibility is to help that patient address that fear. If a patient says she's deathly afraid of feeling nauseated [from a drug], explain that there are ways of avoiding nausea.”

Primary care physicians are in an excellent position to build a case for treatment, not only because they have ready access to a patient's entire medical history and can tailor recommendations with that history in mind but also because having a long-term relationship with a patient allows them get to know the patient as an individual, the experts said.

“It's important to remember that our profession is engaged in supporting a patient's life journey, not just a specific medical event. Each patient has different perceptions and prior experiences, both good and bad, and exploring them helps you to get to know what's important to the patient,” said Dr. Chick. “You have the opportunity to get down to the fundamental desires of that patient, and make sure their choices are congruent with their own value system.”

To illustrate, Dr. Chick noted a patient who arrived at an appointment extremely hypertensive but who did not like the idea of taking a blood pressure medication. The patient was proud of being able to live independently and make her own decisions, so Dr. Chick couched the need for treatment in terms that appealed to the patient's values.

“I explained that my concern was that if she did not take her medication and she had a stroke, that could impair her ability to function and remain independent, which could also compromise her ability to call her own shots,” she said.

Ultimately, the goal is for both patient and physician to feel comfortable in the knowledge that the decision was made after the appropriate due diligence and consideration, but there is one caveat, said Dr. Magnus.

“Sometimes it's up to the state,” he said. “For example, with things like tuberculosis, public health officials are authorized to incarcerate certain individuals as a matter of public health. You don't need informed consent for something that is required by law.”

Documentation

The experts agree that when patients refuse screening or treatment, detailed notes are a must.

“Spell it out,” said Dr. Mueller. “You met with Mrs. Jones. You indicated that a statin would be appropriate and offered it to her. She refused, and her reason for refusal is that she'd rather take a dietary approach.”

Overall, the procedure for documenting informed refusal can be similar to documenting informed consent, depending on state laws.

“There are standard protocols for recording that you have gone over the options with the patient and explained the risks of not undergoing treatment or screening,” said Dr. Dizon. He added that documentation is not only for legal protection, so that there is a written record of the patient receiving and understanding the information, but for the physician's peace of mind, as well.

“By aiming to understand the rationale behind a decision, you can feel more assured that you did your best to present the options in a balanced way,” he said. “There are not a lot of absolutes in medicine. Sometimes we as physicians need to admit that to ourselves.”