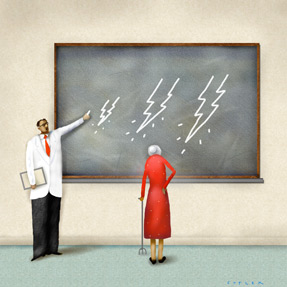

Take time to ease the pain of elderly patients

Assessing and managing pain can be complicated in elderly patients. Learn which tools work, which tools don't, and how to optimize treatment.

As a professor of anesthesiology and pharmacology, Alan D. Kaye, MD, PhD, brought a lot of expertise to his 75-year-old mother's follow-up visit with a pain specialist. But he, and she, still ran into one of the common challenges of geriatric pain assessment when his mother was asked to rate her pain from zero to 10.

When Dr. Kaye's mother couldn't use the scale to indicate that her pain had decreased, the pain specialist balked at doing more nerve-burning procedures. But “It's been shown in many studies, [elderly patients] don't do well with a 10-point scale,” Dr. Kaye said. “They're not good at it.”

Dr. Kaye, who teaches and practices at Louisiana State University and Tulane University in New Orleans, eventually got the specialist to understand that the procedures had in fact successfully reduced his mother's back pain. “We spent an hour ... and I was barely able to bridge the gap. What does someone do who does not have [similar] ability to speak to the health care team?” he said.

Many internists are struggling to answer his question as they treat a growing population of geriatric patients with pain problems. Not only do the elderly have difficulty communicating about their pain, but their comorbidities, frailty and functional limitations also combine to complicate diagnosis and treatment.

When these challenges aren't overcome, the consequences are significant.

“It is very clear that patients with uncontrolled pain certainly have slower rehabilitation, increased health care utilization ... There's a good strong relationship between pain intensity and pain distress and functional impairment and dependency,” said Bruce Ferrell, MD, FACP, during the session “Management of Persistent Pain in the Elderly” at Internal Medicine 2013 in April.

The upside is that a physician who avoids the common pitfalls and successfully treats an elderly patient's pain can make a dramatic difference in that patient's life. Geriatric and pain experts offered advice on how to achieve that feat.

Ask the right questions

The first step, of course, is assessment. As Dr. Kaye found, the usual “zero to 10” scale doesn't work well for a lot of elderly patients. The sad-to-happy face scale can also be difficult for them.

Although sight, hearing and cognitive impairments add barriers, the scales can be problematic even for elderly patients without any of these problems.

“These patients grew up at a time where they weren't exposed to graphic representations of things. The only thing they knew was either a rain gauge or a thermometer,” said Dr. Ferrell, who is a professor of clinical medicine and geriatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Providing a broader scale can be helpful, according to Kenneth E. Schmader, MD, FACP, a professor of medicine and chief of geriatrics at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “Sometimes people do better with a larger scale than the one to 10. You can do these things in combination, where you tell people, ‘Here's the visual analog scale: 100 is as bad as it can be and zero is no pain at all. Where would you put yourself in there?’” he said.

Conversely, fewer rating choices may be easier, too. “Is it mild, moderate, severe?” suggested Dr. Schmader.

The Functional Pain Scale is another assessment option: five yes or no questions that focus on the impact of pain on patients' activities. It's researched and recommended by F. Michael Gloth, MD, FACP, associate professor of geriatrics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“It was developed and standardized in a frail, older adult population. It outperformed the zero to 10 scale as well as three of the most popular pain scales being used. It is far more responsive to changes in pain and does really well for older adults even with dementia,” he said.

When questioning patients further about their pain, yes or no questions are preferred, Dr. Ferrell said. He also recommended repeating yourself to validate their answers.

“Early in the interview, you might say, ‘Do you have pain that's continuous, that's there all the time?’ And later you might say, ‘Do you have periods of time where you don't have pain?’ Those should be validating questions,” he said.

This questioning may be time-consuming. “You have to give these patients time to consider it,” said Dr. Ferrell. “About the time I'm ready to turn and walk away, they give the answer.”

Challenges and pitfalls

Try to have patience when patients don't provide the expected answers, Dr. Ferrell said.

“When I see a patient that says it's a 14 on a 10 scale, I know this patient is very distressed,” he said. “What we're asking them is the intensity. What the patients are responding with is how distressing the pain is.”

It may be tempting in such cases to turn to imaging for answers, but that can be a mistake, according to Dr. Gloth. “You get some back pain and you decide, ‘I'm going to get an X-ray of the back.’ You might as well not even get that X-ray, because you know there are going to be degenerative changes in that older spine,” he said. “Pain issues in older adults are likely to have multiple etiologies.”

Difficult as it may be, questioning is actually the best tool you have. “There are no biologic markers for pain, no objective diagnostic markers,” said Dr. Ferrell. “The most reliable method is simply the patient's self-report. You have to believe patients most of the time.”

Even cognitively impaired patients can generally be believed, he added. “It turns out they're fairly reliable reporters if they're in pain at the moment.”

Caregivers can also provide helpful reporting, a reason to encourage them to come to appointments. “That can cut through communication problems as well as describe the behavioral consequences of the person's pain: if they're up at night, if there's ambulation or functional impairment, if there are environmental risks in the home,” said Perry Fine, MD, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Once a physician has gathered information about the patient's pain, it's time to provide some in return.

“It's extraordinarily important to set the patient's expectations,” said Dr. Schmader, who specializes in treating postherpetic neuralgia. “They will be coming to the doctor expecting that they're going to get a pill that will just take the pain away. I try to educate the patient about what's going on in their body, and that it's unlikely we can find one simple intervention that will take all their pain away.”

“Of all nondrug strategies, the most important thing you can do is family and caregiver education,” agreed Dr. Ferrell.

Patients should understand the treatment strategy—a long-acting drug combined with a short-acting one for breakthrough pain, for example—and the goals. Dr. Schmader offered an example of the latter: “Mrs. Smith, you have severe pain. Let's see if we can get you down to moderate or mild pain and have you function better.”

Choosing a treatment

Achieving pain-reduction goals with treatment requires a slow, individualized, multidisciplinary and multifaceted approach, the experts said. “‘One size fits all’ doesn't work a whole lot,” said Dr. Schmader.

“The main thing is not to get frustrated,” advised Dr. Fine.

Generally, treatment can follow the World Health Organization's three-step ladder for pain management (ascending from nonopioid treatments to strong opioids), according to Dr. Ferrell. “You simply match the intensity of the pain with the potency of the analgesic,” he said.

There are a lot of caveats complicating this simple system in older patients, however. Their higher incidence of comorbidities leads to an increased risk that pain medications will interact with other conditions and other medications.

In addition to expected interactions and side effects, older bodies can respond differently to medications, due to reductions in muscle mass, renal clearance or other factors. The result can be that a drug does the reverse of what's intended.

“Sometimes when you give them a little bit of [haloperidol], they get akathisia and they get worse restlessness and more irritable and more agitated,” said Dr. Ferrell.

Many other geriatric patients, including Dr. Kaye's mother, are treated too far in the opposite direction.

“We radically adjusted her medications a couple of years ago, because she was having some of those classic side effects—sedation and confusion,” Dr. Kaye said. “People might be sedated but they may not be effectively treated for their pain ... If you're not in tune with that, you have a potential to do a disservice.”

In general, finding a treatment that helps elderly pain patients without hurting them is tricky. “Pain increases fall risk. Certain medications you use for pain will increase their risk for falls. You really find yourself in a quandary sometimes,” said Dr. Gloth.

One possible exit from the quandary is nondrug treatment of pain. “The safest things are topical agents. Even heating and cooling, people sometimes find those very useful. It may forestall the need to use other analgesics,” said Dr. Fine. Massage, physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and even acupuncture can be helpful, depending on the problem and the patient.

“Some people start rolling their eyes when you begin mentioning cognitive behavioral therapy and biofeedback and heat and massage and ice. They want the opioid. Others are quite receptive. If they say, ‘Acupuncture helped me,’ that's fine, even though it's not an evidence-based therapy for postherpetic neuralgia,” said Dr. Schmader.

Dr. Ferrell also recommended keeping an open mind toward alternative therapies. “I try not to leave people with no hope. I try to keep them away from things that could harm them. I don't try to spend all my time trying to debunk health quackery,” he said.

Drugs

Of the tried-and-true drug therapies, acetaminophen should be your first line of attack, the experts said. “I'm surprised by how well [it] works in frail, 90-year-old people. A little bit may be all that they need. The risk of giving them NSAIDs [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] is so much higher,” said Dr. Ferrell.

“The biggest risk we face with acetaminophen is it's so readily available we have to be very cautious about counseling people on how much to use,” said Dr. Fine. Make patients aware of the many over-the-counter products that contain acetaminophen, he advised.

Wide availability is both an advantage and a problem with the next type of pain treatment, NSAIDs. “People think that they're safe because you can get a large container at Costco for almost nothing,” said Dr. Fine.

NSAIDs are best considered for acute or episodic pain, the experts said. According to Dr. Ferrell, a few should definitely be avoided in the elderly: indomethacin, ketorolac and oral diclofenac.

Also on Dr. Ferrell's list of drugs to be avoided (in the opioid category) are meperidine, mixed agonists and antagonists and combination drugs that include naltrexone, naloxone or suboxone. The combo drugs were developed to reduce the risk of drug diversion, but the result is that they have a narrow therapeutic window.

“There's very little diversion going on with 85-year-olds in a nursing home,” noted Dr. Gloth, who said that regulatory obstacles present a challenge to prescribing opioids, especially in nursing homes.

The FDA is particularly focused right now on methadone, due to an increase in accidental overdoses. “If you have a patient on high doses of opioids and you want to switch them to methadone, look it up. It's tricky,” said Dr. Ferrell.

Also exercise care with the fentanyl patch, which shouldn't be used in opioid-naïve patients and has a very long half-life because the drug is stored in the skin even after the patch is removed. “If you notice the patient getting dopey or drowsy, and you pull off the patch, it's too late,” said Dr. Ferrell. “I don't use this drug except in patients who can't swallow.”

In general, opioids should be “the last resort for dealing with chronic pain,” said Dr. Fine, although he uses them “in well-selected patients, monitored carefully, starting low and going slow, and anticipating and preventing some of the predictable adverse events, such as constipation.”

Many of the same caveats apply to use of anticonvulsants, like gabapentin. “Their benefits can be appreciable in well-selected patients. There are a lot of patients who unfortunately don't respond, and unless we titrate very slowly, they may have adverse effects before we get beneficial effects,” Dr. Fine said.

“There's absolutely no substitute for developing a sound, trusted relationship with the patient that allows you to go very, very slowly,” he added.

After all, there's good reason to take your time today treating elderly patients' pain. “Tomorrow, it's going to be us,” said Dr. Kaye.