Success in ACOs depends on collaboration

Physicians should consider culture, autonomy and resources before jumping in.

Although still in their infancy and without a firm definition, accountable care organizations (ACOs) have increased more than 40-fold, from 10 in early 2010 to 469 in January of this year, according to David Muhlestein, senior analyst at Leavitt Partners in Salt Lake City, Utah.

One reason might be that ACOs, loosely categorized as groups of clinicians who assume responsibility for managing and coordinating care for a defined group of patients with an eye toward improving quality and cost-effectiveness, offer physicians a chance to take the reins in guiding health care and health care economics going forward, said Thomas Denberg, MD, PhD, FACP, executive vice president and chief strategy officer at Carilion Clinic in Roanoke, Va.

“For physicians who recognize that the health system is broken, ACOs are an opportunity to be part of something big and have influence over where health care is going, especially in primary care,” he said.

But before jumping into such an arrangement, experts agreed, physicians should examine three key areas of the relationship: the ACO's culture and priorities, the level of autonomy they can retain and what resources and technology the ACO will offer.

ACOs 101

Accountable care organizations fall into two basic camps, Medicare and private sector. But both are alike in several key ways. Neil Kirschner, PhD, ACP's senior associate for health policy and regulatory affairs, summed up their commonalities at ACP's annual scientific meeting, Internal Medicine 2013, in San Francisco in April. Both can contract with payers, they're governed by participating clinicians, they are able to measure the quality and efficiency of health care delivery effectively, and their payment is aligned with the quality and efficiency of the care they deliver.

There are three categories of Medicare ACOs: Shared Savings, Advance Payment and Pioneer. Shared Savings ACOs share in savings from a fee-for-service benchmark, with the amount based on quality of care. Advance Payment ACOs are mostly start-ups receiving yearly and monthly payments that are advances from anticipated savings. Pioneer ACOs are more established programs with experience in care integration and value-based models of payment. They are generally expected to transition from fee-for-service payments to population-based payment, where they are paid per beneficiary each month.

Advance Payment and Pioneer programs are part of an initiative of the CMS Innovation Center. “They are exploratory models, basically tests, and if they are viewed as successful, the secretary of [the Department of] Health and Human Services has the right to make them part of Medicare without going back to Congress,” said Dr. Kirschner.

He added that Pioneer programs typically are large systems that may have had experience with data reporting and information management that allows them to do a good job of collecting patient data. These programs are willing to ramp up quickly and take more risk; they also expect to receive a larger part of shared savings. On the other hand, Advance Payment programs lend themselves better to smaller practices or rural practices, where Medicare gives them money up front to help them develop the infrastructure they need to succeed, Dr. Kirschner said.

Private-sector ACOs, he said, may have both Medicare and non-Medicare contracts and a broader range of financial arrangements, including but not limited to shared savings, capitation, bundled payments, and pay-for-performance incentives.

Finally, public and private-sector ACOs may be physician-led or hospital-led.

What's available depends in part on geography, and it's not a level field, said Robert Berenson, MD, FACP, institute fellow and expert in health care policy at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. “In some areas there is little ACO activity, and physicians may be facing diminishing reimbursements from Medicare and private insurers alike. But in other areas, there are numerous ACOs. In Boston, ACOs care for more than 60% of patients.”

Dr. Denberg agrees. “Don't assume that ACOs will be the same everywhere. The pace and culture may be different. In urban environments there is more competition and pressure to create ACOs than in rural environments.”

Although ACOs are rapidly expanding, there is still time for physicians to take leadership positions in creating new ACOs, said Gregory Pawlson, MD, MPH, FACP, who is on the board of directors at SE Healthcare Quality Consulting.

“The real choice is whether you do this yourself and align with other physicians or sign on to an existing, often hospital-led, ACO. In some parts of the country, you might be better off doing it yourself, pulling together primary care practices with subspecialties like cardiology, gastroenterology or other specialists that manage and co-manage chronically ill patients, knitting together systems and services like care coordination, and deciding together on structure and governance,” he said.

In some cases, Dr. Pawlson added, both Medicare, through the advanced payment model, and private insurers may be able to provide practices with some resources to help with the transition.

The process of forming and ramping up a physician-led ACO takes anywhere from two to five years, so it is important that physicians decide if they can wait that long or if there is an integrated system already in place that meets their needs, Dr. Pawlson added.

Hospital-led ACOs offer a few advantages, but physicians who are considering one would be wise to get a feel for its culture, said Dr. Berenson.

“They can raise the capital and tend to have sophisticated data systems in place, but managing the ACO may be their primary act, rather than a secondary act as it would be in a busy practice where patient care is the first priority,” Dr. Berenson said. He stressed that there should be a focus on the physician-patient relationship and physicians' ability to act in the best interest of their patients.

Dr. Denberg cautioned physicians to find out what the hospital leadership's priorities are.

“For some, ACOs are all about consolidation and a way of ensuring that they'll have a referral base,” he said. “Assess just how serious the hospital is about reconfiguring the way health care is delivered, and ask senior leadership to provide examples or data to support the happy-speak they will give you about reducing readmissions. They should be willing and able to explain their approach to care management.”

Collaboration in care

A key aspect of accountable care is collaboration among primary care physicians, between primary care physicians and specialists, and between physicians and other health professionals, the experts said.

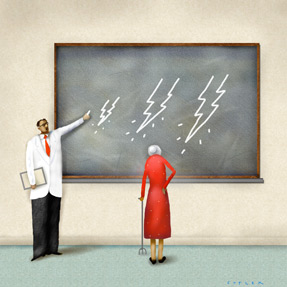

“It's completely different than the way physicians who have been in practice for 20 or 30 years are used to operating,” said Mark A. Levine, MD, FACP, chief medical officer of the CMS Denver office in Colorado. “Suddenly you have responsibility not just for patients when they're in your office, but for a whole population of patients over time, and you can't manage that alone.”

To that end, he said, patient-centered medical homes can be an ideal practice model for ACOs, as they allow clinicians to practice at the top of their licenses and improve patient outcomes even as they work together to streamline care.

“If I were being recruited to lead or join an ACO, I would want to know whether the organization has the commitment and resources to hire nurses, pharmacists, and care managers, as well as data analysts who will build the kind of infrastructure required for providers to perform and succeed,” said Dr. Levine. “I would want to know if there is a hospital involved, or if there will be partnerships with other entities like long-term care facilities, nursing homes, and home health organizations, and I would want to understand each participants' motivations.”

Yet collaboration is not without its challenges. On the surface, it may seem like physicians who participate in ACOs give up a certain amount of autonomy. They will have to take a step back and let other clinicians contribute their expertise (i.e., pharmacists coordinating medication therapy management or diabetes nurse educators counseling patients on lifestyle interventions). Physicians will also have to work within the ACO's guidelines to meet goals for patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

But how much autonomy physicians will sacrifice depends on how they define the term, said Dr. Pawlson. “If you consider autonomy to be doing what you want, when you want to, just because you want to, and everyone else doing as you say because you say so, then yes, you'll lose some autonomy.”

However, if physicians would like to reduce their own administrative burden, and their focus on keeping their professional autonomy within the physician-patient relationship, they might feel differently. “I think what most physicians want more than anything is to retain autonomy over the physician-patient relationship. They don't want someone dictating how they interact with patients,” said Dr. Pawlson.

Role of technology

There's no question that success in an ACO depends on data, or, more precisely, access to it. Physicians need to know how their patients and care populations are doing in terms of meeting outcome goals so they can adjust and improve care accordingly. Physicians also must be aware of events like emergency department visits, hospitalizations and follow-up care to keep track of costs.

Although electronic health records (EHRs) can provide a snapshot of patient care, that is just one part of a much larger data management effort, said Peter S. Basch, MD, FACP, medical director at MedStar Health in Maryland, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington, D.C., and chair of ACP's Medical Informatics Committee.

“It would be unusual to find an EHR system that could provide useful information about the relative cost of individuals one refers to, facilities one uses, or tests one orders,” Dr. Basch said. “There's still a role for multiple information systems.”

Dr. Basch emphasized that physicians should look for data management systems that provide information that is both useful and usable. “Useful is what you need to know; usable means it's presented in such a way that you can act on it. Otherwise, you can end up with a broad brush of information. You might be told that your patients with X illness are in the fourth quintile, but what does that mean and what do you do with it?”

He used cancer screening as an example. “A negative report can come from something as simple as how often a patient is screened. If the patient has been screened more often than guidelines suggest, you and your colleagues can change practice to fall within the guidelines.”

Reports and information should be provided to physicians in a timely manner, said Dr. Basch. “It's like using a GPS. You don't want one that tells you that you should have turned left an hour ago. The value of reports is that they prevent you from going in the wrong direction in the first place.”

Physicians in leadership roles within an ACO should see for themselves what the systems can do before signing any agreements, said Dr. Basch. “Never ask the question, ‘Can your system do this?’” he said. “You're likely to hear that of course it can, and the vendor wouldn't be lying. But what they usually mean is that given enough money and time to develop features and enhancements, they could make a system do anything. Instead, a better question is, ‘Is your system already doing this now, and if so, may I see how?’”

When shopping around for systems and vendors, physicians may encounter the term “ACO-ready” and wonder what that entails.

“Usually it means that it's ready for some kind of action to be taken that will enable it to serve the ACO's purposes. For example, someone has to connect interfaces or tweak reports and data visibility in an EHR so the information can be used in a relevant way,” said Dr. Basch. “It's like having a satellite-ready radio in your car, but not knowing if there are any satellites in your geographic area, or more importantly, that are broadcasting something worth listening to.”

Dr. Pawlson said that physicians should be able to tap into aggregated data, track their patients' progress through the health care continuum and provide other clinicians with pertinent information. “Can you press a button and see all the patients with A1cs over 10? Or people who haven't had a mammogram, or haven't filled a prescription you gave them? Can you transmit clinical information to a specialist you just sent a patient to see because the patient has an unusual form of hypertension?”

ACO, not MCO

Critics of accountable care express concerns that ACOs sound too much like managed care organizations (MCOs). But there are several key differences between ACOs and MCOs with respect to payment, information gathering, and patient involvement, said Dr. Kirschner.

“Payments to ACOs are risk-adjusted and reflect the severity of illness in the population being covered. In the 1990s we weren't as skilled as we are now in doing that type of risk assessment. Physicians would be given a set of payment for a population, and if treating that population required more money than was provided, they were stuck,” he said.

He added that quality is a driving force. “In the old days, physicians would get money even if they didn't provide services, but in an ACO, that's not possible. They must meet the quality benchmarks.”

Beyond that, patients are more empowered in ACOs because they are not restricted to a network of clinicians the way they were in MCOs, and there is nothing stopping them from seeing the clinicians they want, particularly with Medicare ACOs.

But perhaps most important, an ACO's success lies partly in patient satisfaction. “Patients get to decide whether you meet some of your quality measurements,” said Dr. Kirschner. “If there are long waits for getting appointments or in the waiting room, that will affect patient satisfaction and they will have input on that. Winning in an ACO environment means meeting patient expectations.”

“When you are out there looking at different organizations, consider whose interest they feel is paramount. It shouldn't be the hospital's, the administrators', the physicians' or that of any other professional,” said Dr. Levine. “The priority should be the patients. They have to be the bottom-line criteria ethically and practically, or how effective will the ACO really be?”