Doctors don't have to dread discussing dieting

Many internists are not discussing obesity and weight loss with their patients, even though they have the best opportunity to offer counseling about diet and new drugs that are now available to help.

Obesity researcher Sara Bleich, PhD, knows firsthand the frustration of counseling someone about weight loss. Her best friend has struggled with her weight for a long time.

“She would always ask me, ‘What are some tricks for losing weight?’ I would always say some version of ‘Eat less, exercise more,’” said Dr. Bleich. “Ten years later, she said to me, ‘I think I know why I'm not losing weight.’ I lean in; what's she going to say? She said, ‘I think I'm eating too much and not exercising enough.’”

The prescription for weight loss may be simple, but as anyone who has ever tried it knows, the execution is not. And the prescription options are also about to get a little more complicated, with the recent FDA approval of two new drugs for weight loss.

Whether these new options will significantly affect Americans' ability to execute their weight loss plans is a matter of debate among experts. They agree, however, that general internists hold much of the responsibility for determining the use of these drugs and generally facilitating their overweight and obese patients' weight loss.

“Many internists are not discussing obesity and weight loss with their obese patients,” said Kimberly Gudzune, MD, assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and an internist at the Johns Hopkins Digestive Weight Loss Center in Maryland. “Or if they are, patients are not remembering the message.”

She estimated that 20% to 40% of obese patients report receiving any weight loss counseling from their primary care physician.

Physicians' reluctance is understandable for several reasons.

“It's hard for physicians to actually tell a patient that they're obese or overweight, because the reaction from the patient can be hard for them to deal with,” said Dr. Bleich, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore.

And, although obesity is one of the most common health risks facing Americans, weight loss is not a topic physicians are taught a lot about.

“Only something like a quarter of medical schools even have a course in nutrition. The average physician knows less about nutrition than a slightly overweight housewife who reads up on it,” said Richard Atkinson, MD, emeritus professor of medicine and nutritional sciences at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Finally, weight loss care is hindered by the usual bugaboo of primary care practice—time. “Teaching someone how to not eat when they're hungry, how to exercise when it's not comfortable, is going to be a lot bigger task than can be done in eight minutes,” Dr. Atkinson said.

The good news is that there are things a physician can do with those eight minutes that appear to make a difference in their patients' weight. “Patients who are told they need to lose weight report more confidence, report more actively trying to do so,” said Dr. Bleich.

Some additional actions can increase the impact of that advice, although each expert had a slightly different perspective on the best course of action. “The challenge about weight loss and weight management is that there really isn't a good gold standard,” Dr. Bleich acknowledged.

She favors giving patients a few quick tips: Avoid sugary beverages, moderate portion size and drink water (“People's cues are really messed up and they think they're hungry when they're actually thirsty,” she said). Then, patients who are interested should be referred to a nutritionist for additional counseling.

It would be ideal if every overweight patient could see a nutritionist, but insurance coverage and clinician shortages make that unrealistic, according to Dr. Atkinson.

“If you took all the primary care physicians in the country, and all their nurse practitioners and all the dieticians, there simply aren't enough to treat two-thirds of the American population,” he said.

That's why he recommends sending patients to an evidence-based commercial weight loss program.

“[Physicians] need to become comfortable with a high-quality commercial weight loss program in their area, one that is doing reliable work and has reliable programs,” Dr. Atkinson said, citing Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig as two examples.

Dr. Gudzune added, “A non-profit weight loss program such as Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS) may be a lower-cost option for patients.”

Cost is an important consideration in weight loss treatment, agreed Dr. Bleich.

“If you are a low-income patient, living in a food ‘desert’ area with little access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and your physician says to you, ‘You need to start cooking fruits and vegetables,’ that's in one ear and out the other,” she said.

One physician-led program recently found an innovative solution to that specific problem (see sidebar on this page). But cost is only going to become a bigger issue if pharmaceuticals become a more prominent part of the weight loss treatment picture.

“We're going to need obesity drugs. Obesity is a chronic, lifelong, incurable disease,” said Dr. Atkinson. “We're in the position with obesity now that we were in with hypertension when I was in medical school all the years ago. We had lousy drugs that didn't work very well and had side effects.”

Yes, even though he sees pharmaceutical treatment as the most likely solution to obesity, he views the current options as lousy. “Relatively lousy, but they are a start,” he qualified.

A start is about what patients will get from lorcaserin hydrochloride (Belviq). It was approved earlier this year for adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater or those with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater who have at least one weight-related condition such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes or dyslipidemia.

In clinical trials, the drug, a serotonin 2C receptor agonist, helped patients lose 3% of their body weight after adjustment for placebo. “That is not meaningful and additionally the drug is not completely safe,” said David Gortler, PharmD, a former medical officer on the FDA's lipids and obesity team and current associate professor of pharmacology at The Georgetown School of Medicine in Washington, D.C.

“That drug approval was kind of a shocker to me,” added Dr. Gortler. “It didn't even meet the FDA's own white paper requirements for efficacy.”

“I think lorcaserin by itself is doomed,” said Dr. Atkinson. “It's not going to sell huge amounts of product, because unless it's used with another drug, it doesn't cause a big enough weight loss.”

He did see some promise if the FDA were to allow the combination of lorcaserin with other drugs, such as phentermine.

“It's almost impossible to name a chronic disease, if you've got a bad case, that is not treated with more than one drug. Yet the medical establishment thinks we need to have a single magic bullet [for obesity],” Dr. Atkinson said.

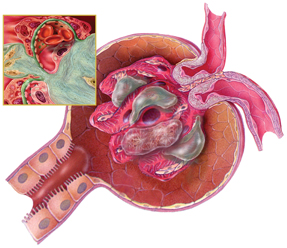

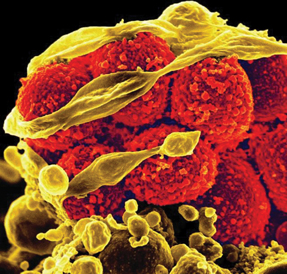

Dr. Gortler agreed about the necessity of combining therapies in order to achieve significant weight loss using pharmaceuticals. “When you're dealing with satiety, you're dealing with hundreds and perhaps thousands of different neuroendocrine markers. As soon as you inhibit one, you've got many more taking over,” he said.

The other new drug recently approved by the FDA does combine medications. Qsymia is made up of topiramate and phentermine. It helped patients achieve significant weight loss in trials. “Weight loss after one year was between 14% and 15% at the highest dosing regimen. This is quite remarkable,” said Dr. Gortler.

There's a catch, though. “Efficacy is not the issue; safety is the issue,” he said, noting that patients taking topiramate have reported problems with global confusion. “In some cases, there were people who complained they were driving home and suddenly couldn't remember where they lived,” Dr. Gortler said.

However, Dr. Atkinson predicted that may be less of an issue with the new drug. “The combination will probably cause somewhat fewer side effects than topiramate alone,” he said.

It won't remove the risk of birth defects, however. Women of reproductive age, who would likely be major consumers of the medication, should be tested for pregnancy monthly, according to the Qsymia drug labeling. Patients should also receive ongoing monitoring for metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia and increased creatinine.

Qsymia became available for sale in September. Belviq is expected to become available sometime next year. Both drugs come with recommendations to monitor for changes in mood and symptoms of congestive heart failure, and the Belviq label additionally suggests complete blood counts, because leukopenia and anemia have been reported.

All of these issues should be discussed with patients considering a weight loss drug.

“Patients need to understand how these medications work, the amount of weight loss that they can reasonably expect, as well as the side effects and risks of each medication,” said Dr. Gudzune. “I typically spend at least 10 minutes discussing this information with patients to determine how a weight loss medication might fit into their weight loss plan.”

The medications might be most useful for patients who have already begun to execute a plan, with less than complete success. “It's so hard in the beginning. You're going to the gym five days a week, you're modifying your diet, and you're not seeing any movement on the scale,” said Dr. Bleich.

“If you combine that with a weight loss drug which shows relatively quicker weight loss, psychologically that can really help a person stay on the right track, because they're actually seeing that they're making a difference,” she added.

David Katz, MD, FACP, founder of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center in Derby, Conn., summed up many of the experts' perspective. “Mostly [the drugs] may be an alternative to surgery for those who need a ‘jump start’ and are then willing to transition to a lifestyle-based approach,” he said. “They are both rather poor drugs.”

How soon we'll have better drugs is uncertain. “This is not going to be something we are going to be able to easily cure with pharmacology. In our lifetime, there's not going to be a single pill that's going to cure obesity on a long-term basis,” said Dr. Gortler.

Dr. Atkinson offered a little more hope. “There are a number of different companies trying to work on the gut hormones. The problem is ... they have to be injected. People like to inject themselves like they like a hole in the head,” he said. But, he added, “I'm hoping that at some point we're going to figure out a way to get cocktails of these gut hormones.”

In the meantime, internists can help their overweight and obese patients by raising the issue and offering them all the currently available resources. “The primary care physician is going to have to marshal his or her resources to help the obese patient,” Dr. Atkinson said.