‘Goldilocks' goal for diabetes and CKD

Managing kidney disease in diabetes requires meeting individualized parameters and balancing risks in nephrology and cardiology. Learn whether more aggressive treatment is warranted in this population.

To prevent or manage kidney disease in type 2 diabetes, aggressive treatment might not always be best. Several prospective studies published this year suggest that treatments should be more individualized and that ambitious targets for glucose and blood pressure control may boost rather than benefit other health risks, according to experts.

“It really comes down to the Goldilocks theory of everything. It's got to be done just right,” said Steven Coca, DO, an assistant professor in the nephrology section of the department of internal medicine at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “Too much of anything is not necessarily the right way to go.”

Part of the challenge is that two of the major risk categories, potential cardiovascular effects and further kidney damage, are intertwined, said Kwame Osei, MD, FACP.

While preventing kidney disease progression remains important, the cardiovascular risks in diabetic patients are frequently more worrisome, he said: “A lot of them will die from cardiovascular disease before they reach end-stage kidney disease.”

Reconsidering aggressive control

Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), published in 2011 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, indicate that doctors have been treating diabetic patients more aggressively. The percentage of patients taking glucose-lowering drugs increased from 56.2% to 74.2% from 1988 to 2008, and the use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (11.2% to 40.6%) and lipid-lowering drugs (8.9% to 50.2%) was also up.

Yet the proportion of diabetics with diagnosed kidney disease remained essentially unchanged over the same 20-year span, hovering between 34.5% and 36.4%. Without better prescribing, those rates likely would have been higher, said Ian de Boer, MD, a JAMA study author and an associate professor of medicine and adjunct associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

But the findings do raise several related questions, including whether new drugs are needed to target other markers besides albumin, the current medication focus, he said.

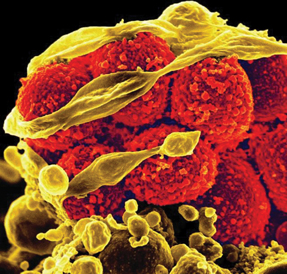

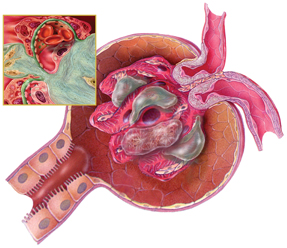

“By focusing on albuminuria as the most important marker of diabetic kidney disease,” he said, “we have been ignoring low GFR [glomerular filtration rate] as a related but separate manifestation of kidney disease and have not been sufficiently targeting that [with medications].” More medications should be developed, he said, to combat GFR loss.

Dr. Coca reached a similar conclusion regarding the clinical benefits of targeting albumin levels with intensive glucose lowering after authoring a meta-analysis of seven studies. The meta-analysis, published May 28 in Archives of Internal Medicine, involved 28,065 adults with type 2 diabetes and scrutinized the relative benefits of intensive glucose control.

Researchers found that aggressive glucose control with a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) goal of 7.1% or lower, depending on the study, significantly reduced the development of microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria. But the evidence was inconclusive that kidney effects were prevented, including worsening disease or kidney failure, Dr. Coca said.

Given the relatively low rate of poor clinical outcomes in the patients studied, one possible explanation is that there weren't sufficient patients to capture any meaningful clinical benefits, he said. “We couldn't prove [that there was] no [clinical] effect,” he said. “We just said that we're lacking positive data.”

One of the seven studies included in the meta-analysis, the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial, has been particularly influential in calling into question whether aggressive glucose control provides any benefits, including to the heart, experts said.

ACCORD researchers found that intensive therapy, with HbA1c targets of less than 6.0%, failed to reduce cardiovascular events in 10,251 type 2 diabetes patients with cardiac risk factors. (Patients were either randomized to the intensive therapy group or the standard group, with an HbA1c goal of 7.0% to 7.9%.) In fact, patient deaths overall increased by 22% compared with standard therapy.

“The problem is we don't have the data to show exactly why they died,” said Dr. Osei, one of the ACCORD investigators, who directs the Diabetes Research Center at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. It could be related to hypoglycemia, which did increase in the intensive therapy group, or other health effects, he said.

Tailoring treatment

These uncertainties have led to a more personalized approach, as exemplified in new guidelines on hyperglycemia from the American Diabetes Association, published in Diabetes Care in June, Dr. Osei said.

“It's a different guideline than we are used to; we are used to numbers,” he said. The new guidelines recommend less uniform goals, stating that an HbA1c of 7.5% to 8.0% or even higher might be appropriate for certain patients, such as those with limited lifespan remaining or a history of severe hypoglycemia.

An HbA1c target of 7.5%, for example, might be sufficient in an 80-year-old woman newly diagnosed with diabetes who might not progress to kidney failure for decades, Dr. Osei said.

On the other end of the spectrum, type 1 diabetics are particularly likely to reap the benefits of an aggressive approach starting at diagnosis, ideally at an HbA1c below 7%, because those patients haven't yet developed complications and have decades of life ahead, Dr. de Boer said.

“That's where the evidence is strongest for tight glucose control,” he said.

Optimal targets also are being reassessed regarding blood pressure control, said George Bakris, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director of the Comprehensive Hypertension Center at the University of Chicago.

Traditionally, striving for blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg has been recommended for adult diabetics with kidney disease, including in the National Kidney Foundation's 2007 guidelines, which a spokesperson said are due to be updated this November. But that approach has been based primarily on retrospective analyses, Dr. Bakris said.

In recent years, though, three randomized studies involving adults with chronic kidney disease have compared targets below 140/90 mm Hg with targets less than 130/80 mm Hg. The findings of those studies, which included the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) and the Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy 2 (REIN-2) Trial, were summarized in a 2011 review article in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“None of them showed a benefit in the lower blood pressure group in further slowing kidney disease,” Dr. Bakris said.

The three studies didn't include any patients with diabetes. But there is no reason to believe the findings would be different in that population, Dr. Bakris said. At this point, the evidence indicates that a blood pressure target of less than 130/80 mm Hg is not necessary for all patients and less than 140/90 mm Hg is likely sufficient, he said.

And research has yet to back up another practice, prescribing RAAS inhibitors in patients newly diagnosed with diabetes even if they don't have hypertension or microalbuminuria, Dr. Bakris said. That approach was debunked in a pivotal biopsy study published in 2009 in the New England Journal of Medicine, he said.

The study compared two RAAS inhibitors (enalapril and losartan) and a placebo drug in 285 patients with type 1 diabetes who had normal blood pressure and albumin levels. The findings, based on kidney biopsies at the study's start and after five years, showed that the drugs didn't slow kidney disease progression.

If a diabetic patient's blood pressure is elevated, it must be treated, Dr. Bakris said, “but it doesn't really matter what [drug] you are using.” However, he stressed, if the patient also specifically has measurable albumin, and definitely if they have macroalbuminuria, they should be prescribed an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker.

Weighing these various patient risks is not easy, and in some areas physician approaches can differ, Dr. Osei said.

Take statin prescribing. Studies have shown that a diabetes diagnosis, in and of itself, elevates a patient's cardiovascular risk equivalent to that of someone who already has suffered a heart attack. For that reason, some doctors believe all diabetics should be taking a statin, even if they don't have kidney disease or elevated cholesterol, he said.

But, Dr. Osei added, “These drugs are not benign. The question is: How do you know which patient will get into trouble with a statin?”

Dr. Osei prefers a more individualized approach. He doesn't typically prescribe a statin in diabetic patients without kidney disease or other cardiac risk factors unless their low-density lipoprotein cholesterol approaches 100 mg/dL.

Emerging guidance

Should albumin continue to be monitored? Yes, because studies have shown that increasing albumin levels are associated with greater cardiovascular risk, said Dr. Bakris. “However, that does not mean that you have kidney disease,” he said.

Dr. Coca agreed. “Even though it [albumin] falls short in predicting clinically meaningful endpoints, it's the best thing we currently have,” he said.

Albuminuria stages, along with GFR stages, are expected to be incorporated into a new prognostic map, dubbed a “heat map” by clinicians, to provide a color-coded risk profile for kidney disease patients. A preliminary version of the new staging and prognostic assessment, anticipated to be published in final form soon, appeared in Kidney International in 2010. It's being developed by an international clinical group, dubbed KDIGO, for Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, which is finalizing guidelines for the classification and management of all kidney disease patients.

The goal is to provide a better prognostic road map for doctors, said Michael Shlipak, MD, FACP, chief of general internal medicine at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and a member of the KDIGO working group. Based on where the patient falls along the heat-map style grid, he said, “You'll be able to define prognostically if they will have kidney failure down the line. You'll be able to define the risks and benefits of treatment.”

Patients who have more advanced disease, or whose doctors are having difficulty treating them, should be referred to a nephrologist, according to the American Diabetes Association's 2012 guidelines. Still, given the relative scarcity of nephrologists, primary care doctors likely will care for the bulk of these diabetic nephropathy patients in the years ahead, Dr. Bakris said.

The good news is that primary care physicians can apply some of the recent findings as they strive to protect both the heart and the kidneys, Dr. Bakris said. Studies published in the last five to six years have sharpened the clinical picture considerably, he said.

“Now we have at a minimum one prospective trial, and in some cases three or four prospective randomized trials, addressing specific questions that were assumed before,” Dr. Bakris said. “Now we have answers, and the answers are consistent.”