Know the patient to achieve statin benefits

That statins work is without question. And with costs falling due to many drugs in the class going generic, physicians are now refining when to prescribe the ubiquitous drug class based on the degree of risk.

The patient is in his mid-30s and, though healthy, has a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of 170 mg/dL due to genetics and lifestyle. Although this patient's risk of coronary disease is low—for now—Mark J. Pletcher, MD, MPH, would take the opportunity to point to evidence that it's bad for coronary vessels to have high cholesterol for a long time, and to bring up the possibility of treatment with statins.

“Having high cholesterol levels during young adulthood is associated with higher levels of atherosclerotic heart disease later in life,” he said. When Dr. Pletcher talks to patients like this in his internal medicine practice, he emphasizes the importance of having a healthy lifestyle during young adulthood, and not deferring lifestyle improvements until middle age. “What is not yet clear, however, is whether young adult patients with high cholesterol and high lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease should take statins.”

Statins are one of the most heavily studied classes of compounds. The evidence of their benefit is “unparalleled and incredible for its consistency … to the point of being boring. This is not an issue of efficacy,” said Thomas A. Pearson, FACP, PhD, MPH, author of ACP's PIER chapter on lipid disorders.

In fact, he noted that since 2000, there has been a 22% reduction in heart-disease related deaths among men and a 23% reduction among women due in part to increased use of statins, beta-blockers and aspirin, according to a June 10, 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine. This decrease occurred despite the increase of certain cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and diabetes.

However, experts' thinking about when and how to use statins appears to be changing. Although no one knows for sure what the long-awaited ATP4 guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), due out for review and public comment next spring, will recommend, they will probably reflect the spate of recent research on statins. That research has ranged from investigations into the connection between bad cholesterol in young adulthood and risk for atherosclerosis later in life to explorations of how or whether to treat older patients. There are also new data on tailoring treatments based on a patient's overall risk-benefit profile.

What may most affect physician behavior now is cost. As statins continue to come off patent—atorvastatin (Lipitor) will be available as a generic in November 2011—treatment will cost 25 to 50 cents rather than three to five dollars a day, said Dr. Pearson, a professor in the University of Rochester's department of community and preventive medicine in Rochester, N.Y.

“Cost is now history. It's irrelevant,” he said. When cost is off the table, what's left is increased pressure, especially given the focus on prevention in health care reform, for physicians to weigh the risks and benefits to determine if and how their low- and high-risk patients should take statins.

“We need to get down to the basics of knowing our patients, knowing their risks, and lowering risks with the wonderful tools we have,” Dr. Pearson said. “That's the statin story … and that should be the renaissance of general internal medicine.”

New perspectives

Even before the arrival of the ATP4, physicians' approach to statin use has changed from ATP3's original guidance, released in 2002 and updated in 2004, which added a focus on primary prevention in persons with multiple risk factors, said Benjamin J. Ansell, FACP< professor in the divisions of general internal medicine and cardiology at UCLA School of Medicine and co-director of the school's Cholesterol, Hypertension, and Atherosclerosis Management Program.

In the 1980s, the public health message was to “know your cholesterol.” In the 1990s, it was to “know your cholesterol and treat to lower the level of LDL.” Now, Dr. Ansell said, physicians are advised to apply a more global definition of risk. “Increasingly, candidates for aggressive lipid lowering do not have elevated LDLs. In patients with diabetes, hypertension, and/or low HDL [high-density lipoprotein], LDLs are often not elevated,” he said.

According to Rodney Hayward, ACP Member, it's more important to talk to patients about overall cardiovascular risk than cholesterol levels. “Our work suggests compelling evidence that a treat-to-target approach is inefficient and does much less good in absolute terms than our [tailored] approach,” said Dr. Hayward, co-director of the Ann Arbor VA Health Services Research Center of Excellence, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Michigan, and co-author of a Jan. 19, 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine article on optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease.

He suggests calculating the benefit of starting a statin, usually a lot at the beginning of treatment, he said, as well as of increasing the dose, which he said gives less benefit to those with a five-year risk of 10% to 15% and increases the likelihood of side effects. However, he said a statin is always a good idea if a patient is at moderate to moderate-high risk.

“If the five-year risk is more than 12% to 15%, getting on a high-potency statin at a high dose is really important. It might be worth the higher pill pay and greater risk,” he said. Higher doses of Crestor can cost as much as $162 per month, for example, according to a June 2010 Consumer's Report Best Buy Drugs report on statins. Higher doses are also linked to more side effects such muscle aches, soreness, tenderness, and weakness in particular, as well as rhabdomyolysis.

While higher statin doses yield bigger reductions in coronary events and LDL, it's unclear whether it's the dose or the LDL level that really matters. “It's difficult because the studies generally compare statin to placebo, or fixed dosages of statins, neither of which could be conclusive in answering this question,” Dr. Ansell noted.

Although he urges physicians to follow current NCEP guidance, he said newer research on statins is moving the drugs into more widespread use, despite some controversy. He pointed to the results from the 2008 JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Primary Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) study, which he said show that in patients with relatively normal or low cholesterol levels and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, statins further reduce LDL cholesterol and the risk of coronary events and strokes.

But while statins reduce LDL levels, they don't raise HDL levels much. For patients who need that kind of treatment, Dr. Ansell said niacin appears to complement statins by increasing HDL cholesterol. However, he noted that studies of combination lipid-lowering approaches are less numerous and less conclusive than those assessing statin monotherapy. “The real issue with applying the results of the niacin clinical trials, though, is that doctors are reluctant to use the drug because of its perceived intolerance,” with such effects as flushing or pruritus, he said.

There's also controversy about statins' effect on all-cause mortality. An Aug. 17, 2010 article in Archives of Internal Medicine found little evidence for statins' benefit on all-cause mortality for high-risk primary prevention. Author Kausik K. Ray, MD, said that both pro- and anti-statin factions have tried to use his results to make their points.

However, he cautioned that the results should not be used as a reason to stop using statins. Instead, he suggested that internists use the results to tell patients that statins can reduce the risk of heart attacks but not other causes of deaths. “Will they prolong life in the short term? Very minimally,” said Dr. Ray, professor of cardiovascular disease prevention at St. George's University of London.

The age factor

The key to treatment decisions may be lifetime risk estimates, said Mark J. Pletcher, associate professor in the departments of epidemiology and biostatics and medicine at UCSF and lead author of an article in the Aug. 2, 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine on the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development In young Adults) study.

The study found that nonoptimal levels of LDL and HDL during young adulthood, even in low to moderate ranges, were associated with coronary atherosclerosis in middle age and that maintaining optimal lipid levels, especially for LDL, throughout young adulthood could help prevent coronary heart disease.

“It really looks like past exposure is a strong predictor of atherosclerosis,” he said.

The results argue for knowing what patients' cholesterol levels are in young adulthood, he said. However, they don't address what to do once those numbers are known. “It begs the question of whether to use statins in young adults. The study can't answer that,” he said. Other trial results don't help much because they have focused on subjects who are middle-aged or older—the mean is typically around 60 years—and the results are difficult to extrapolate to patients in their 30s, Dr. Ansell said.

Dr. Ansell's own conclusion is not a strong recommendation for statins in younger patients at this point. He has opted to focus on diet and exercise for most, and acknowledged that physicians won't be treating the majority of at-risk young adults with statins on a broad basis any time soon.

According to Dr. Ray's study data, using statins over the short term, for example four years, likely would have a very modest benefit in a 35-year-old. Age is the biggest driving factor behind risk, he said. A 65-year-old is more likely to gain from statins' effect in preventing heart attacks and stroke because his absolute risk is higher. Because most people stay on statins for life, their use in younger people should be based on lifetime risk. However, if a patient has a previous history of cardiac disease, there's no debate about age, Dr. Ray said.

But what about very elderly patients over age 75? “If your patient is 85 or 90 years old with no heart attack [history], would you initiate a statin? Theoretically they are at very high risk, but something else has probably helped you prevent heart disease. We don't really have the answer to what to do here,” Dr. Ray said. In patients with end-stage heart failure or with end-stage renal disease on dialysis, statins offer little benefit, he noted, so they would probably be discontinued given the associated risk of diabetes with increasing age.

Physicians should consider patients on a case-by-case basis, especially the growing 80-year-old and above population. “[Viewing] them as one homogeneous group is not the right approach,” cautioned Pamela Ouyang, ACP Member, professor of medicine and deputy director of the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

She noted that the Framingham Heart Study based its scores on people age 75 or younger, so scores are not well-established for those who are older and who do not have known cardiovascular disease. “We know much less as to how much [these patients] benefit from starting statins,” she said.

While taking a statin might stabilize plaque buildup—Dr. Ouyang said most patients in their high 80s have advanced cardiovascular disease—the question is whether there's enough benefit to justify starting to take a statin throughout the final years of life if they do not have clinically evident cardiovascular disease. The priorities should be identifying which patients are truly at high risk and getting other risk factors, especially blood pressure, under control, she said.

The ‘land of choices'

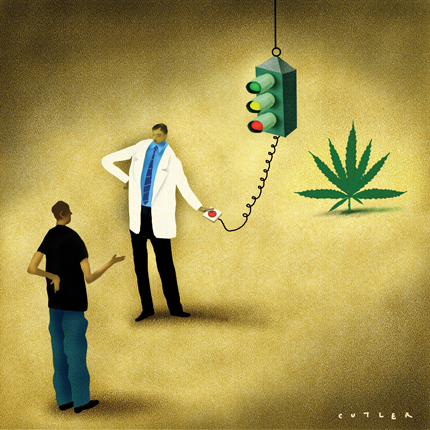

It's always important to engage the patient in decision-making, but it's particularly important when it comes to statins, what Dr. Pearson calls “the land of choices.” Dr. Ansell agreed. “Patients need to understand that their cholesterol level may not be the trigger for the statin. We need to consider everything, including age, blood pressure, blood sugar, family history, and the patient's ability and willingness to change.”

According to Dr. Hayward, patients who fall into the gray zone below thresholds must make a decision that's right for them. “Whatever the patient decides is fine because of the small amount of potential benefit,” he said.

Still, physicians often have an uphill battle to get patients, many of whom look for a quick fix, on board with lifestyle changes (see sidebar). “It would be foolish to assume that benefits of statins or any medicine to improve cardiovascular risk would allow one to have license to eat whatever they want or not exercise, even though many patients do just that,” Dr. Ansell said.

This conversation is also the time to talk about statins' side effects, particularly muscle aches. Although the side effects have gotten significant coverage in the consumer press, the reputation may stem from the drug's early days when the first versions tested in dogs caused cataracts and liver function abnormalities, Dr. Pearson said. Those problems were due to the toxic effects of early compounds and animal tests, he noted.

In fact, the FDA didn't make statins over-the-counter a few years ago because of the potential effect of such a decision on the doctor-patient relationship, not because of the drugs' side effects, noted Dr. Pearson, who was involved with that process. “The FDA concluded that safety of statins was not at issue,” he said.

Of course, there are unknowns about the effects of long-term statin use. “We really don't know what the effects of 50 years of statin treatment starting in young adulthood will be,” Dr. Pletcher said. “But if early treatment could lower heart disease rates by 70% to 80%, as some claim it might, that would counterbalance almost any plausible side effect we might dream up,” he said.

Other benefits?

Rather than unexpected side effects, statins may have unexpected benefits. According to Dr. Pearson, statins reduced heart transplant rejections by 50% in early studies, and there's evidence to suggest that those who got H1N1 pneumonia got milder cases if they were on a statin.

For now, he said, internists will become more important than ever in this debate. And there's much to debate, given the success of statins, new thinking about how they might be used, their increasing cost-effectiveness, and the advent of health care reform. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's focus on risk assessment and personalized prevention is yet more reason for internists to talk to patients about their cardiovascular risk.

“I think internists are going to have to play the key role because they're oftentimes going to be referred patients with moderate to high cholesterol levels,” Dr. Pearson said. “It's a wonderful opportunity for internists to make an enormous impact.”