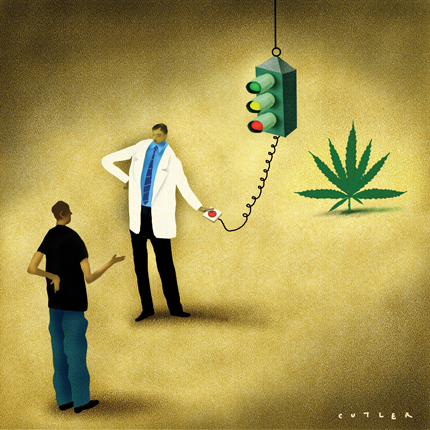

Marijuana requests: Relief or ‘permission’?

Fourteen states have legalized medical marijuana. Internists who have issued the controversial prescriptions describe how they sort out legitimate uses from trivial requests.

Internists are facing increasing requests from patients for medical marijuana “permission.” Fourteen states now allow physicians to authorize marijuana use, and the federal government has said it will not interfere.

Patients have a variety of reasons for asking their doctor about marijuana use, ranging from the more legitimate (terminally ill patients desperate for pain relief) to the trivial (people who want to get legal protection for an activity they engage in anyway).

Yul Ejnes, FACP, an internist in Cranston, R.I., recently declined to sign a marijuana form for a young man who presented with chronic back pain.

“He had a friend with cancer who suggested marijuana to him,” said Dr. Ejnes. “In fact, patients often tell me they recently used some marijuana with a friend and it made them feel better. Of course, a pint of Jack Daniels could have had the same effect on them, and we aren't advocating that.”

However, internist Molly Cooke, FACP, has a large number of HIV patients in her San Francisco practice and has authorized marijuana for about 20. Doing so can be challenging, she said. Marijuana usage is not easily studied in a blinded trial, and it can be difficult to tell what's behind a patient's request. Dr. Cooke often finds that people who ask her for medical permission are polysubstance abusers looking for “cover” in case police catch them with marijuana.

“If I really think those patients have a condition that merits a trial of it, I will do it, but I tell them their relationship with drugs is an issue I don't want to complicate,” she explained.

For patients in whom she sees legitimate uses, she believes a small amount of marijuana is harmless, and in fact helpful.

“The evidence we do have is excellent that inhaled THC [tetrahydrocannabinol] is effective in easing symptoms of severe nausea, such as experienced by chemotherapy patients. It also helps stimulate the appetite in anorectic patients, such as in HIV, which is where I probably use it most,” she said.

Before California changed its laws, Dr. Cooke would occasionally advise chronic patients that a small amount of marijuana could ease their particular symptoms and that they should “ask around” to obtain some.

“With chemotherapy patients, the nausea and vomiting can be so miserable that their body comes to dread getting it and just the thought of going for their next treatment can make them sick,” she said. “They can really benefit from the relaxing effects of marijuana. It really is the best choice for some of them.”

Learning the ropes

The mechanics of authorizing medical marijuana for a patient are similar in most states that allow the practice. Physicians sign a form stating that they believe marijuana could help relieve a person's medical issues; the form is not a prescription. The patient gives the form to a marijuana store or other source that he or she has chosen, and that entity keeps it on file for one year.

The patient can ask the physician to renew the form annually. Dr. Cooke said that most often, these requests are granted. She does not consider the possibility of addiction to be an issue when making these decisions.

“A patient could become dependent—for example, an anxious patient might use marijuana to excess as a way to manage anxiety. However, there is no physical dependence or addiction,” she said. “Heavy users of smoked marijuana can develop lung disease, like cigarette smokers, and of course it is reasonable to discuss patterns of use to try to determine if the patient is doing nothing but sitting around smoking, but there is no real monitoring regimen otherwise.”

For internists in states that have newly approved medical marijuana usage, Dr. Cooke advises proceeding slowly before signing any forms. She does not know of any formal training in this area, but recommended reading all the available literature, particularly as it pertains to any subspecialty in a practice, and talking to physicians who have related experience.

“Explore your collegial networks and consultants just like you would with anything else that is unfamiliar to you,” Dr. Cooke advised.

How to decide

When faced with a medical marijuana request, Providence, R.I., internist John S. Straus, ACP Member, asks himself if using marijuana will make the patient's life better.

“That is the litmus test that we should use when recommending any powerful medication—it should help patients lead a more functional or productive life, if it's not purely for symptom control for a terminal disease,” he said. “I do not want to just legitimize the use of marijuana.”

He has signed medical marijuana forms for about 30 patients and stressed that he follows state guidelines, using it only in patients with conditions that cause severe pain, nausea or vomiting. Relieving anxiety related to these conditions is not an official use, but he thinks it has merit for some patients.

Dr. Cooke agreed. “Chronic pain is complicated and anxiety just makes it worse, so any anxiety reliever helps with that pain,” she said.

To detect any addictions that may need to be addressed, Dr. Straus performs drug tests on all new patients asking for marijuana. He finds many patients who request medical marijuana approval from him are already using it and want some legal protection.

“I think the best thing about the legalization of marijuana is that it allows us to have an honest discussion with our patients about their lives. We don't have to ‘play cop’ with them anymore,” he said.

Saying no

Like many physicians, Dr. Cooke declines medical marijuana requests far more often than she approves them. She will never approve marijuana for short-term nausea or for new patients.

“Patients often ask us for things that we do not believe are right for them, such as Vicodin, and we tell them no,” she said.

Dr. Ejnes believes the law that allows medical marijuana in his state is meant to provide compassionate care for those few patients with extreme pain or severe wasting.

“It is not meant to be just another option for the management of routine pain,” he said. “Sometimes the public sees it as having a broader use than that.”

Some physicians, Dr. Ejnes said, may sign marijuana forms because it is easier than taking 10 minutes to discuss more appropriate ways to manage a patient's condition. And Dr. Straus said he knows of some physicians who sign marijuana forms for anyone on buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) to help them avoid legal hassles. In Rhode Island, the majority of forms have been signed by a relatively small number of doctors.

“Some of that is legitimate, as some are practices that see a lot of HIV or cancer patients, but others are questionable,” Dr. Ejnes said.

Herbert D. Kleber, MD, a professor of psychiatry and director of the Division of Substance Abuse at Columbia University, cited a New York Times article about a doctor in Boulder, Colo., who does three- to five-minute marijuana assessment exams for $150.

“He only asks two questions: ‘Do you have any conditions that could be helped by marijuana? And do you have any conditions in which marijuana use is contraindicated?’ He's making millions of dollars off this farce,” he said.

Insufficient evidence

Dr. Kleber believes there is not enough evidence for any physician to recommend marijuana to patients. The marijuana plant has 400 constituent elements, he noted, and the lack of any uniform guidelines for making cigarettes from it means potency levels can vary greatly.

“We have systems in this country to make sure that medications are safe and effective, and marijuana has not gone through these proper channels,” he said. “It has been approved by referendum.”

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine recommended that local medical boards set up a system to allow patients who are truly suffering to access cannabis derivatives such as Marinol in a controlled setting. Dr. Kleber agrees with that course of action. ACP also supported use of nonsmoked forms of THC in its recent position paper on the therapeutic role of marijuana (see sidebar).

“People complain that Marinol takes longer to take effect, but if they start taking it and continue taking it, it will prevent new pain. Chemotherapy patients know when their next appointment is and they can take the Marinol in plenty of time for it to be working,” Dr. Kleber said.

For some physicians, marijuana is more than a medical issue. If they have moral objections to medical marijuana or see it primarily as a stepping-stone drug, they should not feel compelled to authorize its use, said J. Fred Ralston Jr., FACP, president of the American College of Physicians.

“ACP in general does not advocate physicians providing care that they are opposed to, but they should recognize the right of the patient to get that care elsewhere,” he said.

Dr. Kleber, for one, thinks that laws allowing marijuana usage did not outline the appropriate indications clearly enough. The “poster child” for passage, he said, was a grandmother suffering from intractable cancer pain, but he believes the drug is being used today mostly for more minor problems such as trouble sleeping and vague pain symptoms.

“All of these conditions have better treatment options available,” Dr. Kleber said. “Marijuana is not a benign substance. When someone becomes addicted, you have in fact hurt their lives.”

Dr. Ejnes agrees that the data in marijuana's favor are not yet definitive. While he doesn't categorically oppose all marijuana use, he has yet to sign a patient's form.

“We do not have enough good evidence comparing its efficacy with other treatments. It obviously can provide some symptomatic relief, but not as a first- or second-line approach,” he said. “It should be reserved for patients with terminal diagnoses and few options.”