Start at the top to get to the bottom of a diagnosis

ACP Member C. Christopher Smith reconsiders a patient's self-reported diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome to uncover the true cause of his symptoms.

ACP Member C. Christopher Smith, MD, an internist at the hospital where we work, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, submitted the case of a 32-year-old man whom he saw as a new patient for primary care. The man complained of urgency and frequency of urination.

In relating his medical history, the man told Dr. Smith that he had been diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). His bowel problems began in college and were precipitated by the death of his mother. He associated recurrent episodes of cramp-like pain and diarrhea with stress and anxiety. A barium enema had been performed at the onset of his symptoms and was reported normal. Although IBS was not his current complaint, the patient told Dr. Smith that his symptoms were ongoing, although intermittent.

It is reasonable for a physician to accept a diagnosis of IBS when it is provided directly by the patient as part of a medical history and appears to be typical, in this case related to the extreme trauma of losing a parent and then flaring with periods of anxiety. The patient had accepted the diagnosis and did not request additional evaluation. But Dr. Smith, like most clinicians, keeps in mind a short list of related diagnoses that are easy to miss.

Certain complex conditions can be difficult to diagnose because they often have overlapping symptoms and findings with more common disorders, such as IBS. Celiac disease is one of the easy-to-miss diagnoses that Dr. Smith keeps at the forefront of his thinking. Other clinicians have told us that Cushing's syndrome is a rare but easy-to-miss diagnosis in the setting of diabetes mellitus and hypertension; inferior myocardial ischemia often masquerades as indigestion; and aortic aneurysm may be overlooked as a possible cause of back pain.

Drawing from a knowledge base to generate a hypothesis has been termed a “top down” or “working forward” approach to clinical diagnosis. (Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002 Vol. 9.) Using this strategy, the physician begins with a potential diagnosis drawn from his knowledge and experience then obtains additional history, physical examination and laboratory data to confirm or refute the hypothesis.

Dr. Smith does not work up every patient with a diagnosis of IBS for celiac disease, but rather looks for specific clinical and laboratory clues that justify further investigation. In this case, he noted that the patient was quite thin, weighing 149 pounds at a height of 5 feet 9 inches, and wondered if this might be a symptom of malabsorption.

Dr. Smith ordered screening laboratory tests including a complete blood count. The patient had a hematocrit of 37% with a mean corpuscular volume of 73, consistent with iron deficiency anemia. Both findings of low body weight and anemia were taken by Dr. Smith as sufficient evidence to more deeply pursue the possibility of celiac disease.

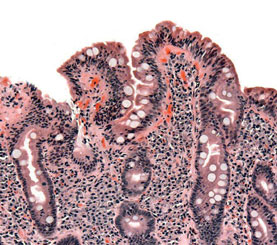

Indeed, endomysial antibodies were positive in this patient and an endoscopic biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of celiac disease. A gluten-free diet resulted in a remarkable change in clinical status. “He was thrilled with how he felt so much better,” Dr. Smith told us. He was able to gain weight for the first time since college. “In fact, he gained more than he needed,” Dr. Smith added. The patient's anemia completely resolved. No cause was found for his urinary symptoms; they resolved spontaneously and did not recur.

Start at the bottom

In contrast to the top-down approach described above, a bottom-up approach is data driven. The doctor works from specific physical and laboratory findings to generate a hypothesis that explains the findings. In this case, the finding of iron deficiency anemia in a young man might have led to consideration of celiac disease.

We were reminded of another case of undiagnosed celiac disease where a doctor used top-down thinking described in “How Doctors Think.” This case was ultimately unmasked by Myron Falchuk, MD, a gastroenterologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. In this instance, a woman in her early 30s had seen more than 30 physicians since the onset of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea in her late teens. She was diagnosed with bulimia and anorexia nervosa and had suffered numerous complications of apparent starvation, including iron deficiency anemia and osteoporosis with bone fractures.

She had been hospitalized in a psychiatric facility several times for treatment of her condition and only seemed to worsen with increased feedings. Indeed, Dr. Falchuk's patient did have an eating disorder, but also had celiac disease. He made the correct diagnosis by listening to her claim that she had tried to eat and still was unable to gain weight.

Back to the top

Generally, early in a case when there are little data, top-down thinking predominates. As laboratory data accumulate, the bottom-up process becomes more important. In the case diagnosed by Dr. Falchuk, the patient had seen numerous physicians, generating an enormous amount of clinical data. Yet data-driven thinking had failed to yield the correct diagnosis. Similarly, Dr. Smith's patient had a prior evaluation that had not yielded the correct diagnosis.

Most of us have seen patients who have been extensively evaluated for an unresolved problem and present with reams of records, lab results and imaging. In this setting, we generally begin with a bottom-up approach, focusing on the findings from prior testing. However, sometimes, as in both cases above, it is necessary to put aside preexisting data and begin again from the top to arrive at the correct diagnosis.