The best self-management is ‘specific, do-able and realistic’

Second in a three-part series: Simple ways to engage patients in their own health care.

Patients with chronic conditions generally know that poor lifestyle choices set them up for serious health problems down the road unless they're willing to make some significant improvements. Yet getting patients on that path is no small feat.

Lectures overlaid with fear-fueling warnings about what might happen may have some effect. But this approach is unpalatable to some doctors and off-putting to many patients. Engaging the patient in self-management through goal setting, education and support could be far more effective, say internists who have tried and succeeded with this technique.

At Mayo's Franciscan Skemp Healthcare, in LaCrosse, Wis., internists are making headway by using a scorecard during visits. The card—a graphic form that shows A1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, weight change and follow-through on recommended tests—is provided to the patient and placed in the chart. The report compares patients' actual results to where they should be if they're “at goal” in order to delay disease progression.

“We print out the patient's own scorecard, which is essentially our scorecard, too, to see and show them how they're doing,” said Michael J. O’Brien, ACP Member, who chairs the health system's internal medicine department. “You're never going to be successful if you just focus efforts on your side, without getting the patients buying in to it.

“Part of that education is for motivation. If a patient doesn't understand why he should do something, it probably isn't going to happen,” Dr. O’Brien explained. He added that if patients gain some sense of the long-term benefits and see progress, they start looking for and even reporting short-term benefits of better disease control.

“Giving patients something tangible to look at,” Dr. O’Brien said, “resonates more than simply saying, ‘You're doing better.’”

When his group started the scorecard project in 2006, which has a dual aim of encouraging physicians to improve management of diabetes patients, only about 5% of patients met their goals in control and recommended screenings. Now the figure for some is closer to 30%. “That means that even the best physicians have 70% of their patients who could improve. But it's at least a start,” he said.

Simple motivators

Engaging the patient positively in his or her own management can ultimately reduce the internist's burden and may confer a host of health-improving benefits. Right now, Dr. O’Brien said, although his group is focusing on diabetes control, “You tend to hit a couple of others, like cholesterol and blood pressure, in the process.”

As such, the potential implications for addressing obesity and pre-diabetes are apparent, he suggested, provided that “larger societal issues and insurance coverage” for nutritional counseling don't confound practices' efforts.

John Guzek, FACP, and colleagues at Physicians Health Alliance (PHA) in Scranton, Pa., also have discovered the value of using profiles to increase patient engagement and propel proactive provider management of chronic illness. The 55-physician multispecialty practice has implemented Your Diabetic Profile, a report that lists individual patients' measures compared to target goals, and also provides guidance on how the patient can close the gap through his or her own actions.

“The introduction makes the point that diabetes complications are easier to prevent than to treat,” said Dr. Guzek, PHA's chair of quality improvement. But it's having the actual profile in hand, he added, that makes the difference to patients in their self-management.

“The patients love it, because they take it home and compare it to their previous one, and can see if they're doing better,” Dr. Guzek said. The staff affixes stars beside improvement areas on the profile, which goes over well with patients.

“Simple things, like a star, can be very motivating for the patient, we've found—and also for the staff members involved,” he said. On the provider side, the profile generates pop-ups in advance of the visit to flag needed tests or exams, or dangerously high blood pressure, for example.

‘Specific, do-able and realistic’

Both PHA's and Franciscan Skemp's initiatives illustrate that the gains patients make are going to occur primarily outside the confines and reach of the internist's practice.

“We have to remember that self-management not only can be done outside the clinical setting, it usually is,” said Chicago internist Doriane Miller, MD, section head for general internal medicine at Stroger Hospital of Cook County. “Our patients self-manage every day, deciding what to eat, and whether or not to run in the morning instead of sleeping in.”

The support comes in, she added, when providers and “micro-systems” of nurses, health educators and nutritionists collaborate. Whether that's loosely or in a structured manner, the support can boost the patient who has set health-improvement goals.

If patients enlist providers' help in setting the goals, it's vitally important that the goals be “specific, do-able and realistic—and have a time frame or limit,” said Dr. Miller, who also is director of the national New Health Partnerships initiative, created to foster best practices in engaging patients in self-management. That helps keep patients from becoming discouraged or giving up, especially those with chronic illness or those who are developing them because of serious health risks.

“Patients may have a goal in mind, but the question is: how do you eat an elephant one bite at a time?” she said. Internists and their practice staff, she added, can and should play a key role in helping patients figure out how confident they are that they can achieve the goal.

“Research has shown that if we're able to do that and patients feel confident about that [their ability to achieve the goal], it strongly correlates with patients' ability to execute that change,” she said.

Resources can help

The challenges to such supported self-management, Dr. Miller acknowledged, are that some physicians haven't developed the skills to work in a collaborative fashion, or don't have time to engage in an exchange that could add several minutes to the encounter.

The former may be addressed by using tools and resources offered through New Health Partnerships, the national initiative aimed at fostering best practices in self-management support. The time factor, after the initial conversation at least, might be alleviated by having staff step in to monitor and support patients' progress.

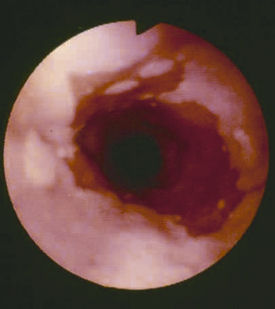

Also available is the ACP's Diabetes Portal. The portal offers a wide range of resources, from patient education materials and health-improvement guidance to detailed information on lab tests, medications and diabetes complications.

“I can't be all things to all people—none of us can. But incorporating other members of the practice team improves my ability to provide the kind of care that patients need, and engages patients in that process,” Dr. Miller said.

It's critical to reconfigure the practice's care processes so that it isn't just the doctor doing this work, she advised, noting that many practices have found a workable balance in having nurses or medical assistants do much of the goal-setting work. “It's a question of right-sizing the job to ensure that the team is involved,” she said.

Internist Bob Mead, MD, president of Bellin Medical Group in Green Bay, Wis., uses that team approach to start the process. When a newly diagnosed diabetic patient's blood is drawn for lab work, the phlebotomist gives the patient a pamphlet on health goals and a “Patient-Generated Goal” form, which helps focus the conversation once the patient is in the exam room. The nurse meets with the patient after the exam to go over the action plan, and follows up by phone two weeks after the visit to see how the patient is progressing. The call is repeated two weeks later if the initial patient report wasn't positive.

“This is the key part. If you just do the goal setting and send them on their way, you're not holding patients accountable and you're not giving them feedback,” Dr. Mead said, noting that the latter two increase the likelihood that patients will make needed health improvements.

The initial goal-setting session may take an extra five minutes but once the team is engaged in supporting the patient, the internist's time expenditure in supporting self-management typically goes down. By way of caution, he advised internists to avoid scheduling, back to back or in a single day, a slew of appointments involving initial goal-setting.

Other important objectives are to ensure that the practice has the latest lab results ahead of the visit, Dr. Mead said, and to let the patient drive the discussion about goals.

“Many patients have been in that didactic mode for so long that they don't know what they want from the visit, and simply say things like, ‘I know I should exercise 30 minutes a day,’” he said. “You have to switch from that didactic mode to finding out what patients really want.”