Human, animal experts offer advice on H5N1

ACP and Annals of Internal Medicine gathered experts for a case-based discussion on H5N1 avian influenza.

ACP and Annals of Internal Medicine first began organizing virtual forums in 2020 to discuss a novel virus that exploded into a pandemic and has since become endemic. The most recent forum, held on Sept. 6, discussed a virus that everyone very much hopes does not become endemic: H5N1 avian influenza.

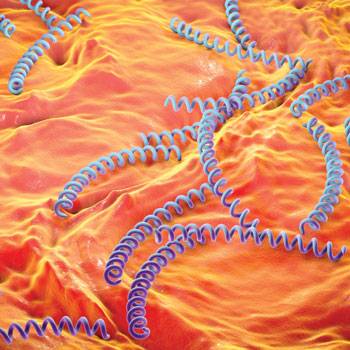

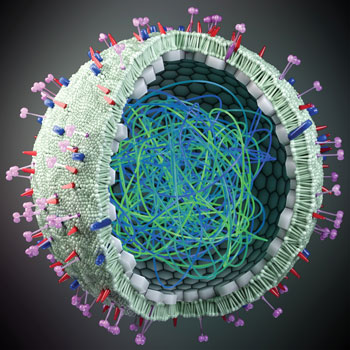

“Avian flu is a viral disease that spreads in wild birds, with outbreaks in domestic poultry and other animals,” explained Christine Laine, MD, MPH, FACP, Editor-in-Chief of Annals and a Senior Vice President at ACP.

The H5N1 strain has also been found sporadically over the years in humans who have had contact with animals, with some devastating consequences. “While the severity of infection varies, the cumulative case-fatality rate exceeds 50%,” said Dr. Laine.

At the time of the forum, the CDC had reported avian flu in U.S. dairy cows, unpasteurized milk, and at least 13 people this year. (A 14th case, the first without a known occupational exposure to any infected animals, was announced by the CDC on Sept. 6.) “Thankfully, none of the infections were severe. However, these events have heightened concerns about the potential for avian flu to result in another pandemic,” Dr. Laine said.

To help avert and/or prepare for that possibility, the forum gathered moderator Deborah Cotton, MD, MPH, FACP, Deputy Editor of Annals, and three other expert panelists for a case-based discussion. A summary and video recording of the forum were published by Annals on Sept. 9.

The first case featured a hypothetical patient who works in the office on a dairy farm in rural Michigan and presents with bilateral conjunctivitis and general malaise. “We know that Michigan is one of the states that has H5N1 among dairy cows,” said Demetre Daskalakis, MD, MPH, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases in Atlanta.

The patient's reported symptoms also cause concern. “Presenting with bilateral conjunctivitis and general malaise actually tracks pretty closely to what we have seen so far in the 13 cases reported in 2024 and also the one case in 2022,” he said. “Beyond just conjunctivitis, people have presented with classic respiratory or influenza-like illness. That can include fever. It can include coughs. It can include sneezing. It can include other symptoms that maybe we sometimes associate with flu, gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, but very prominent is conjunctivitis.”

The fact that the patient reports no direct contact with cows is slightly, but not entirely, reassuring, as H5N1 has been proven to transfer by fomites, Dr. Daskalakis noted. To clarify this risk factor, he recommended asking the patient whether he has worn eye or respiratory protection when in the barn where the cattle are kept.

Forum attendees were asked to decide on the proper testing for the patient. Many chose a throat or conjunctival swab, but the correct answer is both, Dr. Daskalakis said.

“Some of the individuals who had H5N1 detected have had positive throat swabs, but sometimes they don't, so conjunctival swabs are really important to send,” he said. “That is something that you would send to the public health laboratory because they actually have the test that needs to be run on conjunctival specimens looking for flu, specifically H5N1.”

While those swabs are out for testing, the patient should be advised to isolate. “As we learn more about whether or not this is an H5N1 infection, trying to limit the potential for exposure of other people to this individual [is necessary], though it's important to say we have not seen person-to-person transmission in the United States,” Dr. Daskalakis said.

“I completely agree,” said panelist Shira Doron, MD, MS, professor of the clinical and translational science program at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. “I would just add one detail … You've got this throat swab, or more likely, nasopharyngeal swab, cooking in a local lab that's going to come back long before the eye swab that went to the public health lab. A negative throat or nasal swab does not reassure you that this person doesn't have H5N1 and is not really a license to get out of isolation, unfortunately.”

The third panelist also agreed, noting that his medical expertise was not with human patients. “Certainly your suspicion would go way up if this was actually one of the farms that had been diagnosed as positive for presence of H5N1 in the cows themselves,” said Jonathan Runstadler, PhD, DVM, MS, professor and chair of the department of infectious disease and global health at Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine in North Grafton, Mass.

He tackled the next case, about the risk of exposure to H5N1 from eating eggs from a neighbor's chickens. “Influenza viruses grow very well in eggs … and this is a virus that has caused outbreaks in poultry populations across the country … so there's some basis for concern that the virus is in our environment and it is circulating,” said Dr. Runstadler.

However, this concern is likely outweighed by the reasons not to worry about H5N1 in eggs, he added. One is that chickens would typically manifest symptoms if they had the virus, so as long as the chickens are healthy, the eggs are OK. The other reassurance is that cooking and pasteurization have been proven to kill the virus.

“As long as the person wasn't planning to down raw eggs from the neighbor in this case, there should not be a lot of concern in terms of consumption,” Dr. Runstadler said.

There are other foods that potentially carry H5N1 risk, though, Dr. Doron noted. “Some of the things I would be more worried about are unpasteurized milk. It can take a while for cows to manifest symptoms of disease, and they could be affected, and we know that the virus concentrates in the milk, so I would not advise anyone to drink unpasteurized milk ever,” she said.

Less is known about whether unpasteurized aged cheese and hamburger should be a concern. “I found out this week that, at least in California, hamburger is made from dairy cows, whereas a steak is made from beef stock. It's not worrying me enough to stop eating hamburgers, but it's worrying me enough to want to see more studies on that,” said Dr. Doron.

She took on the third and final case of the forum, about vaccination. “At this moment in time, there's no recommendation to vaccinate any humans in the U.S. or animals for H5N1, though there are vaccine candidates in the Strategic National Stockpile that seem like they would work against it,” Dr. Doron said.

She noted that the U.S. stockpile's supply of vaccines against H5N1 is currently being enlarged, in case it's needed. “But with relatively few identified cases, … with no known cases of severe disease, with no genetic evidence that the virus is mutated to be more virulent or more transmissible human-to-human, now is probably not the time for a mass vaccination campaign or even a targeted vaccination campaign.”

Public health authorities want to avoid the situation that occurred in 1976, when a new vaccine was widely distributed in response to swine flu and turned out to cause many cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, while the flu outbreak itself was actually relatively mild, Dr. Doron explained.

Dr. Cotton wondered whether similar lessons have been taken from the COVID-19 response. “Are we in a better position now?” she asked. “How much of the controversy that we still haven't really sorted out, in terms of mask-wearing, in terms of school closures, in terms of all kinds of restrictions, is going to make our response even more complicated?”

The answers are “a little bit of a mixed bag,” said Dr. Daskalakis, before offering reassurance by listing some of the ways the U.S. is better prepared for a flu outbreak than it was for SARS-CoV-2.

“We have a really good ability to see what's happening with flu in the country, as well as to develop vaccines preemptively,” he said. “The national surveillance system for influenza, since February 2024 … has tested about 46,000 people for influenza down to type and subtype, so technically have been testing for H5N1.”

The government has also been testing wastewater for the virus, Dr. Daskalakis reported. “When we see an H5N1 detection, we are finding an animal or animal product explain the situation, so we're not actually seeing human disease,” he said.

The state of vaccine development is another advantage, while public attitude might be a bit of a loss from the pandemic, Dr. Daskalakis continued. “We have some work to do to recover from some of the things that have happened to confidence around vaccines as well as public health voices that people trust,” he said.

Finally, greater awareness of the relationship between human and animal health is another positive takeaway of COVID-19, added Dr. Runstadler.

“The whole concept of one health and interactions that are important between humans, animals, and environments that we share … is emphasized by some of the things that are happening,” he said. “Events, including the current concerns around avian flu, have helped, or at least provided a venue, for bringing some of the parties involved in human medicine and veterinary medicine closer together.”