Intimate partner violence: An epidemic hiding in plain sight

Despite a recommendation to screen for intimate partner violence and the many tools available to physicians, barriers to implementation remain.

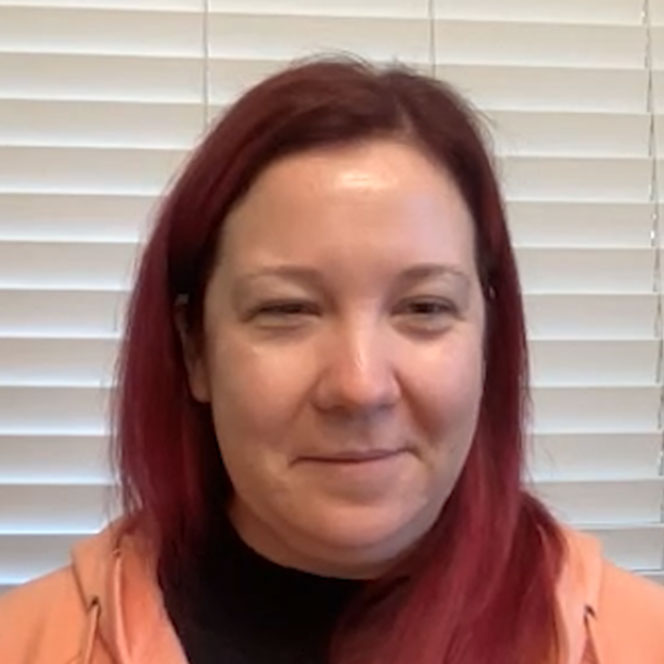

Emergency medicine physician Tamara O’Neal was shot and killed by her ex-fiancé while working at Mercy Medical Center in Chicago on Nov. 19, 2018. The shootout also claimed the lives of a police officer, a pharmacy resident, and the killer. Her killer had a prior restraining order against him for threatening his former wife.

Dr. O’Neal was the first physician in her family. As a medical student, she made it her mission to connect with other Black medical students so they could support each other through the rigorous medical school journey. She chose emergency medicine as a specialty because she felt it was where she had the most to offer underserved communities.

When we picture a physician, we rarely picture someone who has experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), yet physicians are not immune to violence by their partners/spouses. Women and men who are younger, have lower income, are members of racial and ethnic minorities, identify as LGBTQ, and/or live with disabilities are at disproportionately high risk of IPV. Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to IPV, as are women with substance use disorders. Women serving in the military are also at increased risk for intimate partner violence.

Intimate partner violence is defined as sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking. Over one-third of Americans have experienced IPV. Most women affected by IPV first experience it before age 25. Multiracial and Black women report the highest lifetime and 12-month prevalence of IPV. About one in four women and one in 10 men have experienced IPV in their lifetimes, according to an issue brief published in December 2019 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The BulletPoints Project, a resource for clinicians and medical educators on firearm injury prevention, reports that approximately 50% of reported IPV homicides are by firearms. Guns are also used to coerce, threaten, and terrorize victims. It's estimated that 1 million American women alive today have been shot or shot at by an intimate partner.

Women who have experienced physical or sexual abuse are significantly more likely than others to report overall poor health, chronic pain, depression, and memory loss. Additionally, women with a history of abuse are more likely to experience headaches, chronic pelvic pain, abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, and other gastrointestinal disorders. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use are also sequelae of IPV. Pregnant women who experience IPV are more likely to experience peripartum depression, obstetric complications, preterm birth, and perinatal death.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns exacerbated pre-existing risk factors for IPV. Financial stressors, school closures, and loss of personal space contributed to an estimated 8% increase in domestic violence in the U.S. during the pandemic, as reported in a June 29 article in the Harvard Gazette.

How can we help our patients who are at risk for or have experienced intimate partner violence? The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended routine screening for intimate partner violence in women of childbearing age (Grade B evidence) since 2013. These screening instruments accurately predict IPV in the past year among adult women: HARK (Humiliate, Afraid, Rape, Kick); HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream); E-HITS (Extended-Hurts, Insults, Threatens, Screams); PVS (Partner Violence Screen); and WAST (Woman Abuse Screening Tool). However, screening rates remain suboptimal. The 2017 Kaiser Women's Health Survey found that only 27% of women reported having discussed IPV with their clinician.

Barriers to screening from the clinician perspective include lack of time, personal discomfort with the topic, lack of education and training, and concern about legal issues and mandatory reporting. Implementing a universal workflow, training, and screening protocols in an existing program may alleviate some of these barriers.

Concerns over stigmatization by health care professionals is a significant barrier to disclosure for patients. Additional barriers include fear that children might be taken away and fear of being judged negatively by the health care professional or their own families and friends. Fear of their partner also often prevents patients from disclosing. Other reported barriers are the perception that the clinician is unsympathetic, disinterested, not maintaining eye contact, or not actively listening. Feelings of shame, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and guilt can also prevent disclosure. Of note, women physicians who have experienced IPV are less likely than women in other professions to report their abuse.

Creating a safe environment with adequate privacy is critical to increasing the comfort level of women who are at risk for or have experienced IPV. It can also be helpful to have posters, pamphlets, and palm cards addressing IPV in the office to signal that the practice is committed to the safety and well-being of its patients. The Veterans Health Administration and others have proposed moving toward the use of more person-centered language and referring to someone who commits IPV as a “person who uses IPV” instead of a “batterer, abuser, or perpetrator” and to a “person who experiences IPV” rather than a “victim or survivor.” Shifting the language used to refer to IPV can help decrease stigma and barriers to care.

When a woman screens positive for IPV, she should either be provided or referred to ongoing support services. Interventions include referral to mental health, social services, and local and national IPV advocacy organizations. These organizations can provide safety planning, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other supports. The Affordable Care Act requires private plans and Medicaid expansion programs to reimburse clinicians when they provide IPV screening and brief intervention services to women at no additional cost to the women. There's increasing evidence that IPV counseling and interventions can significantly benefit health and safety and that those receiving an intervention are much more likely to end a relationship because it feels unhealthy or unsafe.

ACP has advocated for the increased availability of training to help our patients achieve safety and security and improve their health status. To that end, the College recently released two comprehensive online training modules on intimate partner violence.

As internal medicine physicians and trusted professionals, we can play a critical role by educating ourselves to recognize intimate partner violence in our patients and by identifying local and national organizations that can provide a wide variety of services to those who need them. These steps can improve outcomes and reduce the burden of violence experienced by millions of women in the U.S.