Pinpointing primary hyperparathyroidism

With targeted testing, especially in those who present with kidney stones and bone density issues, internists can help patients with this disorder get appropriate care.

Primary hyperparathyroidism affects at least one in 1,000 of the general population, yet studies have estimated that it is often missed in U.S. patients. With targeted testing, especially in those who present with kidney stones and bone density issues, internists can help patients get appropriate care.

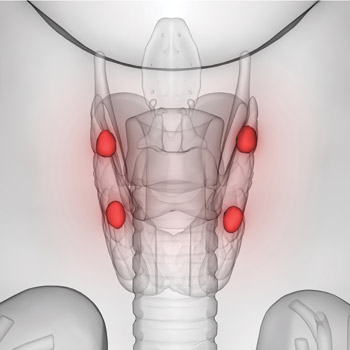

In primary hyperparathyroidism, one or more of the four parathyroid glands makes too much parathyroid hormone, which causes excess levels of calcium in the blood and can predispose patients to loss of bone calcium and production of kidney stones. Other associated symptoms can include fatigue, memory issues, frequent urination, and psychologic symptoms. In severe cases, the condition, left untreated, can lead to heart attack, stroke, demineralizing bone disease, and renal failure. The condition is its own systemic disease with no known genetic cause in most cases, and while it does not discriminate among specific populations, it most commonly presents in postmenopausal women.

A 2019 study in JAMA Internal Medicine showed that only 23% of patients with chronic hypercalcemia receive further testing of parathyroid hormone (PTH) level and only 13% of those who meet diagnostic criteria undergo curative parathyroidectomy. Another study, published in JAMA Surgery in 2020, showed that about one in 20 patients with kidney stones present with hypercalcemia, yet only 25% of them were screened for primary hyperparathyroidism.

This is where internists can help fill the gaps, experts said.

“Internists actually have the most important role in that they often see these patients way before us specialists get our hands on them,” said Calyani Ganesan, MD, MS, lead author of the JAMA Surgery study and instructor of nephrology at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics in Palo Alto, Calif. “The first step when someone presents with a stone is to ask if they have any calcium derangements. Is their serum calcium high? And that should automatically get someone to check a PTH level.”

Brendan C. Stack Jr., MD, chairman of the Endocrine Surgical Section of the American Head and Neck Society and recently professor of and chairman of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Springfield, Ill., stressed that hypercalcemia shouldn't be ignored. “I can tell you all sorts of stories over my career of patients coming in and saying, ‘Yeah, my doctor's known about this [elevated calcium] for a couple of years, but we never really did anything about it initially until I had a kidney stone, or until I broke a bone, or because I've been feeling really crappy … and that resulted in the referral to see you.’”

Because calcium levels can vary for many metabolic reasons, a random high level can often be dismissed as erroneous, according to Sophie Y. Dream, MD, assistant professor of endocrine surgery at Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “And then from there, the workup for primary hyperparathyroidism just stops. Where if you have a high serum calcium, the next step should really be to investigate why that happened, and part of that is to look at the parathyroid hormone level and the serum calcium at the same time to see if those two numbers are indicating that there might be something else going on.”

Ordering the right labs

Jesse D. Pasternak, MD, MPH, section head of endocrine surgery at Sprott Department of Surgery at the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada, served as senior author on a study published in JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery in January, which aimed to improve care for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism by proposing 18 quality indicators for workup, diagnosis, and management. It outlined the top five most important quality indicators for primary care specifically, which involve diagnosis based on calcium measurement as well as parathyroid hormone, creatinine, and 25-hydroxy-vitamin D levels.

One big hurdle standing in the way of diagnosing primary hyperparathyroidism is which tests are ordered as routine bloodwork at each institution. While calcium is sometimes included, PTH is not. In her work with veterans, Dr. Ganesan said the calcium level is embedded in the basic metabolic panel, but this is not the case at Stanford. “There isn't an automatic check for calcium like for cholesterol annually or your kidney function,” she said. “But a stone I think would be a good reason to check the calcium, and if you have a calcium and it's high, you should definitely check a PTH.”

Other reasons for high calcium levels include “some cancers, some granulomatis diseases, but if you have that high calcium and a stone—a clinical manifestation of primary hyperparathyroidism—you should get a PTH,” Dr. Ganesan added.

Time to refer

Surgery is the usual treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism, and at this point, the internist should refer the patient on for specialty care. However, to whom exactly can depend on the practice setting.

After ordering and reviewing bloodwork, Dr. Stack said, internists have “done really all they can for the patient, and to try to do any more would I think delay the patient's timely treatment.” He recommends referral to an endocrinologist who is knowledgeable about hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism. “In theory, all endocrinologists should be well acquainted with this, but I will tell you in actual practice there are a lot of endocrinologists that focus on diabetes and obesity and they really don't emphasize this disease in their practice,” he said.

It's likely that the patient will end up seeing an endocrine surgeon, but Dr. Stack said he wouldn't encourage direct surgical referrals at this point unless internists know their health system has a high-volume parathyroid surgeon who is familiar with the disease.

Dr. Pasternak, however, warned against including too many practitioners with one patient's care. “Because it's a surgical disease, when there's too many people involved, there's more likelihood for the patient to not get to the surgeon,” he said.

Dr. Dream attributes underdiagnosis to how overwhelmed primary care doctors can be in the U.S. health care system, especially since primary hyperparathyroidism isn't as common as hypertension and high cholesterol and has a variety of associated nonspecific symptoms. “They're following the blood pressure, the diabetes, the cholesterol, their weight, their mental health, and to add this in may not be the most realistic thing,” she said.

Because of that, Dr. Dream welcomes referrals, even just to have a more detailed conversation. “There is a high threshold to refer, especially to an endocrine surgeon, because people don't want to refer unless they think that patients are going to have surgery,” she said. “We're always happy to have to see patients and just have a conversation with them, even knowing that they might not need surgery yet.”

Surgical, medical options

Parathyroidectomy can take about 20 to 30 minutes, and the patient is able to go home the same day, explained Dr. Pasternak. In expert centers, the overactive parathyroid gland is identified through preprocedural imaging and is often taken out through minimally invasive methods. Afterward, he said, patients “actually feel like a fog lifted or they feel overall better and they're able to lead an objectively better life.”

Medical management options have been explored—calcimimetics or bisphosphonates, primarily—but these have not been shown to address the underlying primary hyperparathyroidism, only the symptoms, several experts said.

“It's not been found to be cost-effective to treat primary hyperparathyroidism medically because the problem never goes away,” Dr. Stack noted. “Surgery cures the problem. Medicine just treats the problem.”

That said, Dr. Dream acknowledged that not all patients want to undergo surgery and would prefer to be monitored long term. For this group, internists can conduct follow-up at least yearly with lab work, a DEXA scan, and a 24-hour urine calcium test as well as reassessing surgical options, she said.

While the risks associated with parathyroidectomy are minimal, Dr. Ganesan said, “if someone's very, very old, perhaps the risks may outweigh the benefit. In that decision process of whether the patient is up for surgery, ready for surgery, those types of things matter and would be in the internist's hands to help decide.”

Looking at the bigger picture of prevention and treatment, Dr. Stack hypothesizes that there are links with diet and lifestyle. His recent study, published in December 2021 in Head & Neck, used machine learning to predict primary hyperparathyroidism with 86% accuracy using elements from electronic medical records, such as diabetes and BMI, but not knowing calcium or PTH.

“The fact is that we're seeing this disease migrate into the developing world as they take on more of a Western lifestyle,” he said. “My goal would be to be able to educate physicians and ultimately patients … that if you live a life where you're obese for an extended period of time, 20 to 30 years, you may be putting yourself at risk for primary hyperparathyroidism.”