Be on alert for CRC in younger patients

Medical groups are coming to consensus about expanded screening guidelines for colorectal cancer that lower the age to begin screening.

New guidance recommends screening younger adults for colorectal cancer (CRC) amid recent upticks in CRC incidence and mortality in this population.

In May, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) expanded the recommended age range for CRC screening in average-risk adults to 45 to 75 years in an update of its previous 2016 recommendation, which recommended screening starting at age 50 years. The recommendation is grade A for adults ages 50 to 75 years and grade B for those ages 45 to 49 years. (The Task Force also has a grade C recommendation to screen selected patients ages 76 to 85 years, depending on individual circumstances.)

“The main change from our prior recommendation is recommending the starting age of 45, rather than 50, and that's important because we think additional lives can be saved,” said Michael J. Barry, MD, MACP, vice chair of the USPSTF.

Several medical groups are coming to a consensus on this issue. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network both updated their recommendations in 2021 to start screening average-risk patients at age 45 years. In addition, the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, which is made up of representatives from the ACG, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, sent out a member alert in May stating its strong support for the USPSTF recommendation, noting that it is also finalizing its own recommendation to lower the age to start screening to 45 years.

That being said, the data are stronger to support beginning screening at age 50 years. ACP's most recent guidance statement on CRC screening, published in November 2019 by Annals of Internal Medicine, recommended that clinicians screen for CRC in average-risk adults between the ages of 50 and 75 years. The guidance attempted to reconcile existing guidelines, including the American Cancer Society's 2018 guideline that included a qualified recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years in addition to a strong recommendation to screen adults ages 50 years and older, noted Michael P. Pignone, MD, MPH, MACP, in an accompanying editorial.

“Cost-effectiveness analyses support a qualified recommendation to adopt an earlier starting age for screening only if the screening rate in persons aged 50 to 75 years is already high (>80%). … As we consider how best to proceed at the margins, it is important not to lose sight of the strong consensus supporting screening for this age group,” Dr. Pignone wrote.

Internists are integral to implementing CRC screening across the spectrum of ages, said Dr. Barry, who is also a primary care general internist and director of the Informed Medical Decisions Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, as well as a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“Even for people 50 and older who we had previously recommended screening for, we think perhaps a quarter or so of those folks have not been screened,” he said. “So we've got plenty of work to do in the 50- to 75-year-old age group, but there's additional work now for people starting at age 45.”

Early-onset CRC increasing

CRC is a major problem in the U.S.

In 2019, 51,896 people died of CRC, which was the No. 2 leading cause of cancer death in both men and women, second only to lung and bronchus cancer, according to CDC data.

As screening increased, rates of CRC decreased among all patients ages 50 years and older over the past 20 years; however, the numbers aren't so rosy for those on the younger side, according to the American Cancer Society's CRC statistics, published in March 2020 by CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. From 2011 to 2016, incidence rates rose by 2.2% per year in people younger than age 50 years and by 1% per year in those ages 50 to 64 years. From 2008 to 2017, mortality rates increased by 1.3% per year in those younger than age 50 years.

Due to the changing epidemiology of CRC, about 10% of CRC cases are now diagnosed before age 50 years, said Dr. Barry. In adults ages 40 to 49 years, incidence of CRC increased by nearly 15% for adenocarcinomas, the cancers targeted by CRC screening and surveillance, from 2000-2002 to 2014-2016, according to a study published in the February Annals of Internal Medicine.

“That was the first study to look at adenocarcinoma specifically, because prior studies pooled carcinoids and adenocarcinomas together,” said senior author Jordan J. Karlitz, MD. “In that paper, we confirmed that adenocarcinomas are primarily driving the increase in early-onset colon and rectal cancer rates we are seeing. We thought this was important information supporting the rationale to decrease the screening age to 45.”

Another recent study, published in June by JAMA Network Open, provided more evidence that people under age 50 years will benefit from routine screening.

“We found that while people diagnosed before age 50 generally have poorer survival than older patients, that difference can be largely explained by the fact that they are diagnosed at a later stage. When we adjusted for the stage of cancer at which a patient is diagnosed, younger people fared slightly better in terms of survival,” although the difference was small, said senior author Charles Fuchs, MD, MPH, FACP.

In another study, Dr. Karlitz and his research group looked at CRC incidence rates in one-year age intervals.

“We wanted to see what happened between the ages of 49 and 50 … when large segments of the population have historically entered screening protocols,” said Dr. Karlitz, who is chief of the GI division at Denver Health Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, Co.

The increase was steep. During the age transition from 49 to 50 years alone, there was a 46.1% increase in CRC incidence rates, according to results published in January 2020 by JAMA Network Open. Overall, about 93% of CRC lesions diagnosed at age 50 years were invasive, or beyond in situ stage, indicating that a large number of previously undetected preclinical cancers were first diagnosed when patients began screening at age 50 years.

“In our study, we estimated that from 2000 to 2015 … there were approximately 129,000 cases of colorectal cancer in the U.S. among those between ages 45 and 50,” said Dr. Karlitz. “That's a lot of cancers in just that small age group between 45 and 50. Obviously, many of these cancers could have been completely prevented, or at the very least caught at an earlier stage of screening, if screening were to begin at age 45.”

In addition, there has been remarkable progress in treating CRC, with even more new advances on the horizon, noted Dr. Fuchs, who is the global head of hematology and oncology product development for Genentech, a U.S. biotechnology corporation.

“There is every reason to think people younger than 50 will benefit just as much from these advances, if they are diagnosed in a timely way.”

Another study, published in June by Gastroenterology, found that the rate of advanced colorectal neoplasia in individuals ages 45 to 49 years was similar to that observed in those ages 50 to 59 years, suggesting that expanding screening to this population may result in earlier identification and surveillance of those at increased risk for CRC.

The results were not surprising to senior author Swati G. Patel, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCHealth Digestive Health Center and the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, as well as an associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, Co.

“This is likely because of a combination of 1) the ‘birth cohort effect,’ where younger generations are carrying increased risk with them, 2) advanced polyps take a long time to grow, and 3) there are likely many asymptomatic cancers and advanced polyps among those age 45 to 49 that are not diagnosed until an individual gets a screening test,” she said.

Regarding the birth cohort effect, CRC incidence did not begin to increase for adults younger than age 50 years until 1981 to 1985, according to results of a study published in May by Gastroenterology, suggesting that the increase may be attributable to risk factors that have been changing in recent birth cohorts.

Still, no one knows exactly why early-onset CRC is on the rise. While shifts in known risk factors for CRC, such as obesity, a Western diet, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, alcohol, processed meat, and others, could be driving up the CRC incidence in younger patients, more research is needed, said Dr. Karlitz. “We need additional studies to try and hone in on some of these factors in terms of how they might be driving the rates to go higher, including biospecimen analyses.”

Dr. Patel added that increasing incidence of early-onset CRC has also been observed in other Westernized countries, indicating that there may be associated risk factors contributing to the risk.

“Possibilities include sedentary lifestyles, early changes in the gut microbiome (from childhood antibiotics, antibiotics in the food chain, or increase in cesarean section deliveries), or even possibly ambient/water exposures that we are unaware of,” she said, adding that more research is under way.

In the meantime, there is plenty internists can do to confront the problem, said Dr. Fuchs. “Clinicians can be more rigorous in assessing family histories for younger patients. We also need to keep addressing the nation's obesity epidemic,” he said. “And we can close gaps by increasing screening and early detection of CRC, starting now at age 45.”

Practical considerations

Screening younger patients will be a challenge. Even in older age groups, up to a third of people who should get screened do not, and many of the barriers are at a systemic level and beyond the control of individual physicians, Dr. Fuchs noted.

“That said, primary care providers have an unmatched influence over a person's choice to be screened,” he said. “I would encourage them to be clear with patients that CRC cases are increasing in younger age groups—and that it is the second most common cancer in people under 50.”

The USPSTF doesn't recommend a specific screening test for CRC. But as Dr. Patel put it, and others agreed, “The best screening test is the test that gets done.”

Similarly, ACP's guidance statement recommends that clinicians select the CRC screening test with the patient on the basis of a discussion of benefits, harms, costs, availability, frequency, and patient preferences. “Clinical decisions on which screening test to use need to be individualized. As there is appreciable variability in patient values and preferences, you need to talk to your patient,” said Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, FACP, lead author of the guidance statement and Vice President of Clinical Policy for ACP.

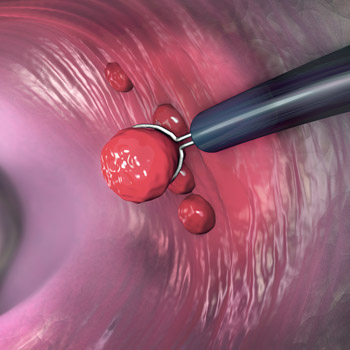

The Task Force recommendation includes a full menu of screening options, including stool-based testing (e.g., fecal immunochemical test [FIT], high-sensitivity guaiac fecal occult blood test, stool DNA test) and direct visualization testing (e.g., colonoscopy, CT colonography, flexible sigmoidoscopy). “All these tests need to be repeated periodically at different intervals over time,” with the stool tests needing to be repeated more often than direct visualization tests, noted Dr. Barry.

Thus, when deciding which test to use, patient adherence to the screening strategy, including any additional testing that's needed based on the results of the first test, is an important consideration. “With colonoscopy, we may be talking about, say, getting four colonoscopies over your life [at ages] 45, 55, 65, and 75,” said Dr. Barry. “Over that same period of time, if someone chose, for example, the FIT, we're talking about 40 tests over that period.”

Another benefit of colonoscopy is that it allows for the removal of precancerous polyps. But the invasiveness and associated risks are enough to make some patients more comfortable doing stool-based testing more often, he said.

“There's good evidence that offering more than one choice will increase colorectal cancer screening rates, so the best test is the one that the patient chooses and will follow through on,” Dr. Barry said, adding that patients should feel free to switch between screening modalities over the years if desired.

In Dr. Karlitz's clinic at Denver Health Medical Center, he sees a diverse patient population from a wide range of economic and racial backgrounds, including refugees from outside the U.S. “Since Denver Health is such a diverse system, it's really critical to be able to offer a variety of colorectal cancer screening options because people may have different perceptions and desires when it comes to screening,” he said.

The goalposts for CRC screening rates continue to shift. The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, an organization cofounded by the American Cancer Society and the CDC, proposed an initial goal for the nation to screen 80% of eligible adults by 2018, but that initiative fell short. In 2018, 68.8% of U.S. adults ages 50 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening, according to the CDC.

“Regular screening for CRC saves lives, so it is important for all of us to work together to increase the screening rate and reduce the cancer-specific mortality and morbidity associated with CRC,” said Dr. Qaseem.

In 2019, the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable announced a new initiative, 80% in Every Community, intended to reduce disparities in CRC screening rates across rural, low-income, and certain racial and ethnic communities. “Targeting these populations and understanding their barriers to screening could help us hit that 80% target,” said Dr. Karlitz, who serves as a member of the organization's steering committee.

Dr. Barry agreed that distributing screening across patient populations is important. Black individuals in particular are at higher risk of CRC and CRC mortality across the spectrum of ages. Black men are 24% more likely to develop CRC and 47% more likely to die of it compared to White men, and Black women are 19% more likely to develop it and 34% more likely to die of it compared to White women, according to data published in 2019 by the American Cancer Society.

“The evidence suggests to us inequities in screening may be the principal driver of that higher mortality, so I would call on my fellow internists to particularly get about screening for Black patients,” Dr. Barry said. “There are some other groups, like American Indians and Alaskan Natives, who are also at risk, so making sure that we distribute screening equitably across all our patients is really important.”

The cost of CRC screening is another important issue to consider. Dr. Barry noted that the Task Force doesn't make decisions with consideration of costs or insurance. “We just look at the evidence on the benefits, which are substantial here, and the harms, which are small but finite,” he said.

Although the Affordable Care Act links the Task Force's grade A and B recommendations to insurance coverage, there may be variability among payers, Dr. Barry said. “People should always have a conversation with their insurance companies about insurance issues related to this. Tests like colonoscopy can be relatively expensive, and knowing what their own coverage would be for the different choices would be reasonable,” he said, adding that patients who choose stool-based testing need to know that there is a small chance that they may have a suspicious test and will need a colonoscopy.

While the recommendation focused on CRC screening in asymptomatic patients ages 45 years and older, it doesn't apply to many at-risk patients who may be diagnosed at younger ages, noted Dr. Patel.

“Thus, it is extremely important that patients share their family history of CRC or advanced precancerous polyps, because those with a first-degree relative with CRC or an advanced polyp should start screening at age 40 or 10 years prior to their family member's diagnosis, whichever comes first,” she said.

Internists should also be vigilant about classic CRC warning signs in younger patients. Patients with early age-onset CRC have a greater delay from time of symptom onset to diagnosis (152 to 217 days) compared to individuals over age 50 years (30 to 87 days), Dr. Patel said.

“It is important to reinforce that CRC is not just an ‘old person’ cancer. … Any patient with symptoms such as rectal bleeding, changes in bowel patterns, unexplained abdominal pain, or iron deficiency anemia should be thoroughly evaluated, since these symptoms could be associated with CRC,” she said.

Finally, don't necessarily wait until age 45 to begin the conversation about CRC screening, said Dr. Karlitz. “I think if you bring it up gradually over time, before people actually reach the screening age, they may be more likely to undergo screening when it's offered at 45,” he said, adding that this strategy also allows the clinician to collect a family history in the interim.

Dr. Patel agreed. “I strongly advocate that we should bring up colorectal cancer risk and screening at the very first visit we have with a patient, no matter how old or young,” she said.