Making primary care more equitable

The Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) annual conference focused on creating a more equitable health care delivery system by increasing support, strengthening systems, and fixing disparities.

Primary care in the U.S. was in a precarious position before 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic has magnified its difficulties, said ACP's Executive Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, Darilyn V. Moyer, MD, FACP, during the Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) annual conference, held virtually on Nov. 30 and Dec. 1, 2020, and sponsored in part by ACP.

“COVID-19 has ripped open the seams of an already perilous health care system. As many have said, our health care system is neither about health nor truly a system,” she said. “While the terminology ‘primary care’ sounds like a simplistic type of care, those of us on the front lines know practicing primary care is anything but simple.”

Although primary care ideally focuses on maintenance of health, much of clinicians' energy is spent managing and caring for increasingly medically complex patients, said Dr. Moyer, who is also chair of the PCC board of directors. Meanwhile, the U.S. health care system's investment in primary care is low and declining, according to the PCC's 2020 Evidence Report findings, which were released in conjunction with the meeting.

From 2017 to 2019, primary care spending across commercial payers decreased from 4.88% to 4.67% of total national commercial health care spending, the report said. The majority of states also experienced a decline in primary care investment over this time period.

COVID-19 posed additional problems. Early on in the pandemic, the capacity of primary care practices to care for patients in novel ways was hindered by their reliance on fee-for-service payments, and less than half of the care provided by primary care practices in April 2020 was reimbursable, the report said.

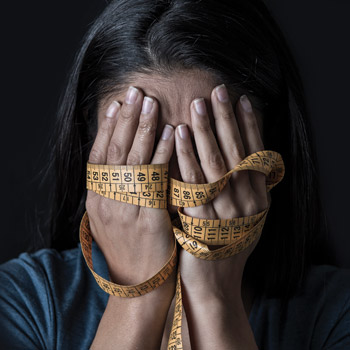

While these difficulties have been harmful to many primary care practices, Dr. Moyer highlighted another as primary care's greatest challenge. After 36 years of practicing medicine in communities facing the consequences of systemic racism, she is well aware of health disparities.

In addition to limited access to healthy foods and safe neighborhoods to exercise in, marginalized communities also have many essential workers who are un- or underinsured and cannot afford to miss work, let alone seek medical care, even if exposed to or ill with COVID-19, Dr. Moyer noted. “This has all led to a perfect storm to fuel the COVID-19 epidemic,” she said. “There is no easy fix here, and there is no vaccine for racism.”

The meeting's opening keynote presentation by Joseph Betancourt, MD, offered thoughts on creating a more equitable health care delivery system. He sees new enthusiasm for coming up with solutions to longstanding problems.

“Shortly on the heels of the coming down of our surge here in Boston in May was the murder of George Floyd, which I think put energy into a whole new set of conversations about the importance of equity that I hope we will never lose again,” said Dr. Betancourt, a practicing primary care internist and vice president and chief equity and inclusion officer at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston. “I would say that this time is exciting because it calls for meaningful change, executed with urgency, and primary care must play an essential role in this transformation.”

He offered the following lessons on COVID-19 and equity for health care systems:

1. Organizations must incorporate an equity analysis into emergency preparedness. “In this case, communities of color were hit early, they were hit hard, and they were in the perfect storm. How can we better anticipate that?” said Dr. Betancourt, who is also founder, senior advisor, and faculty of the Disparities Solutions Center at MGH.

2. Health care systems need to better incorporate race/ethnicity and equity measurement into all they do. “Surveillance, monitoring, dashboards, reports, big data serve as a springboard for action,” he said.

3. As systems redeploy for emergencies, they should make use of their staff members who speak languages other than English. For example, MGH created a registry of multilingual staff, Dr. Betancourt said. “And we created something called our Spanish-language care group when we saw that 40% of our COVID-positive patients were Spanish-speaking,” he said, adding that the group deployed 50 physicians who were fluent in Spanish to surge teams. “We always had a Spanish speaker with any Spanish-speaking patient to address the challenges that our interpreter services were facing in meeting those needs.”

4. As clinical care evolves, health care practices and hospitals must assure equity. Patient information should be provided in multiple languages, be presented at a level of low health literacy, and meet the needs of individuals with disabilities, said Dr. Betancourt. “As we go toward virtual health, how do we understand the impact of the digital divide, the limited cell service, and the cost of that around all these issues?” he said. “Minorities are less likely to be on our patient portal than their White counterparts. How do we think about equity here and in the use of the electronic health record?”

5. Make sure to care for staff members, too. MGH, which has a diverse staff, including in its nutrition and food services, environmental services, and materials management, launched a text messaging platform to democratize communication with employees, Dr. Betancourt noted.

6. Social determinants of health worsen during disasters and hasten spread during a pandemic. Health systems should take a “doorstep-to-bedside” approach by promoting wellness in their communities, he said.

He also shared the following lessons for primary care clinicians and practices:

1. Primary care must truly be a team sport. “This isn't just about the primary care doctor. This shouldn't be hierarchical,” Dr. Betancourt said. “We need to think about team-based care and execute team-based care in ways that we never have before.”

2. Meaningful access to care is essential. “An insurance card does not meaningful access make. … Ultimately, we need to build a system that focuses on the rational choices of patients and meet them halfway, not just think about what's rational to us as it relates to access to care,” he said.

3. Innovations should be applied equitably. “We can no longer afford to have a five- to seven-year innovation lag in vulnerable communities,” Dr. Betancourt said. “Virtual health, biometrics, precision medicine, therapeutics need to be deployed without that lag.”

4. Cross-cultural communication and trust-building are key. This includes “building trust around vaccines, around testing, communicating across cultures with trusted messengers so people don't get misinformation,” he said.

5. Awareness and avoidance of stereotyping are key to high-reliability care. “We have to think about unconscious bias and make that unconscious conscious every day,” said Dr. Betancourt, who is also an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

6. Diversity is not a “nice to have”—it is a “need to do.” “We need the courage to make those commitments,” he said. “I think the pandemic has demonstrated that.”

7. Ultimately, primary care cannot manage what it does not measure. “Maybe the least sexy of all this work is data, but data becomes the foundation upon which we can fundamentally say with certainty, ‘Yes, we are equitable,’” said Dr. Betancourt.