Understanding heart failure in African Americans

African Americans have a higher incidence of heart disease at a younger age, and they meet fewer criteria for ideal cardiovascular health, such as nonsmoking, physical activity, and lower body mass index.

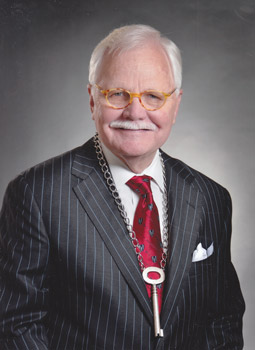

Is heart failure different in African Americans? Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, MACP, was tasked with answering this question in an opening plenary address at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, held in September in Philadelphia.

It's hardly a spoiler to reveal that his answer was yes. “There are real differences in the experience that African Americans have when they suffer heart failure,” said Dr. Yancy, a professor of medicine and medical social science and chief of cardiology at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago.

“There is a higher incidence of disease, particularly at a younger age. The likely culprit is not ischemic; hypertension is implicated now as perhaps a causative circumstance, and there is, we believe, a predisposition for ventricular remodeling. These statements have been articulated many times over the past 20 years and reflect our ground truth,” he explained.

Research has also shown that African Americans meet fewer criteria for ideal cardiovascular health, such as nonsmoking, physical activity, and lower body mass index, than whites in the U.S. “Arguably, this absence of variables that are associated with health predisposes to disease,” said Dr. Yancy.

Hypertension is a marker of poor cardiovascular health, of course, and studies have shown that it's also more likely to lead to heart failure in African Americans. “When adjusted for the duration or burden of hypertension, there is still an excess signal of ventricular thickness and an increase in left ventricular mass when compared to whites with the same burden of high blood pressure,” said Dr. Yancy, citing a 2004 study in Hypertension. “The response to this ordinary risk of hypertension is exaggerated and more deleterious in African Americans.”

Geographic studies of heart failure in the U.S. have also highlighted the disproportionate incidence in this population. “It exactly parallels the traditional stroke belt as well as major urban cities, areas that are heavily populated by African Americans,” said Dr. Yancy. “There is an intense concentration of heart failure in these areas of the country where African Americans live.”

What's new are some possible explanations for all these findings. The African-American Heart Failure Trial showed in 2004, with results published in the New England Journal of Medicine, that isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine reduced mortality in black patients. But then the investigators went on to discover more.

“The investigators of the African-American Heart Failure Trial were one of the first investigatory groups that prospectively established a genetic substudy,” said Dr. Yancy.

The research identified genetic variations related to nitric oxide that may help explain the higher burden of oxidative stress among African Americans. “Some differences in heart failure may be due to plausible biological and genetic differences,” summarized Dr. Yancy.

But it's not just about genes; there have also been recent discoveries about the role of the exposome. “We're learning that the things to which we respond in our environment may have a unique impact on our health,” said Dr. Yancy.

Specifically, in heart failure, phosphate may be an important factor. And it's common in preserved foods, said Dr. Yancy, who offered canned blueberries, frozen broccoli, and deli versions of roast beef and chicken as examples. “If you take these healthy foods and simply preserve them, you increase the inorganic phosphate content by 51%,” he said.

That's a problem because researchers are finding associations between inorganic phosphate consumption and heart failure, both in mice and in humans. It appears to relate to a hormone called fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23).

“In a linear fashion, where FGF23 levels are increased, we see significantly more hypertension,” said Dr. Yancy, citing a study he coauthored that was published in the July 2018 Hypertension. More recently, his research has taken the next step, finding a relationship between higher FGF23 concentrations and a significantly increased risk of heart failure, in results published in the American Journal of Hypertension in January.

“What we've since identified is a striking increase, specifically an association—not causal—with heart failure. After doing multiple adjustments, we've identified a 63% increased risk in the presence of heart failure when we see hypertension and increased FGF23,” Dr. Yancy said.

This could significantly change thinking about heart failure in African Americans, he explained. “That gets us to this point: We believe that in certain at-risk communities, exposure to a diet very high in inorganic phosphates (processed foods) leads to upregulated production of FGF23, leading to cardiac hypertrophy, made worse in the presence of chronic kidney disease, and subsequent clinical heart failure—perhaps providing an alternative explanation for disparities that have been classically described as either inexplicable or due to race only.”

It's not the only new explanation, though, Dr. Yancy noted. Other recent research, published in the July 2 Journal of the American College of Cardiology, has uncovered a neurobiological pathway that may explain how social determinants of health connect to cardiovascular disease.

“There is a link between crime, segregation, poverty—all the things that constitute adverse social determinants of health—which may predispose to cardiovascular diseases,” he said.

And then there's a possible and sobering link to health policy. Heart failure-related death in the U.S. rose between 2012 and 2017, after decreasing from 1999 to 2012, according to research published as a letter in the May 14 Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The fact that the direction changed in 2012 raises the concern that readmission penalties may have been a cause, Dr. Yancy noted. “Is this an unintended consequence of health policy?” he asked. “These kinds of observations cannot be ignored.”

The study also showed that black men and women had consistently higher heart failure-associated mortality than white men and women. “If we look at age-adjusted mortality rates from heart failure as a function of gender and race, particularly for persons less than the age of 64, we see this unique signal,” he said. “All lines are trending toward an increase, but uniquely so in African Americans.”

All of these data lead to an answer on the question of Dr. Yancy's lecture—whether heart failure is the same in all patients. “I would say without hesitancy that no, everyone is not the same,” he said. “But is it because of race? Perhaps it's because of epidemiology that affects some people currently described by race. Perhaps it is because of the worsening influence of certain social factors. Almost assuredly genomics and genetic ancestry has something to do with it, and that's highly variable.”

Physicians need to keep this complexity in mind when caring for patients, Dr. Yancy advised. “What is the takeaway or what is operational today? We should all check our assumptions at the door and not use stereotypes to define disease,” he said. “Differences in heart failure that we have traditionally ascribed to race I think need to be revisited. Race as a biological construct is a non sequitur. Persistent discussions that imply race only allow us to introduce bias and halt our progress.”