MKSAP Quiz: Acute onset of vision loss

A 64-year-old man is evaluated in the emergency department for acute onset of vision loss in the left eye, which began 1 hour ago.* He can barely see his own hands in front of his eye. He has no eye pain. One week ago, he had an episode of monocular vision loss in the left eye that resolved after 5 minutes. He has had no other recent medical concerns. He has no history of floaters, headaches, jaw claudication, muscular weakness, or weight loss. Medical history is significant for hyperlipidemia and hypertension. Medications are atorvastatin and lisinopril.

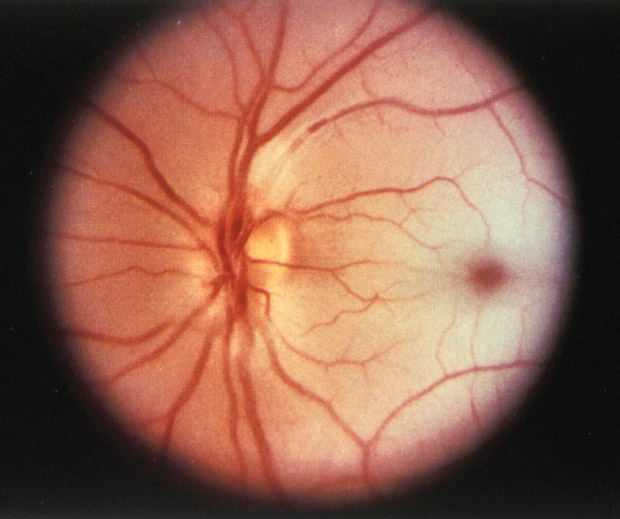

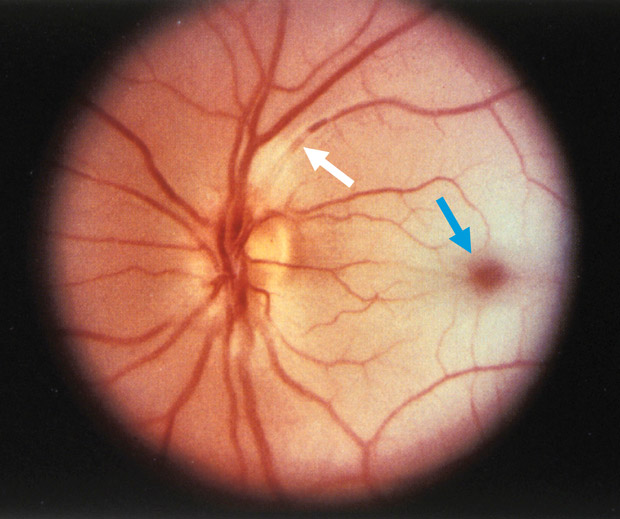

On physical examination, vital signs are normal. There is loss of visual acuity in the left eye, and pupillary examination reveals an afferent pupillary defect. The optic disc is shown. There is no conjunctival erythema or scalp tenderness.

Laboratory studies reveal an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 22 mm/h.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Acute angle-closure glaucoma

B. Central retinal artery occlusion

C. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

D. Retinal detachment

Answer and critique

The correct answer is B. Central retinal artery occlusion. This item is Question 76 in MKSAP 18's General Internal Medicine section.

The most likely diagnosis for this patient's painless visual loss is central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). This patient has several risk factors for this condition, including advanced age; male sex; and associated cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Examination reveals an afferent pupillary defect and cherry red fovea (blue arrow) that is accentuated by a pale retinal background. Interruption of the venous blood columns may be recognized with the appearance of “boxcarring” rows of corpuscles separated by clear intervals seen in the vein just superior to the optic disc (white arrow). The most likely cause in this case is carotid atherosclerosis, but CRAO may also be caused by cardiogenic emboli; carotid artery dissection; hematologic conditions, such as sickle cell disease; or hypercoagulable states. The occlusion may be preceded by transient visual loss or a stuttering course. Retinal examination may demonstrate emboli. In an older patient who lacks emboli on examination, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level should be obtained to rule out giant cell arteritis, which is a rare but important cause of CRAO. Prognosis is based on visual acuity at presentation. Ischemia that lasts 4 hours or longer tends to result in irreversible vision loss. Treatment may include measures to lower intraocular pressure. Emergent ophthalmology consultation is required.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma typically presents with severe eye pain and visual loss. It may involve headache, nausea, and vomiting. Ophthalmoscopic examination reveals a mid-dilated (4-6 mm), nonreactive pupil and intraocular pressure greater than 50 mm Hg. This patient's clinical picture is not consistent with acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (previously known as pseudotumor cerebri) may present with diplopia, headache, and, most often, bilateral visual symptoms. These may include transient visual obscurations, which can be brief and triggered by body position change or the Valsalva maneuver. Papilledema is almost always present on examination.

Retinal detachment most commonly presents with photopsias (flashes of light); patients may also report seeing cobwebs and large floaters. Painless complete visual loss is possible, but retinal detachment is more often associated with progressive vision compromise that may involve partial visual fields. A horseshoe-shaped retinal tear may be observed on funduscopic examination.

Key Point

- Central retinal artery occlusion presents as acute, profound, and painless loss of monocular vision associated with an afferent pupillary defect and cherry red fovea.