Increasing colorectal cancer screening

Screening rates increased from 2000 to 2015 but continue to lag behind goal levels.

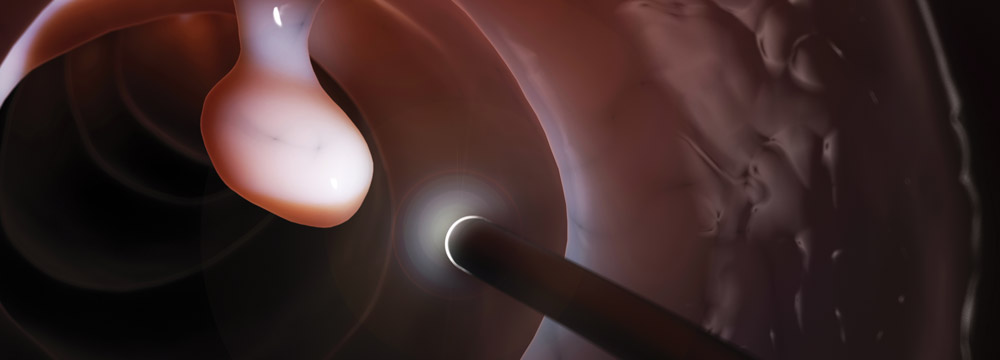

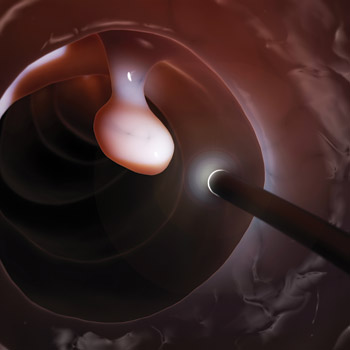

Perhaps more so than other preventive care, colorectal cancer screening has an infamous reputation. Ask a 50-year-old whether she has been screened, and she may well tell you no because the bowel prep sounds awful or she doesn't want someone looking “up there.”

But for all its invasiveness, screening patients for colorectal cancer works. As the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S., colorectal cancer presents a substantial preventable burden for both men and women, said David P. Miller Jr., MD, MS, FACP, professor of internal medicine and public health sciences at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“This is true with many cancers, but especially with colorectal cancer, if you wait to diagnose it until the patient has symptoms, it's generally too late,” he said. “It's really difficult to cure once it is symptomatic and being diagnosed at a symptomatic stage.”

In addition to catching colorectal cancer early, the screening cascade, including polypectomy, can prevent cancer from ever developing, Dr. Miller added. “This is a stark contrast to other screening tests we do, like mammography. … We're not preventing women from getting breast cancer; we're finding it early and we're treating it early,” he said.

Despite the well-known benefits, overall screening rates in the U.S. have yet to meet goals set by national initiatives. To increase screening uptake, internists can do more than opportunistic patient education and encouragement, experts say. Researchers and, increasingly, health systems are addressing challenges, reaching out to patients outside of the clinic, and aiming for a world where getting screened for colorectal cancer is the easy choice, not a pain in the backside.

Addressing challenges

While colorectal cancer screening rates increased from 2000 to 2015, according to the CDC, they continue to lag behind goal levels.

In 2008, 52.1% of adults ages 50 to 75 years were screened for colorectal cancer based on the most recent guidelines, according to age-adjusted data from Healthy People 2020. The target goal is 70.5% by 2020, and the most recent CDC estimates indicate that progress is slow. As of 2015, 62.4% of men and women reported colorectal cancer screening test use consistent with U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations, the CDC reported in August 2017 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).

At the end of 2018, the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable changed the name of its 80% by 2018 Pledge initiative to the 80% Pledge. Despite removing time constraints from its goal, the organization cited pockets of progress, including numerous examples of health systems and commercial health plans that achieved screening rates of 80% or higher.

But more than a third of U.S. patients are still not getting screened for colorectal cancer. Hispanic patients, those who are uninsured, and those who have been in the country fewer than 10 years have lower rates of screening than other populations, according to national data in the August 2017 MMWR.

Many challenges contribute to a low overall screening uptake. One practical example is present-time bias, said gastroenterologist Shivan J. Mehta, MD, MBA, MSHP, an assistant professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “People favor things today as compared to things in the future, and that's why many people don't participate in prevention activities,” he said.

Logistically, a successful screening cascade has many steps. First, clinicians and patients need to know who is eligible for screening. Next, patients need to be screened in a way that doesn't require too many extra steps. “And then they actually have to follow through with the screening activities,” said Dr. Mehta. “I think there are probably some gaps in each of those steps of the process.”

Particularly in complicated contexts like this, people also have status quo bias, which means they are more likely to stick with whatever decision is the default, he said. Historically in the U.S., colonoscopy is the default screening test in most populations, said Dr. Mehta. But fortunately for tentative patients, it is far from the only screening choice.

In its 2016 grade-A recommendation for colorectal cancer screening in average-risk adults ages 50 to 75 years, the USPSTF listed several options for screening strategies: colonoscopy every 10 years, flexible sigmoidoscopy every five years, annual fecal immunochemical test (FIT), annual guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT), multitarget stool DNA test every one or three years, computed tomography colonography every five years, and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years plus FIT every year. The USPSTF did not prioritize any of the screening tests over the others.

To examine status quo bias in the setting of colorectal cancer screening, Dr. Mehta led a study that randomized patients to either opt in or opt out of mailed FIT outreach. About 10% of patients who were asked to participate in the program completed their FIT, compared to about 29% of those who were automatically enrolled but given the choice to opt out, according to results published online in June 2018 by the American Journal of Gastroenterology. “By switching that default from opt-in to opt-out, you can dramatically increase participation,” Dr. Mehta said.

Despite being the default choice for most, colonoscopy presents a variety of obstacles, such as fear or lack of awareness around the procedure itself, as well as the need for patients to take off work and find an escort to the appointment, noted Gloria D. Coronado, PhD, a scientist in health disparities research at Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore. Providing screening options other than colonoscopy can help increase uptake, especially in traditionally underscreened populations, she said.

“Certain tests are more acceptable to populations than other tests,” said Dr. Coronado. “In research that's looked at how likely a person is to complete screening if they're offered a free FIT test or a free colonoscopy or usual care, the data show that more patients will get screened if they're offered FIT testing.”

Of course, there are also financial barriers, particularly in uninsured and underinsured populations. One system-level change that could improve screening rates is the Affordable Care Act (ACA), whose main provisions went into effect in 2014 and would not be fully reflected in 2015 data, Dr. Miller noted. Under the ACA, insurers must cover preventive services with no cost to the patient if the services hold grade-A or grade-B recommendations from the USPSTF. “There is reason to hope that will bump up screening, since it has removed the financial barrier—for everyone who has insurance, anyway,” he said.

What works?

Health systems have several evidence-based options to increase screening uptake.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 73 randomized trials, the interventions that were most associated with increased colorectal cancer screening completion rates compared with usual care were fecal blood test outreach (risk difference, 22%) and patient navigation (risk difference, 18%), followed by patient education and patient reminders, which had risk differences of 4% and 3%, respectively, according to results published in October 2018 by JAMA Internal Medicine.

In general, usual care was typically visit-based opportunistic screening, and while mailed FIT outreach is increasingly used by systems such as Kaiser, it is still not widespread, noted senior author Daniel S. Reuland, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

“At our academic practice that serves a lot of uninsured patients, we do a lot of FIT testing, and we also do mailed reminders,” he said. “We haven't actually mailed the FIT tests. We're going to start doing that … but it's challenging to implement these things.”

Another challenge with stool testing is that it is ideally performed every year. Most clinics do a colonoscopy-first approach because they are not structured to offer FIT as the default choice, noted Dr. Mehta. “In order to effectively do a stool-testing strategy as a primary strategy, you need to have mechanisms to be able to reach out to patients every year,” he said. However, Dr. Reuland added that “There's some evidence that doing biannual stool testing reduces mortality; you just don't get as much effect as you do if you get it done annually.”

Most Kaiser Permanente regions have adopted centralized programs that directly mail FIT kits to patients, said family physician Beverly Green, MD, MPH, a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute and Kaiser Permanente Washington in Seattle. These programs have led to some of the highest colorectal screening rates in the U.S., as well as consistent adherence to annual screening, she said.

However, clinic staff may not be able to implement mailed programs as effectively because of competing demands for their time, Dr. Green noted. One way to relieve the burden on individual clinics is using a vendor to do the mailings, she said. “We've encouraged that approach because in a study we did with safety-net clinics, we found that clinics were somewhat challenged to be able to implement the mailed program on their own because they had competing priorities,” said Dr. Green.

Another downside to FIT is that if a patient tests positive, he must go through with a follow-up colonoscopy, which is a barrier for many and can lead to dangerous delays.

In federally qualified health centers, only about 50% to 60% of patients who have a positive FIT will go on to get a follow-up colonoscopy, reported Dr. Coronado. “Those percentages are unacceptably low because we know patients who have a positive FIT test result have about a one in 20 chance of having colon cancer,” she said. “For patients who have a positive FIT result and do not get a follow-up colonoscopy, the benefit of FIT screening is nullified.”

In addition, the more time that passes between a positive FIT result and follow-up colonoscopy, the higher the risks of colorectal cancer and advanced-stage disease, according to a study published in October 2018 by Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Compared with colonoscopy within one to three months of a positive FIT, the odds of either outcome increased after a delay of six months and even more so after a delay of 12 months, the study found.

At Kaiser Permanente, Dr. Coronado's research team is using risk prediction modeling to identify patients who have the lowest probability of getting a colonoscopy on their own and then delivering patient navigation to those patients. Patient navigation interventions come in a variety of forms, such as telephone follow-up from a nurse or other health professional.

“Navigators make a series of contacts with the patient to address the logistical, emotional, and informational challenges they may encounter that keep them from getting a colonoscopy,” said Dr. Coronado. Sound expensive and time-consuming? It is. As Dr. Green put it, patient navigation is resource intensive, “But so is colon cancer.”

One final downside of FIT outreach is that while initial screening for colorectal cancer is covered by insurance under the ACA, there may be costs to a patient who has a follow-up colonoscopy after a positive FIT, said Dr. Reuland. “We need better and more consistent payment policies that ensure coverage of colonoscopy after an abnormal FIT test,” he said.

At Kaiser Permanente Washington, patients who complete a FIT generally have no out-of-pocket costs, said Dr. Green. But this is not always true, depending on the type of insurance plan, she said. The state of Oregon recently passed legislation that requires commercial insurers to cover the cost of colonoscopy in full after a positive FIT, Dr. Green noted, adding that in most states, Medicaid also covers colonoscopy with no patient out-of-pocket costs.

Another finding from the recent systematic review in JAMA Internal Medicine is that interventions with multiple components are more effective than single-level interventions. One example of a multilevel strategy is a digital health intervention at Wake Forest that centers around a mobile app, said Dr. Miller. The intervention targets patients by educating them about colorectal cancer screening and also targets the system by letting patients order the screening themselves, removing the need for doctors to do so, he said. After tests are ordered, automated text messages provide follow-up support to patients.

In a randomized trial published in April 2018 by Annals of Internal Medicine, screening rates were 30% in the group who used the app compared to 15% in the usual care group.

“Where the intervention didn't do as well as we hoped is in terms of the percentage of ordered tests that patients completed,” said Dr. Miller. “Overall, patients completed only roughly half of the screening tests that were ordered, so that's the next place where we're focusing our efforts.”

In a randomized trial, Dr. Reuland and colleagues tested another example of an multicomponent intervention, with results published in July 2017 by JAMA Internal Medicine. The intervention, designed to improve screening in a diverse, vulnerable patient population, combined a colorectal cancer screening decision aid video (shown to patients on an iPad before their primary care doctor visit) with patient navigation support for test completion after the visit. Screening completion rates were 68% in the intervention group, compared to 27% in the usual care group.

What's next?

Looking forward, it is easy to see that more technology-based screening interventions will arise. “Leveraging tech to help us deliver preventive health services is low-hanging fruit,” Dr. Miller said. What remains less clear is exactly how to implement such strategies.

In a new study, Dr. Miller and his team are implementing the app-based intervention in 28 primary care practices in the Southeast (and are anticipating better results with all of the clinics using the FIT versus the more cumbersome FOBT). To figure out how much support clinics really need, the study will randomize clinics to either a “low-touch” or a “high-touch” implementation strategy, he said.

When thinking of implementation within health systems, context is an important consideration, said Dr. Reuland. What makes sense for an integrated system serving employed, insured, mostly white people in Seattle may not make sense for a community health center in rural North Carolina, he said.

“Internists should think of themselves not just as individual actors caring for individual patients but also as architects of a system that provides population health in the context you're working in,” Dr. Reuland said. “That context is not going to be the same everywhere, especially in the U.S.”

One strategy that has had mixed results in different contexts is offering patients financial incentives to complete screening, said Dr. Mehta, who is also associate chief innovation officer for Penn Medicine in Philadelphia. “How that financial incentive is designed can impact if it works or not,” he said.

In one study by his group, published in the November 2017 Gastroenterology, offering a $100 incentive to health system employees doubled participation in screening colonoscopy. On the flip side, a study that Dr. Mehta presented in October 2018 at the American College of Gastroenterology meeting compared mailed FIT outreach with three different financial incentives that were each $10 in value and found that they made no difference.

“None of those three financial incentive arms of equivalent value actually had greater response rates than just the routine mailed outreach with no financial incentives,” said Dr. Mehta. However, he noted that a high response rate to the mailed FIT alone may have prevented the financial incentives from having more of an impact.

Whether or not financial incentives work, deploying proactive strategies that leverage technology to make communication more efficient outside of office visits will help bridge the screening gap, said Dr. Mehta. “Technology is important because we can do things like text messaging and use secure messaging portals to also send outreach to people at a very low cost in a very easy way,” he said.

Most primary care practices are currently using a reactive visit-based model, but there is an opportunity to redesign practices and increase screening rates by using tools and staff that are already available, said Dr. Mehta. “In the future, you can imagine us being more proactive about it and leveraging teams in the system to do all of the outreach,” he said. “We should allow nurses and medical assistants and population health managers to be able to engage with patients for a lot of these activities.”

As Dr. Miller sees it, progress in colorectal cancer screening uptake will require big changes on a systems level, rather than on an individual physician level. “Until we have some significant change in the way we're systematically delivering care, I don't anticipate seeing a big difference in colorectal cancer screening rates,” he said.