Details debated in breast screening

Amid a thicket of competing and sometimes conflicting studies about breast cancer screening, medical groups have adopted differing stances on how to address the conundrum of harms versus benefits.

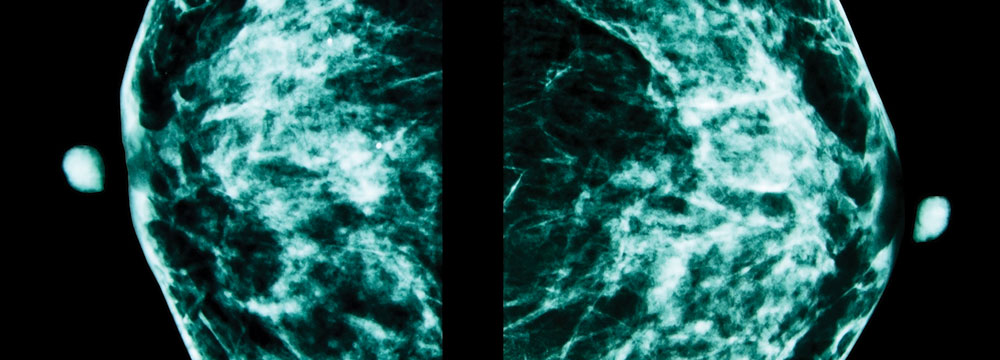

A mammography study published in January highlighting the risk of breast cancer overdiagnosis added more fuel to the ongoing debate over the increasingly complex and highly personal decisions surrounding breast screening.

The heart of the discussion involves an inexorable dilemma: how best to maximize the benefits of earlier breast cancer diagnosis without unduly setting up women for other harms? The recent Annals of Internal Medicine study, published online on Jan. 10, reported that as many as 38.6% of invasive breast cancers were likely overdiagnosed.

Overdiagnosis is the detection of subclinical disease by screening that would either not progress or would progress so slowly that it would never threaten the life of the person within that person's lifetime. Researchers' efforts to quantify overdiagnosis rates have yielded widely varying results to date, according to Joann Elmore, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine who practices medicine at Seattle's Harborview Medical Center. But the risk of overdiagnosis is real, and it becomes more likely with increased screening frequency.

“The more we screen, the more we find these overdiagnosed cancers,” Dr. Elmore said. “And the question is, how do we know whether a particular cancer is overdiagnosed or not? We don't. I think it's understandable that when a woman is told that she has an invasive cancer, or even ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), the woman wants it cut out.”

All of the major guidelines are focused on women considered at average risk, without a close family member with breast cancer or genetic vulnerabilities, such as a BRCA mutation. Nearly 247,000 women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2016, according to National Cancer Institute data. But more screening also has boosted the rate of diagnoses of DCIS, sometimes dubbed stage 0 cancer. Once nearly unheard of, DCIS now comprises roughly one in four breast cancer diagnoses.

Amid this thicket of competing and sometimes conflicting studies, medical groups have adopted differing stances on how to address this harm-benefit conundrum.

In ACP's high-value guidance for cancer screening, published in Annals of Internal Medicine in 2015, the authors emphasized that the greatest overall mammography value is for women ages 50 to 74. Biennial screening should be encouraged in that age group and should be offered to women in their 40s, along with a discussion of benefits and harms, they wrote. Beyond age 75, or if a woman is believed to have a life expectancy of less than 10 years, mammography is not advised, according to ACP.

Among other medical groups, there is a mix of recommendations on when to start and how frequently to screen:

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, issued in 2016, place the strongest emphasis on women ages 50 to 74 getting screened every two years. They describe the overall value of mammograms in 40-something women as less strong and the decision as one that should be left up to the individual.

- The American Cancer Society's 2015 guidelines recommend annual mammograms for women ages 45 to 54, with screening in the early 40s dependent upon the woman's preference. After age 54, mammograms can be every two years and continue past the age of 74 as long as the woman's general health is good, with a life expectancy of at least 10 years.

- The American College of Radiology prefers an earlier start date, and frequent screening, recommending annual mammograms beginning at age 40. A woman should persist with screening through her later years as long as her health is good, with a life expectancy of at least 7 years, and she wants to continue.

The differing recommendations reflect to some degree what data are considered—sometimes randomized trials only and sometimes observational data as well—and how much relative weighting is given to the various benefits versus harms, said Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, FACP, Vice President of Clinical Policy for ACP. But the bottom line is that women, particularly those in their 40s, should be educated sufficiently to reach their own personal decision, recognizing that screening doesn't necessarily need to become a routine for everyone in this age group, he said.

“Women need to understand that screening is just not one single event,” Dr. Qaseem said. “Screening can lead to a cascade of events. We should avoid intensive screening strategies such as annual screening, or blanket screening everyone younger than 50 or older than 75 or even those with limited life expectancy, because the increase in harms is larger compared to the small benefit of screening.”

Debra Monticciolo, MD, who chairs the American College of Radiology's Commission on Breast Imaging, worries that how harms and benefits of screening are weighted, as well as how they are presented, might discourage some women from screening.

Regular mammograms can save lives, said Dr. Monticciolo, who practices at Baylor Scott & White Health in Temple, Texas. “There is no one who debates that, even the Task Force,” she said. In one recent meta-analysis she cited based on randomized studies and published in The Breast Journal in 2015, screening was associated with a 22% relative risk reduction in mortality.

But there are other benefits that some guidelines, such as the Task Force, do not include, Dr. Monticciolo said, most notably that earlier diagnosis can reduce the aggressiveness and side effects of treatment. The breast imaging specialist also questioned the use of the word “harm”—terminology used by the Task Force and the American Cancer Society guidelines—rather than referring to the “risks” of mammography. “I think it is intentionally pejorative,” she said.

Moreover, how does one quantify the benefit-harm ratio accurately, Dr. Monticciolo asked? Certainly some women prefer to avoid the anxiety associated with mammography, including follow-up testing, she said.

“But how do you weigh that against dying of breast cancer? Most women I think would say ‘Well, I would rather not die of breast cancer and I can take a little anxiety.’ I think women should be able to make that decision for themselves, to be offered a chance to maximize the benefit.”

Stratifying risks

The Annals analysis published early this year, which attempted to estimate overdiagnosis, looked at biennial screening and breast cancer rates in Danish women ages 50 to 69. Researchers found that screening mammography over 17 years did not measurably reduce the incidence of advanced tumors but significantly increased the detection of nonadvanced tumors and DCIS. Additionally, the rate of overdiagnosis associated with screening mammography, estimated using two different methodologies, ranged from 14.7% to 38.6% for invasive cancer and from 24.4% to 48.3% when DCIS cases were included.

This is a sizeable range in estimates, to be sure, and some are lower. Dr. Monticciolo pointed to a study published in 2013 in the BMJ, also based on mammography screening in Denmark, which identified an overdiagnosis rate of 2.3%. That risk can never be eliminated entirely, she said: “The only way to change the amount of overdiagnosis is to not be screened at all.”

Dr. Elmore would prefer less debating of the precise statistics and more effort to get women up to speed on the fact that mammography has some downsides. Ideally, women should be educated before they even begin screening, she said.

Walking a woman in her 40s through the decision to screen for breast cancer is particularly complex, Dr. Elmore said. The Task Force, in its guidelines, noted that the number of deaths averted by screening is lower in that age group and that the rates of false-positives and unnecessary biopsies are higher than among older women.

However, some evidence suggests that younger women are more likely to have faster-growing tumors, Dr. Elmore said. Plus, these women are more likely to have many decades of life potentially ahead, she said.

But that also means they have more years to cope with the potential harms from overdiagnosis, she said, “leading some women to have chemotherapy and mastectomies and end up with lymphedema, and end up labeled as a cancer survivor with increased surveillance for the rest of their lives.”

Another factor in which understanding is evolving is breast density and which women with dense breasts should undergo supplemental imaging following mammography, said Karla Kerlikowske, MD, an ACP Member and professor of medicine and epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Numerous states, at least 27 to date, have passed laws requiring women to be notified that they have dense breasts in case they want to pursue supplemental imaging. Dr. Kerlikowske has been involved with research indicating that breast density shouldn't be the only criteria to determine if supplemental imaging is indicated.

In meeting with women, Dr. Kerlikowske uses a risk calculator developed through the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium that incorporates a handful of questions, including breast density, to calculate a woman's risk of developing an invasive malignancy within the next five years. The findings can sometimes reassure women with dense breasts if they realize that they are not at above-average risk, she said.

Dr. Kerlikowske, who maintains that the field is moving toward more tailored screening, was involved in a model-based analysis that was published Nov. 15, 2016, in Annals of Internal Medicine. The study, using data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, attempted to identify optimum screening frequencies for women ages 50 to 74 based on breast density and risk.

When weighing harms and benefits, they determined that women considered at high risk who also have dense breasts could be candidates for annual mammograms. Meanwhile, women at average risk with low breast density could consider waiting as long as three years instead of two between tests, as that would reduce potential screening-related harms while not impacting mortality benefit.

Discussing values

Amid all of this back and forth, what's a primary care doctor to advise a woman, with numerous other medical issues to cover and just 10 minutes left in the visit? Various decision-making aids have been developed to provide women some visual depiction of the harm-benefit equation. But Dr. Qaseem was reluctant to recommend any in particular, saying that the aids can influence women in one direction or another, depending on the underlying data and how they are framed.

One recent study indicates that professional guidelines are influencing physicians' practice. Between 2007 and 2008 and 2011 and 2012, the rate of mammography referrals per 1,000 office visits declined by nearly 50% among family physicians and internists, according to the findings, published in November 2016 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. But among obstetricians and gynecologists, whose guidelines mirror ACR's recommendation for annual screening starting at age 40, the change in referral rate wasn't statistically significant.

Sometimes a doctor's recommendation also can stem from his or her patients' inherent biases, said Albert Fuchs, MD, FACP, a general internist based in Beverly Hills, Calif., who has a retainer practice with patients he said are eager to take any step to maximize good health.

Dr. Fuchs generally recommends annual mammograms starting at age 40, although he describes himself as sensitive to any misgivings that are expressed. But such concerns are rare, he said: “I think there is a lot more anxiety about catching cancer early than the potential harms of testing.”

If not careful, Dr. Fuchs added, a doctor can inflate a patient's fears in one direction or another. The physician could talk too much about breast cancer and thus drive the woman to mammography, he said. “Or I talk to you about overdiagnosis and make you irrationally afraid that you're going to have surgery and radiation for a breast cancer that's never going to hurt you,” he said.

No doctor wants to miss a single cancer that could make a difference for their patient's life, as well as their own malpractice vulnerability, said Dr. Elmore. She added that she is making an effort to educate women about the potential benefits and risks of screening when clinic time allows.

But that conversation can last several minutes even before broaching the concept of overdiagnosis, Dr. Elmore said. “I try, but I realize that it's not perfect. I think women deserve better. We need balanced decision aids to support our conversations and we need basic science to help us identify which cancers are actually going to progress and harm women and which are overdiagnosed.”

Dr. Qaseem said, “Talk to your patient, help them understand benefits and harms, as we all would place different weights based on our personal reasons and circumstances. In addition to other factors, there are variables that should be taken into account such as race and ethnicity. Remember, guidelines are guides to help clinicians with their judgment. If 10 to 15 minutes are not enough for the patient, provide written materials for the woman to review in advance or take home.”

He added, “Clinicians should help women and we should empower women to make a decision about getting screened or not. It should be an informed decision which is individualized rather being paternalistic telling women what to do.”