Facing depression in medical residency

Depression can be prevalent during medical residency, with long hours and social deprivation as contributing factors. Concerningly, the farther residents are into their training, the more depression rates rise. Some programs are delving into their trainees' psychological well-being.

Considering the countless stressors stacked up against resident physicians, recent research on the prevalence of depression in trainees produced a foreseeable outcome: About 29% have depression or depressive symptoms, a figure that has increased slightly over the past few decades.

Specifically, in 54 studies of more than 17,500 physicians in training, between about 21% and about 43% of trainees screened positive for depression or depressive symptoms during residency, according to a meta-analysis published in the Dec. 8, 2015, Journal of the American Medical Association. The prevalence of depression in residents increased by 0.5% per calendar year.

Of note, a subanalysis of 7 longitudinal studies showed a 4-fold increase in depressive symptoms during residency. “That's a very robust finding, and one that essentially proves that there's an exposure-outcome relationship here: Being exposed to residency results in an outcome of higher depressive symptoms,” said lead author Douglas Mata, MD, MPH, a first-year resident in pathology at Brigham and Women's Hospital and a clinical fellow at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

There are many possible reasons for developing depression in residency: long work hours and sleep deprivation, substantial student loan debt, patient deaths, and predisposition to depression. “You're taking a very highly selected group of very motivated people ... who are basically spending all of their waking hours working and may not have time to maintain healthy social relationships with family members and friends,” said Dr. Mata.

Although being a resident has been very difficult for a long time, many residency programs over the decades have failed to adequately understand the lives of both trainees and educators, said Kelley M. Skeff, MD, PhD, MACP, professor of medicine and co-director of the Stanford Faculty Development Center for Medical Teachers in California.

“I don't think [depression in residents] is a new problem, but I think it may well be exacerbated by new requirements, new accountability measures, [and] new tasks that need to be done that have taken away from some of the core activities that reinforce the gratification of being a physician and being a teacher,” he said.

Work-hour woes

Sleep deprivation is a major precipitant that may trigger depressive symptoms, particularly in those who are predisposed to depression, Dr. Mata said. “Depression, depressive symptoms, and sleep deprivation and disturbance are highly correlated with one another, and it's well understood that sleep deprivation is going to increase risk of having accidents,” he said.

Research shows that residents working traditional schedules with recurrent 24-hour shifts make 36% more serious medical errors than those whose scheduled work is limited to 16 consecutive hours, according to a 2007 report in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. Residents also suffer 61% more needlesticks and other sharp injuries after 20 consecutive hours of work, according to the report.

To help relieve the burden, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) limits resident duty to 80 hours per week with a minimum of 1 day off each week, averaged over a 4-week period, according to its 2011 Common Program Requirements. Duty periods are limited to 16 hours for interns, although more experienced residents may be scheduled to a maximum of 24 hours of continuous duty. The requirements state that residency programs must train all faculty and residents to recognize the signs of fatigue and sleep deprivation and educate them in alertness management. Strategic napping is encouraged, especially after 16 hours of continuous work.

In January, ACGME began a 2-phase review of these requirements, which will gather relevant data before updating the section pertaining to resident duty hours. Recommended revisions produced by the first review phase will be presented at a June meeting and implemented during the 2016-2017 academic year.

“The debate concerning resident duty hours, and to a lesser extent improvement in dimensions of the learning environment, reaches levels of intensity and emotion at least in part due to the fact that aspects of the discussion are ‘competing goods,’” ACGME CEO Thomas J. Nasca, MD, MACP, wrote in a January letter announcing the review.

Despite the best intentions of the work rules, residency programs interpret these requirements somewhat differently and are generally “not very creative in designing the work hours,” making it unclear whether residents benefit from the current requirements, said Robert Centor, MD, MACP, a professor of medicine and regional dean of the University of Alabama School of Medicine Huntsville Regional Medical Campus.

The Huntsville campus takes its own approach to work hours: To give residents more time to rest on days off, every other weekend is a “golden weekend,” which means they leave on Friday afternoon and don't have to return until Monday, said Dr. Centor, who is also immediate past chair of ACP's Board of Regents.

“They're working really hard, but they are looking forward to having that long weekend off,” he said. “You'll see them on Friday mornings pretty worn out, and then you see them come back on Monday morning in really good shape because they had all those days off.”

For the mandatory day off each week, many programs give residents a Tuesday off 1 week, for example, and a Thursday off the next, which doesn't offer as much stress relief as a free weekend, Dr. Centor said. “I've had a lot of residents agree with my opinion, but I know that I'm biased,” he said. “The bottom line is, we need to be more creative in how we schedule residents and students and make sure that they have some decompression time, which is really important.”

Diminishing the time at work may allow for more time outside, but the work itself may be becoming less gratifying—even if there is less of it, said Dr. Skeff. “I believe it is true that residents are trying to complete more work in shorter times, but simultaneously, the methods of patient care have changed,” he said. “With the advent of the electronic medical record [EMR], a method that is understandably supposed to improve documentation and communication, residents and practicing physicians are spending more time communicating with their computers, documenting what is needed for the business of medicine. Although potentially useful, this has, in fact, reduced the time for 2 major reasons why people chose to become physicians: the face-to-face caring for patients and the intellectual pleasure of studying and discussing the science of medicine.”

Knowing the signs

Educators and senior residents should be able to detect the signs of depression and substance use disorders in their trainees, such as not returning pages on time, lateness, or a sudden change in punctuality, said Morganna L. Freeman, DO, FACP, chair of ACP's Council of Resident/Fellow Members and chief oncology fellow at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla. “Our skillset as clinicians in paying attention not only to what patients say but what they don't say or how they interact with you is something you can easily carry over to how you interact with colleagues. ... We have to look out for each other,” Dr. Freeman said.

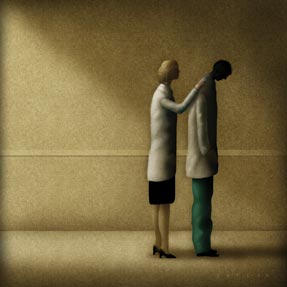

Educators can also put extra emphasis on empathy to establish a welcoming support system for trainees. “I think empathy is No. 1: to understand the focus is their health, not anything else, and, in many ways, to make clear that this is just another type of health issue, and if you had to be off for an infection, it would be the same thing,” Dr. Centor said.

As a senior resident on an ICU rotation, Dr. Freeman said she frequently saw residents struggle with the high stress and high workload and show subsequent signs of depression. In particular, she said she witnessed how the minute-to-minute clinical decisions and poor patient outcomes contributed to an “overarching sense of futility” in some trainees.

When an intern on her team would present with depressive symptoms, perhaps a lack of eye contact or an unwillingness to participate in rounds, Dr. Freeman said she found that the best approach to helping that trainee would be to wait until rounds were over, pull him or her aside, offer to take the next admission, and suggest a pleasant break, such as going outside for fresh air or getting coffee. In contrast, expressing concern in a more direct way, such as asking outright if a resident is depressed, hasn't produced as much success for Dr. Freeman.

“I think that indirect approach has been my most successful way to help trainees deal with it,” she said. “As educators, we have to be very sensitive to that and try to pay more attention to the nonverbal cues because it's very unlikely they will come to you and say, ‘I'm going through a tough time right now.’ That has maybe happened once in the entire time I've been in training.”

However, Dr. Freeman noted that, in her own experience as a chief resident, residents seem to be more comfortable with seeking help when program directors have a known “open-door policy.” One of the best ways to alert residents to an open-door policy is during intern orientation, which reviews all housestaff resources, including what is in place for residents who are stressed or need a sounding board, she said. “Every effort should be made to ensure what is discussed is kept confidential because there is still a stigma attached even to simple counseling,” Dr. Freeman said.

Chief residents and program directors should also meet regularly with housestaff to establish open communication, she recommended. “While part of our program's open-door policy was openly stated, a greater part of it was the culture of caring we had,” Dr. Freeman said. “We put a lot of effort into making our interns and residents feel comfortable enough to come to us with anything, and unless I had a visitor, my office door was always open.”

In addition, self-care may be an important skill to instill in residents. Dr. Mata said his medical school offered some talks on physician wellness, although he didn't think the subject was addressed as thoroughly as it could be. “I think they've gotten a lot better at it,” he said. “But awareness and training needs to begin on the first day of medical school.”

Faculty focus

Dr. Skeff added that programs should evaluate whether their teachers have time for observation and support of trainees and whether they are available and approachable so that trainees can tell them when they're having trouble. “My own sense is that many of us as teachers are not recognizing the depths of the challenge, the problems that the residents are feeling,” he said. “In some ways, this is a call for faculty development and a call for re-examination of where the teachers are.”

Even modest acts of kindness and empathy can have a major impact on trainees. “When I was a program director, to have done something as simple as bringing food in to the residents on a night when they were on call. ... To me, it was a simple task—an important 1—but to many of the residents, it was crucial to their recognition of being cared for,” Dr. Skeff said.

Another variable that programs should evaluate is the content of the residents' true curriculum, he added, noting that a resident recently reported that a major focus was on getting through the day, not adequately reflecting on the patient or the science of medicine. “We may want to ask whether or not the medical content we're teaching is content that remains exciting and reinforcing for the residents,” Dr. Skeff said. “Does it make them continuously excited about the science of medicine and about the humanism in medicine, or is what we're teaching now how to get through the day as efficiently as possible?”

Residents today are spending more time doing clerical work, such as charting in the EMR, and less time directly taking care of patients, Dr. Mata said. “I think there's been a lot of new barriers placed in-between the physician and the patient, and I also think there's been a progressive loss of autonomy in terms of the physicians' typical day-to-day role, and also the simple math of having too many patients to see and not enough people and time to see them all,” he said. “So your day just ends up being a constant blur of rushing ... without ever time to sit back and process what's happened.”

A major help may be hiring more ancillary staff and physician extenders, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and scribes who can help input data into the record, Dr. Mata suggested. “Anything that can take some of the secretarial burden off the residents and allow them to focus more on learning and taking care of patients than just on being a workhorse. ... A lot of times, the educational aspects are losing out to the more pressing demands of day-to-day work.”

The learning environment is another factor in depression because of its connection with trainees' stress levels, and teaching in a harsh or overly demanding way can create an unwelcoming environment for new doctors. In order to best instruct their residents, educators should check their egos, give positive feedback, and make sure that education remains the ultimate goal, Dr. Centor said. Although he engages in “pimping” by asking trainees questions, he said he does it in a nurturing way.

“I get away with it because it's clear that I'm just trying to get them to learn,” Dr. Centor said. “I say, ‘That's a good question because some people don't know, so let's learn more about it,’ versus ‘That's a good question; I sure fooled you.’ You're there to help the people under you grow; you're not there to enhance your own ego.”

In addition, educators should know their residents on a human level. “There is a tendency to have a little bit too much distance between the leadership and the learners, and you have to work hard to minimize that,” Dr. Centor said. “It's not that we're friends; it's just that they can trust me. It's treating people with respect. Too many medical students and residents are not treated with respect.”

Confidential support

On an individual level, educators can create a welcoming environment and help trainees struggling with depressive symptoms. But often, residents will resist getting help.

ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in internal medicine require program directors to monitor resident stress, including mental or emotional conditions that inhibit performance or learning, as well as signs of drug- or alcohol-related disorders. The requirements add that both program directors and faculty should know when to guide residents to confidential counseling and psychological support services.

To that end, residency programs adopt policies that separate trainees' mental health issues from their medical education. For instance, both of the University of Alabama's medical campuses direct depressed residents to mental health professionals who are not associated with the medical teaching program, Dr. Centor said.

“That's the right way to do it,” he said. “You don't want to do it in-house—that's a conflict.” When done right, referral to an outside clinician allows trainees to get the proper help in a nonthreatening way, Dr. Centor said. Stanford's residency program offers housestaff the opportunity to have confidential psychological support in the form of 10 visits with a psychiatrist, who serves as a career counselor of sorts, Dr. Skeff said, “because it's really true: They're into a tough career.”

For residents, confidentiality is a key factor in seeking help because of the stigma that depression is a sign of weakness, Dr. Freeman said. “People entering medicine are expected to be tough. We're expected to be objective. We're expected to take on these herculean tasks in order to get to some summit and some distant future that attests to the fact that we've made it,” she said. “And you don't get there unless you're tough and you don't break down and you don't allow these things to weaken you.”

During Dr. Freeman's residency at the University of Florida, a crisis office and a crisis hotline were made available to residents at any time of day, and they didn't have to worry about that confidential information showing up on their resident records, she said. “I think that was extremely reassuring because ... you didn't have to worry about people ‘finding out’ that you had a tough night or that you were really struggling with something, and then they would ensure some follow-up with you,” Dr. Freeman said.

Dr. Centor added, “There's always this fear that anything [residents] say or anything they do will get back to the program director and in some way impair their ability to get the right fellowship or the right job. ... You would think that as physicians, we're pretty good about discussing almost anything. We talk with our patients about almost anything. But it's different when it's a colleague, so we don't always do a great job. You try to realize that your goal is to help them as a human being, No. 1, and forget about your own internal conflict about what it means for the residency.”

Many times, this fear that having depression could interfere with one's completion of residency stems from belief and not necessarily fact, “but we're talking about people who are in a very emotionally vulnerable situation,” Dr. Centor said. “At the youngest, you're probably 26, and everybody else your age has a job ... and you're still trying to get through residency so that you can either get a fellowship or go out and get a job. And you're in huge debt, so you worry if you're going to be able to get a job and pay off your debts.”

Indeed, the profession is one of resilience and endurance. “We're supposed to be the tough guys. We made it through medical school. We deal with sick people every day. We see plenty of death. We see suffering,” Dr. Centor said. “And if we're having problems, then does that make us weak? Sometimes we have that perception, and there's a lot of fear about what this means to [residents]—not always rational fear.”