Diabetic foot care begins with bare feet

Internists can head up a care team that intervenes early and often in preventing the ulcerations, pressure points and neuropathies that can progress to infection and possibly amputation.

For David J. Aizenberg, MD, FACP, the first step in managing foot care for diabetic patients is simple: Start with bare feet.

“We try to have our medical assistants tell every diabetic patient to take off their shoes before the doctor comes into the room,” he said. “That little thing triggers the reminder that the physician should look at the patient's feet. Without that system in place, screening often falls by the wayside.”

Screening for foot problems is vitally important in diabetes, said Dr. Aizenberg, assistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and other experts. When built into routine care, it can mean timely awareness and treatment of the calluses, ulcerations, pressure points, and neuropathy that could potentially progress to full-blown infections and possible amputation.

Internists can help patients with calluses or pressure points avoid foot ulcers, and possible secondary infections, by recommending well-fitted walking shoes that provide cushioning and proper redistribution of pressure on the feet, according to experts. A referral to a podiatrist should be considered, and if there is lack of protective sensation, custom molded orthotics may also be beneficial.

Early recognition of foot infection is important, according to Benjamin A. Lipsky, MD, FACP, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle and visiting professor of medicine at the University of Geneva. Most diabetic foot infections can be cured, he said, but those that are improperly diagnosed or treated “often have devastating outcomes, such as lower-extremity amputation, which is associated with a five-year survival of less than 50%.”

The keys to prevention are early detection and aggressive control of blood glucose levels, according to John M.A. Embil, MD, FACP, a professor of medicine, infectious diseases and medical microbiology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. “But if infection occurs, an early aggressive approach is necessary to get the infection resolved and any open wounds closed,” he said.

Comprehensive exams key

The most common diabetic foot problems are infected foot ulcers, which present with signs of inflammation, such as redness, warmth, swelling, pain/tenderness, or purulent secretions and occasionally systemic symptoms of sepsis.

The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot, which issued its “Practical Guidelines on the Management and Prevention of the Diabetic Foot” in 2011, stated that patient and staff education, prevention of foot wounds, multidisciplinary treatment of foot ulcers should they occur, and close monitoring after treatment can lower amputation rates by 49% to 85%. The international group advises yearly comprehensive foot exams, and patients with demonstrated risk factors should undergo a brief inspection every one to six months.

“Every time I see a diabetic patient in my office, I make sure I am thinking that every diabetic is at risk for diabetic foot ulcers. I know that is not necessarily the case, but I make sure I am thinking about it,” said Dr. Aizenberg.

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), high-risk patients include those with:

- prior lower-extremity amputation,

- history of previous foot ulcers,

- peripheral neuropathy,

- foot deformity,

- peripheral vascular disease,

- visual impairment,

- diabetic nephropathy (especially patients on dialysis),

- poor glycemic control, and

- cigarette smoking.

Patients most at risk for infections are those who have no awareness of pain due to peripheral neuropathy and thus potentially no awareness of an early infection, according to Dr. Lipsky.

Whether a patient is high-risk or just a typical diabetic receiving an annual foot exam as recommended by the International Working Group and the ADA, the exam should include:

- inspection of the feet,

- assessment of foot pulses,

- testing for loss of protective sensation with a 10-g monofilament, and

- testing one of the following: vibration using 128-Hz tuning fork, pinprick sensation, ankle reflexes, or vibration perception threshold.

According to the International Working Group's position statement, the patient who cannot feel the pressure of a 10-g monofilament most likely has neuropathy and lacks protective sensation. The person may not feel even slight abrasions or foreign bodies in a shoe that can cause an ulcer. Additional examination with a tuning fork or pinprick can yield information about whether the patient is detecting vibrations or mild pain and discomfort.

Managing complications

If a patient doesn't feel it, and a physician doesn't notice it, a foot injury in a person with diabetes can become serious quickly.

“If the patient with diabetes and neuropathy develops a wound, the white blood cells may not function optimally and the infection will gallop along at a quite a rate,” Dr. Embil said. Patients realize they have a problem only when they start feeling unwell or have flu-like symptoms or when the wound begins dripping fluid or blood, and in some situations if a foul odor arises from the affected foot, he noted.

“The absence of pain is a very bad thing because the patient may perceive that as the absence of a problem and it may only come to the forefront when the situation is beyond salvation,” Dr. Embil said.

Decreased pain sensation can also increase the risk of skin breakdown and infections and also Charcot arthropathy, according to the ADA. Charcot arthropathy, a change in the shape of the foot as the result of fractures that go undetected, can be caused by trauma superimposed on a person with significant peripheral neuropathy. The acute Charcot foot can “look just like a skin and soft tissue infection,” he said.

According to an article about Charcot arthropathy by Dr. Embil in a 2009 issue of Nature Reviews/Endocrinology, the key to early diagnosis of Charcot foot in a diabetic patient begins with having a high index of clinical suspicion if the patient presents with new-onset swelling, erythema, and increased warmth of the foot and ankle with temperature variation between the two feet, as well as sensory neuropathy. Unlike patients with infections who may look and feel ill, these patients may feel well except for the local swelling and perhaps some pain. An initial radiograph may look normal, and MRI may help diagnose the condition.

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) also increases the risk of diabetic foot infections and complicates the treatment needed because of the underlying comorbidities. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) diabetic foot infection practice guideline states that patients with PAD have more severe infections, more nonhealing foot ulcers, and higher costs for treatment, which can include hospitalization and revascularization procedures.

The ADA recommends that patients be screened for PAD, including a history of claudication and assessment of the pedal pulses. In addition, a diagnostic ankle-brachial index should be obtained in any patient with symptoms of PAD. Much like neuropathy, PAD imposes a high risk of amputation and foot ulceration.

Treatment requires a team

The IDSA practice guideline recommends using a multidisciplinary team-based approach for both inpatients and outpatients with diabetic foot infections. (If a team is not available, the primary clinician caring for the patient's foot infection should attempt to coordinate the care among consulting specialists.)

A team implies that care is being given at an on-site facility such as a diabetic foot and wound clinic or academic teaching hospital, where there are several specialists on site. A diabetic foot infection can affect the skin, soft tissues, nerves, blood vessels and bone, Dr. Lipsky noted. Therefore, a treatment or consulting team would optimally include or have access to a dermatologist, a surgeon skilled in the management of foot complications in persons with diabetes, a podiatrist, a plastic or vascular surgeon, a wound specialist, a neurologist, a vascular surgeon, an internist or endocrinologist, an infectious disease or clinical microbiology specialist, and a physiatrist. In addition to these specialists, an orthotist or pedorthist is of vital importance for assistance with the provision of pressure-relieving insoles and appropriate footwear, Dr. Embil added.

The patient may need to see a vascular surgeon to evaluate circulation problems, a surgeon for debridement, an orthotist or pedorthist to make an orthotic or brace or to modify footwear, a physiatrist or physical therapist to help with any rehabilitation needed, and a podiatrist for foot care.

“We have adequate evidence on how to diagnose and treat these infections, but it has not yet been widely enough disseminated or properly followed,” Dr. Lipsky said. “Most important is that multidisciplinary diabetic foot teams have consistently been shown to dramatically reduce bad outcomes.”

According to John S. Steinberg, DPM, associate professor in the department of plastic surgery at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, D.C., limb salvage “goes way up when a team is established. Treatments have improved so much that early referral [to the team of specialists] does make a difference in outcome. There is a whole lot more we can do, and it is not automatic that a patient with diabetes and a foot infection will lose a leg.”

Medical options range from no use of antibiotics for clinically uninfected wounds to antibiotic therapy for all infected wounds, along with debridement and/or wound care. An early-stage ulceration can be treated conservatively, according to Dr. Steinberg. This can include debriding the ulcer, which can be done by a primary care physician, foot specialist or surgeon. A topical antimicrobial should be prescribed, although Dr. Embil cautioned against unnecessary use of antimicrobial therapy. The primary care physician or a podiatrist should make recommendations about appropriate footwear that will take pressure off the wound and allow the wound to heal.

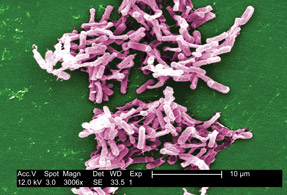

A superficial ulcer with skin infection should also be cleansed and all necrotic tissue and surrounding tissue should be debrided. An empiric oral antibiotic therapy should be prescribed that targets Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci, according to the International Working Group. This can be modified, if necessary, based on the results of properly obtained wound cultures.

According to the IDSA guideline, the initial antibiotic course should be one to two weeks for a mild soft tissue infection and two to three weeks for moderate to severe infection. A severe infection can be treated with broad-spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy, pending culture results, and some wounds may require more than one antibiotic. All wounds should be offloaded to relieve pressure on them.

While outpatient treatment is often adequate for mild and many moderate infections, patients who do not respond to therapy or who have a severe or even moderate infection and complications such as PAD should be hospitalized, according to the IDSA guideline. As inpatients, they may receive intravenous antibiotics, surgical treatment, or specialized diagnostic tests. Dr. Steinberg said patients with deeper wounds and with ischemic changes may need hospitalization to medically stabilize them before their wounds are treated with surgical debridement.

Dr. Lipsky advises considering surgical intervention for patients who present with local gangrene, crepitus, bullae, skin hemorrhage, new anesthesia or severe pain, or systemic symptoms of sepsis. “Failure to respond to apparently appropriate medical care should also suggest evaluation for the need for surgery,” he said.

Some surgical patients may need partial amputation and revascularization. But, with early recognition and treatment, most patients should be able to avoid the need for these drastic interventions. About 80% of newly forming diabetic foot ulcers can be healed within six weeks of standard care, including debridement and offloading on the wound, according to Dr. Steinberg.

“When we talk about limb loss, 84% of the time those proximal catastrophic amputations are preceded by an ulceration,” he said. “If we had just gotten to the patient either at the earliest stage to prevent the ulceration or even if we get to them after they have formed an ulcer, we can usually prevent an amputation.”