Internists play primary role in detecting skin cancer

While it isn't recommended that primary care physicians perform whole-body skin exams for skin cancer, they can and should be alert for skin lesions with malignant features. An easy acronym and other tips and tricks can make the difference.

Primary care physicians are the first line of defense in detecting skin cancer, according to Julia R. Nunley, MD, FACP.

“Accessibility to specialists has become limited due to the sun damage generation and the limited number of dermatologists,” she said, “meaning that more of this burden has fallen on the shoulders of PCPs [primary care physicians].”

It's a burden that has been increasing. Skin cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends tracking melanoma from 1999 to 2008 show that the incidence increased significantly each year among men and women and that mortality rates increased significantly for men.

From 1999 to 2008, the rates of melanoma increased significantly by 2.3% per year among men and by 2.5% per year among women. In addition, the rate of melanoma deaths increased significantly by 0.8% per year among all men, and 1.0% per year among white men. These data are specific to melanoma because central cancer registries do not currently track the incidence of other types of skin cancer such as basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that existing evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against whole-body skin examinations by a primary care physician. However, the task force does suggest that physicians could be “alert for skin lesions with malignant features that are noted while performing physical examinations for other purposes.”

Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Basking Ridge, N.J., took a more specific stance. “We need everyone involved in screening patients for skin cancer so that we can be more effective as a health care providing community to stem the tide of rising epidemic of melanoma and skin cancer,” he said. “I know there are limitations in time and in general, but ideally the PCP should be trained to screen for skin cancer on the back, chest, legs and face.”

Dr. Wang added that quick screens can be incorporated into routine aspects of care. For example, when listening to heart rates, physicians could also look for concerning lesions by asking patients to quickly lift up the fronts and backs of their shirts.

Internists should counsel patients about sun and skin protection, stressed Dr. Nunley, who is a professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Virginia Hospitals in Richmond, Va.

“Part of the role of the PCP is to advise all patients about avoiding peak sun hours between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m., applying high-SPF sunscreen every two hours, using sunglasses and hats, and wearing sun protective clothing,” she said. “They should also make sure patients are getting eye exams, perineal exams and dental checkups because melanomas can form in any of those areas as well.”

Focus on high-risk populations

If screening every patient is not realistic in internists' busy practices, then experts recommend that they focus on screening at-risk populations.

Although skin cancer affects all skin types and people of all ages, certain groups are at higher risk, said Thomas E. Rohrer, MD, a dermatologist and dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Melanoma occurs more often in people who have had intermittent sun exposure, such as office workers or accountants who get sun exposure on vacations, he said.

“For melanoma, people who are at high risk are people who have a family or personal history of melanoma,” Dr. Rohrer said. “People who are light-skinned, have fair hair, blue eyes, or who have had significant sun exposure, particularly in their youth, are all at increased risk.”

People who have multiple moles or a lot of nevi should also get increased attention, he said.

When looking for squamous cell carcinoma, internists should pay attention to patients who have had extensive lifelong sun exposure, such as farmers, Dr. Nunley said. Patients who have undergone an organ transplant and are on immunosuppressive medication are also at increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma, she added.

What to watch for

Multiple tips and tricks can help internists determine if skin lesions are a concern.

“The simplest one is the ugly duckling sign,” Dr. Rohrer said. “If you find one mole that looks very different from other moles on the patient's body, it can be a cause for concern.”

Also, any mole that is changing in size, shape, color or border should be a worrisome sign to the patient or physician, Dr. Rohrer noted. Dermatologists employ the ABCDEs of melanoma to identify suspicious lesions, and Dr. Rohrer encouraged primary care physicians to do the same.

- Asymmetry. If a line were drawn straight through the mole, one half would be unlike the other.

- Border. Be concerned about any mole with an irregularly shaped or jagged border.

- Color. Physicians should be on the lookout for moles with multiple colors within it. Rather than being an even tan or brown color, they may have black, red, purple or a darker spot somewhere in the mole.

- Diameter. Check whether the lesion measures greater than 6 mm, or approximately the size of a pencil eraser.

- Evolution. Any mole or skin lesion that is changing over time is a concern.

With nonmelanoma skin cancer, patients' most common complaint is an area of skin that was sore or was bleeding, seemed to heal, and then began to hurt or bleed again, according to Dr. Nunley. These signs often indicate a basal cell carcinoma. In contrast, squamous cell carcinoma often presents as scaly spots.

“Many things appear as scaly spots on the skin, though, so if squamous cell is suspected it is important for the PCP to palpate the lesion,” Dr. Nunley said. “By palpating the lesion the physician can determine if the lesion is on the skin or if it is infiltrating the skin. Skin infiltration frequently indicates that it could be a squamous cell carcinoma.”

Bring in an expert

When it comes to biopsy and removal of suspected skin cancer, a referral to a specialist, specifically a dermatologist, may be the best decision for the patient. Getting a patient to a specialist is especially important if an internist suspects melanoma. In fact, in this situation, Dr. Nunley even recommended that the PCP call a dermatologist colleague to set up the appointment for the patient before he or she leaves the office.

“Dermatologists who hear about a suspected melanoma from a physician colleague are very likely to squeeze in that patient as soon as possible because they respect their colleague's ability to recognize melanoma,” she said.

Even if a PCP is unsure or unable to confirm a skin cancer diagnosis, a referral to a dermatologist is still recommended. False alarms can be common, but dermatologists would rather see a patient who ends up being healthy than one who lets a problem like melanoma go untreated, Dr. Rohrer said.

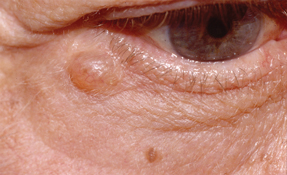

Dr. Wang agreed. “There are many times when a patient is referred by a PCP and there are no concerning lesions, but instead benign lesions called seborrheic keratosis,” he said. “However, there are also many times when a PCP refers to us for evaluation of a basal cell, squamous cell or even melanoma lesion, and they are correct.”