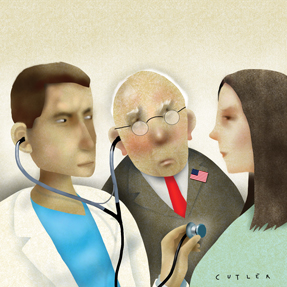

Super fail: Congress sets new low for ineffectiveness

An attempt at political compromise failed, even when the consequences were so sever as to guarantee some type of success. The pressure will only increase in an election year, threatening physician payments, cuts to critical health programs and services, and no end in sight for a solution.

The 112th Congress is setting a new standard of ineffectiveness. Last winter, it got itself into a drawn-out fight over appropriations, which almost led to the federal government shutting down all but “essential” functions. It took an eleventh-hour agreement to cut spending by $300 billion to keep the doors open.

Then, in the summer, it got itself into a protracted battle over authorizing the government to borrow more money. The debt ceiling debate turned into a debacle, putting the federal government on the verge of having to default on its obligations. As a price of staving off default, Congress and the Obama administration agreed to legislation to carve another $900 billion out of “discretionary” spending over the next decade.

The agreement also created a “super-committee” of members of Congress, evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, House and Senate, to recommend an additional $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction, including, potentially, cuts in entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, along with tax increases. The super-committee was required to release its plan by Thanksgiving; Congress would then have until Christmas to vote it up or down, with no amendments or filibusters allowed.

To create a strong incentive for Congress to reach a consensus on spending cuts and revenue increases, the debt ceiling legislation put in place an automatic enforcement mechanism called sequestration. If the super-committee process failed, sequestration would impose the required $1.2 trillion in savings through automatic cuts, 50% from defense spending and 50% from domestic programs, with Medicaid, Social Security, Medicare benefits, and some other programs for low-income persons and veterans exempted. The thinking was that the across-the-board cuts would be so unpalatable that the super-committee would have no choice but to reach a bipartisan accord.

Well, we now know how that one turned out. The super-committee—surprise, surprise!—deadlocked over ideological and partisan issues and couldn't produce a plan. With no super-committee agreement, sequestration will now be imposed by automatic pilot. In January, the administration was scheduled to release a report on how the sequestration cuts will affect spending by each federal agency and program.

About $600 billion of the cuts will come from defense, and $600 billion from the non-exempt domestic programs. But since defense spending is only 20% of total federal spending, the defense budget takes a disproportionately bigger share of the total savings. On the domestic side, non-entitlement spending will bear a disproportionate share of the reductions because Medicaid and Social Security are exempted and the Medicare cuts are limited to a 2% reduction in payments to “providers.”

Here's the rub: Sequestration cuts don't actually go into effect until January 2013, giving Congress 12 months to try to reverse them or come up with an alternative plan. But reversing sequestration is easier said than done, because Congress would then have to find equivalent savings and/or tax increases, or risk another downgrade of U.S. bonds if it backs out of its commitment to lower the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion. Plus, President Obama has said he will veto any bill to reverse sequestration, unless it is replaced with a “balanced” plan of revenue increases and cuts that will save the same amount.

In other words, we are looking at another protracted battle this year between Republicans and Democrats, and the White House and Congress, on how best to cut the budget deficit and prevent sequestration. This time, it will all be taking place in the spotlight of presidential and congressional election year campaigning, which will drive the discussions to sharpening the differences between the candidates and parties, not toward achieving bipartisan consensus.

So where does all of this leave funding for programs of interest to internists?

In the short term, physicians were stymied in their efforts to get Congress to repeal the Medicare sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula, which causes annual scheduled cuts in payment to doctors, as part of a big deficit reduction agreement that would include sufficient budgetary offsets to pay for SGR repeal. (Getting rid of the SGR has an estimated cost of $300 billion.) But if the super-committee had reached an agreement, other programs, like Medicare funding for graduate medical education, might have been subjected to much deeper cuts than required by sequestration.

Looking to next year, though, sequestration will require an average reduction of more than 7% in funding for programs that are critical to public health and safety, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration, and in grant programs to help train more physicians. Also, sequestration will cause a 2% reduction in Medicare payments to hospitals (including teaching hospitals) and physicians. In the case of physicians, this will be in addition to any scheduled cuts from the SGR.

The 112th Congress's ineffectiveness only postpones the inevitable. At some point, a future Congress will need to reach a bipartisan plan to cut the deficit by many, many trillions more than the $1.2 trillion being considered by the super-committee. Because health care spending is the greatest single driver of public debt, Congress will then have to find a way to dramatically reduce health care costs. The longer it waits, the greater the cost of inaction, and the deeper the eventual cuts.