Sports internists treat players as patients

These internists turned their own athletic pursuits into careers for professional sports teams, treating high-caliber athletes as they practice and play. When working the sidelines, it's just another day not at the office.

Working for a professional sports team can be similar to a traditional office-based practice. Internists who hold these jobs handle chronic conditions and acute injuries, convey difficult medical concepts to their patients, coordinate care among subspecialists, and sometimes deliver bad news.

But when they're working the sidelines of a game or a match, every decision puts millions of dollars in revenue, contracts and endorsements on the line. Tens of thousands of screaming fans offer their clinical opinions, or even worse, their non-clinical ones, while the internist is trying to assess the patient.

And don't forget the athletes themselves, highly trained, physically exceptional and extremely competitive people who are driven to get back on the field, even if it's not always in their best interests.

Unusual career arc

Sports medicine isn't the typical internal medicine career. Most sports medicine fellowships go to family physicians, and sometimes internists aren't even considered for them, said Selina Shah, MD, an ACP Fellow who practices at the Center for Sports Medicine in San Francisco and Walnut Creek, Calif. She chairs an internal medicine interest group that addresses this and other issues within the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. The society has just over 2,000 members, three-quarters trained in family practice and fewer than one in 10 trained in internal medicine. Another group, the American College of Sports Medicine, reports that about 2% of its members identified themselves as internal medicine specialists.

Family medicine does a little of everything, Dr. Shah said, and already has a focus on musculoskeletal medicine, as well as on athletes of all ages. Also, the society's founding members 20 years ago were all trained in family practice. When internists choose sports medicine, it's usually because they're jocks, she said.

Dr. Shah's sport is dance, which she has done recreationally and professionally since she was three years old. Following her internal medicine residency at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., a sports medicine fellowship at Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Los Angeles, led her to a career treating not only pro athletes but Olympic figure skaters, weight lifters and gymnasts. She continued her involvement in dance by volunteering her medical services for professional dance companies across the San Francisco Bay area.

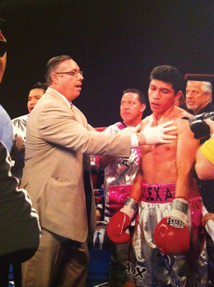

Internist Marc Shaber, MD, has always focused on boxing. Since the age of five, he's followed the sport, and he also boxed in high school. He's now a ringside medical monitor for the State Athletic Control Board in New Jersey.

Dr. Shaber is an internist employed full-time in a private practice setting in which the other physicians are family practitioners. He also has a year of general surgical training. His knowledge of lacerations helps him when examining injured fighters between rounds. But he relies on his boxing experience to help him determine whether and when to stop a fight.

“You have to be knowledgeable about the sport itself,” he said. “You have to understand what's happening in the context, what's happening between the rounds, what to look for during a fight. If you don't understand the sport, you're not going to be a good ringside physician.”

Deep lacerations that are bleeding into the eye and large hematomas that impair vision are obvious signs. If a fighter can't see, he can't defend himself. Dr. Shaber also has to consider how well a fighter is defending himself, or whether he's fighting back at all, as well as how the fighter responds between rounds.

“It's a lot of pressure,” Dr. Shaber said. The fans want to see hard hits, bouts are often televised, and championship fights bring a new level of intensity. He may have to assess a fighter who doesn't speak English, as well as work around trainers and the “cut man” working on the fighter's injuries between rounds.

“You're trying to protect the fighter and they're interested that their fighter continues,” Dr. Shaber said. “You have to aggressively, assertively get in the ring, and they try to block you, but you ask the referee or the inspector to get you in there.”

His question to the fighter is simple: “Do you want to continue?” A lot of times, they don't.

“That makes your job easier,” Dr. Shaber said. “If they're taking a lot of punishment, they're not trying to defend themselves, they're not trying to fight back, they seem a little wobbly, you get to the point where they're not responding appropriately, then you've got to stop the fight. It's a little hard sometimes when it's late in the fight, and you have a 12-round fight, and it's the 11th round. You want to let it go. The fans might not be happy. But if someone's taking a lot of punishment, we will try to protect the fighter to fight another day.”

Internal medicine's role

In addition to the extremes and excitement of sideline duties, internists who work for pro sports teams manage the day-to-day well-being of their players just as they would for office-based patients.

Athletes play with a surprising range of chronic conditions, including type 1 diabetes, osteoporosis and sickle cell trait. Infectious diseases can range from sexually transmitted diseases to those stemming from dormitory settings, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Internists also manage the everyday ailments that can affect just about anyone.

Anthony Yates, MD, an ACP Fellow who has been the team internist for football's Pittsburgh Steelers for more than 30 years, added, “We practice medicine. It's still the same approach, the same considerations for the same signs and symptoms. The players are still made of the same flesh, although they may be a bit bigger.”

Kathy Weber, MD, an ACP Member, said her background in internal medicine and sports medicine is the perfect blend of training. She's a former college athlete who works at a private orthopedic practice associated with Chicago's Rush University Medical Center, which provides care for Chicago's pro basketball and baseball teams, the Bulls and the White Sox. She is Major League Baseball's only female team physician and was the National Basketball Association's first female physician.

“When someone breaks a bone, we have an orthopedist that can fix it,” she said. “But I also have the expertise to evaluate the injury and decide if it does or doesn't need to be fixed.”

Internists are in a position to detect medical zebras, too. Dr. Shah recounted a case of one athlete with pain and tenderness in her rotator cuff. She ordered an MRI and a creatine phosphokinase test, which showed levels of more than 10,000 U/L. The MRI showed a swollen rotator cuff but no tears. “It was very clear that it was rhabdomyolysis. Later her [thyroid-stimulating hormone level] came back consistent with hypothyroidism. That's where internal medicine and sports medicine really can merge.”

Dr. Weber added, “Part of taking care of the professional athletes requires determination of return to play after the athlete has an injury. In some cases the use of an MRI early in the evaluation can help determine the degree of injury and the likely timeframe for the athlete to be back on the court or field.”

Coordinating communication

Contracts, championships and even careers can hang in the balance when a pro athlete is injured. Delivering tough news is important and requires coordinating communication among the doctors, the trainers, the coaching staff and all the other people who surround an athlete, such as agents and family, said Paul J. Gubanich, MD, an ACP Member. The goal is to avoid any confusion by the player about what to do about an injury.

“Those scenarios are best handled by being very transparent, frank and upfront with athletes,” Dr. Gubanich said. “Everything we do in medicine and everything we do in life is a risk-benefit assessment.”

Dr. Gubanich was an athlete growing up, so after completing his internal medicine residency at the Cleveland Clinic, he pursued a sports medicine fellowship there. Through that facility, from 2004 to January of this year, he treated pro athletes from Cleveland's three major sports teams, the Browns, Indians and Cavaliers; a women's pro football team, the Fusion; and a minor league hockey team, the Cleveland Barons. He has since moved back to OSU Sports Medicine to pursue public health initiatives that let him apply his experience with professional athletes to the community, and to encourage exercise in children from fourth through sixth grades.

Dr. Gubanich said his goal when working with professional athletes, and sometimes with their families, agents and coaching staff, was to assess risk and guide the player to recovery. He was required to weigh whether an injury is painful but can be played through, or to decide that playing with an injury is career- or even life-threatening.

To a certain extent, Dr. Shah and other internists said, their patient population is easier to communicate with than the general primary care patient. Dr. Shah said her professional athletes tend to be fit, active, lean and motivated, “and they for the most part adhere to the advice that you give them. They comply and they tend to get better because of it.”

Many internists who go into sports medicine rely on their own athletic backgrounds to help them adapt medical practice to their professional sports environment and understand their patients' needs.

“Being an athlete myself, with staying in shape a priority, makes it easier for them to relate to me,” Dr. Shah said. “I really mean what I say. ... If I'd been out of shape and inactive and requested that patients comply with my advice, I don't know that the patients would really take me as seriously.”

The other ‘Big C’

Concussions have become the “Big C” in every sport, at every level. Pro sports leagues have adopted increasingly tougher rules to clear players to return after taking a hit, and college and high school associations are realizing the “pernicious” nature of concussion in younger athletes, according to Dr. Yates.

“Sometimes a concussion is hard to nail down. Do you feel dizzy? Do you feel fatigued? Do you have a headache? You can't take a picture of that, or run a blood test,” he said.

Internists with sports medicine training who work for pro teams may have an edge in diagnosing concussions because they see players frequently throughout the season and get to know them well. Developing rapport and trust with the players is important, Dr. Weber said, especially when a decision needs to be made to remove the player from a game following an injury or a concussion.

“During the concussion evaluation, even if the player answers the questions correctly I may notice that they are not at full mental function, so I may make the decision to remove them from the game,” Dr. Weber said. “The rapport I have developed with the players lets them know that I am making a medical decision that is in their best interest and I will work with them to allow a safe return to play as soon as possible.”

Once, she examined a player in the locker room who insisted he was fine, but she knew something was wrong and held him from the game for further observation. By the end of the game, his concussion symptoms had become much more apparent.

“One of the orthopedic fellows came up to me after the game and said ‘Kathy, that was a great call,’” she said. The fellow admitted that based on the player's answers, he would have likely let the player return to the game, especially with the player insisting that he was fine and pressing to return.

Internists' sideline tasks are not always so subtle. Dr. Yates recalled when Steelers quarterback Tommy Maddox was injured on a play in November 2002.

“My career flashed before my eyes when I realized that a rare, catastrophic neck injury had probably just happened,” Dr. Yates said.

Mr. Maddox lost consciousness on the field after what was eventually diagnosed as an impact injury to his spinal cord. The spinal cord concussion left Mr. Maddox temporarily paralyzed from the neck down.

“Internists as a whole don't deal with that sort of injury, although we train regularly for such an event,” Dr. Yates said. “I deal with concussions of head. But I was the guy responsible for airway management, because I have pulmonary training. It's a scary moment when it's a guy you know very well, and you have visions of a broken neck, confining him to life in a wheelchair.”

Eighty thousand fans were quiet as Dr. Yates instructed the medical staff, and an ambulance crew drove onto the field to transport Mr. Maddox to the hospital. The quarterback recovered full motion and returned to the field two weeks later.

A juggling act

Careers in sports medicine feature occasional emergencies, but more commonly they involve long hours covering practices and games while juggling a full-time career in the office. The physicians all have regular office hours with private practices, and have to balance these full-time careers with pro sports seasons. Dr. Shaber travels the state of New Jersey year-round on weekends to cover matches. Other physicians must plan to cover training camps and games according to their teams' schedules.

Particularly for baseball, which has games nearly every night, the chief physicians rely on larger groups of doctors within their practices or medical centers to make sure every game gets covered by enough physicians.

During the regular season, the home team's physicians cover visiting teams' players. But, during championships, internists travel with their own teams to the away games.

Dr. Weber explained, “During playoffs, [teams] want their own doctor to be making decisions. We know the players better, and if you're on the fence and you don't know the opposing player that well, you might say they shouldn't play. But if they're your players, you know if they're able or not to play.”

When the White Sox went to the World Series in 2005, Dr. Weber accompanied the team throughout the playoffs, sometimes returning home at 3 a.m. and sleeping in her office in her suit to see her regular patients at 8 a.m.

The busy schedules and stressful work do offer some perks, like the best seats in the house, and some impressive jewelry. Dr. Yates has earned four Super Bowl rings during his tenure with the Steelers, “enough for my wife and my three daughters,” he said.

And when the White Sox swept the World Series in four straight games, Dr. Weber also received a championship ring.

“I love my ring,” she said. “I'm hoping for an NBA ring to add to my collection.”