Attribution error confounds a diagnosis after colon cancer

A rapid deterioration in mental status confounds a gastroenterologist following a patient for colon cancer. Following a hospital admission, the internal medicine resident reviews the patient's history for the clue to the right diagnosis.

Zahia Esber, ACP Associate Member, who practices at McKenzie-Willamette Medical Center in Eugene, Ore., told us about a case of a 71-year-old obese woman whose mental status deteriorated rapidly while in the hospital.

The patient had undergone a sigmoid resection in December 2009 for colon cancer. At that time, her mental status was intact. Three weeks after surgery, she returned to the hospital because of nausea and anorexia. She told the admitting physician that her symptoms began about two weeks after surgery.

A gastroenterologist consulted on the case. Detailed evaluation did not yield a clear diagnosis. He thought that the patient might be depressed from her diagnosis of colon cancer. She was discharged on an anti-emetic and an antidepressant medication.

Symptoms persist

The patient was readmitted several weeks later for persistent symptoms of nausea and anorexia. While in the hospital she was noted to have an abrupt decline in mental status. She developed dysarthria and after several days barely spoke at all. A neurological consult was obtained. In addition to the impaired mental status, the neurologist noted a symmetrical peripheral neuropathy and tenderness to palpation of the lower extremities. There were no focal motor deficits.

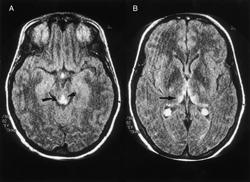

Initially the presumptive diagnosis was stroke or brain metastases. However, imaging, including CT scan and MRI/A, were unrevealing. EEG showed no seizure activity. Lumbar puncture was performed, and no abnormalities were noted in the cerebral spinal fluid. Because of the history of colon cancer, a screen for antibodies related to paraneoplastic syndrome was obtained with negative results.

Dr. Esber took over the care of this patient one week after admission. She was concerned that the patient's neurologic symptoms had developed while in the hospital. Her first thought was that one of the prescribed medications might have caused the decline in mental status. However, once all possibly causal medications were withheld, the patient's condition continued to deteriorate. Dr. Esber went back over the medical record in detail, but found no clues.

Checking the history

“I tried to make sure that nothing had been missed,” she told us. The record was unclear about the patient's condition at home, so Dr. Esber contacted and interviewed several family members. “Too often, we are so busy that we have no time, and we rely only on the history from the chart.” She learned from the patient's son that the patient had hardly been eating for months and had lost a substantial amount of weight, although she was still obese.

“I stayed late after my shift and met up with the neurologist, who graciously sat down with me to go over the case after all of the workup,” Dr. Esber said. The neurologist and Dr. Esber returned to the differential diagnosis of metabolic encephalopathy. Dr. Esber was struck by the history of poor food intake reported by the patient's family. She wondered whether a nutritional deficiency had been prematurely discounted in evaluating a woman who was so overweight.

If the patient was thiamine deficient, then the decline in mental status might have been precipitated by glucose in the patient's intravenous fluids. The patient, whose condition was progressively deteriorating, was empirically treated with parenteral thiamine. Within days, she became alert and her dysarthria improved. “Her son, who came to visit from California, was the first to hear her speaking clearly,” Dr. Esber said. Her leg pain improved. The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing facility with instructions to provide thiamine replacement until she could resume an adequate diet.

This case was not classic for thiamine deficiency. We usually consider the diagnosis in an alcoholic patient. It has also been described in patients with anorexia nervosa, cancer and AIDS. In most cases there is obvious malnutrition. Typical findings of Wernicke's encephalopathy include the triad of mental status changes, oculomotor dysfunction and gait ataxia. This woman was not an alcoholic or obviously malnourished and had no eye findings on exam.

Attribution error

The assumption that an obese woman would not be nutritionally deficient is a form of attribution error. The stereotype in our mind of an overweight person is one who eats to excess, and therefore we may fail to attribute symptoms to the lack of an essential nutrient. The possibility of a vitamin deficiency was reconsidered after obtaining a detailed dietary history from the patient's family. After obtaining this information, Dr. Esber and the neurologist systematically reviewed the long list of etiologies for metabolic encephalopathy, winnowing the differential diagnosis by linking it to the peripheral neuropathy and thereby arriving at the diagnosis of thiamine deficiency.

Thiamine deficiency is not reliably diagnosed by laboratory tests, although these can be helpful. The recommendation is to empirically treat any patient suspected of thiamine deficiency, as was done in this case. Improvement in symptoms and signs can occur rapidly and dramatically after administration of the vitamin, as seen in this patient.

During her training at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Dr. Esber cared for many patients with poor nutrition and chronic alcoholism, but she had never seen a case before of thiamine deficiency. “I had to keep digging for the diagnosis,” Dr. Esber told us. “Here, the history was very important.” Her careful attention to the medical history helped her avoid making an attribution error related to the patient's obesity, and allowed Dr. Esber to arrive at the correct diagnosis and provide essential treatment.