What to do when one expects everything to fit, but it doesn't

James Hennessey, FACP, reports on a young woman's elevated testosterone level, and how he made a diagnosis even though the lab results and imaging conflicted. Our diagnostic experts consider confirmation bias and how this internist sidestepped being misled.

At a recent weekly case conference at our hospital, we heard about a young woman with an elevated testosterone level. The patient was evaluated by James Hennessey, FACP, prior ACP governor from Rhode Island and currently director of clinical endocrinology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, along with an endocrine fellow, Laura Sweeney, MD.

Case study: Polycystic ovarian syndrome suspected

The patient was a 19-year-old art student at a local university. She was seen by a nurse practitioner at the student health services after a prolonged menstrual period lasting more than 10 days. Prior to this, her menses were regular and had lasted no more than five days. She also complained of increased facial hair.

The nurse practitioner sent her for a pelvic ultrasound and this reportedly showed normal ovaries, although it was noted that the right ovary, measuring 4.4 cm, was larger than the left, which measured 2.7 cm.

Blood tests showed both an elevated total testosterone level of 253 ng/dL (more than five times the upper limit of normal) and a free testosterone level of 51.5 pg/dL (more than seven times the upper limit of normal). Additional tests showed normal levels of prolactin (11.6 ng/mL) and DHEA sulfate (274 µg/dL). A 17-OH progesterone level was quite elevated at 519 ng/dL (reference range, 15 to 70 ng/dL).

The nurse practitioner told the patient that she had a “hormone imbalance, likely polycystic ovarian syndrome.” The patient was started on an oral contraceptive pill and referred for gynecologic and endocrine evaluation.

Consultation raises further questions

Dr. Hennessey saw the patient one month later. She was in good health, and she was taking no medications other than the oral contraceptive pill she had started a few weeks earlier. She denied the use of any supplements and did not smoke, drink or use illicit substances. She told Dr. Hennessey that she felt well.

On review of systems, the patient admitted that she had gained some weight since starting college in the fall, and she attributed this to eating cafeteria food. She had also noted some facial hair above her upper lip and on her lower abdomen that had not been present previously, but she was not particularly bothered by this. She had noted no changes in her mood or libido.

On physical examination, she was five feet tall and weighed 134 pounds for a BMI of 25.5 kg/m2. She did not have a deep voice and showed no signs of virilization. Her examination was otherwise unremarkable except for mild facial hirsutism and increased terminal hair on the lower abdomen and inner thighs. There was no terminal hair on the chest or on the back. The gynecologist who had examined the patient reported that the clitoris may have been slightly enlarged but the exam was otherwise normal and there were no adnexal masses.

Dr. Hennessey ordered some additional laboratory tests. The testosterone level was further increased, now measuring 360 ng/dL (reference range, 6 to 82 ng/dL); the free testosterone level was also significantly elevated, measuring 10.1 pg/dL (reference range, 0.0 to 2.6 pg/dL). The DHEA sulfate level was again normal, measuring 274 µg/dL (reference range, 148 to 407 µg/dL). The 17-OH progesterone level was again elevated at 466 ng/dL.

High testosterone level cause for concern

Dr. Hennessey told us that the very high testosterone level made him quite concerned that the patient had either an adrenal tumor or an ovarian tumor. He immediately sent the patient for an abdominal and pelvic CT scan. This was read as showing normal adrenal glands and normal ovaries.

“I was not particularly reassured,” Dr. Hennessey told us, but given both a normal pelvic ultrasound and a normal pelvic and abdominal CT scan, he felt he should consider other more rare diagnoses such as a form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. After consultation with a colleague specializing in reproductive endocrinology, he performed a cosyntropin stimulation test.

Cortisol increased appropriately from a basal value of 10.8 µg/dL to a peak value of 34 µg/dL after cosyntropin, but there was no change in the testosterone or 17-OH progesterone level. Further, after treatment with dexamethasone, 0.5 mg four times per day for two days, neither the testosterone nor the 17-OH progesterone suppressed at all.

Digging deeper

At this point, Dr. Hennessey became convinced that there must be an ovarian tumor despite the negative imaging. He contacted an expert ultrasonographer at our hospital and charged him to “find this young woman's ovarian tumor; it just has to be there.”

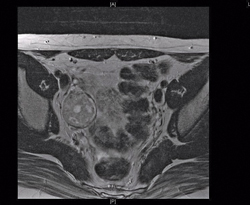

Sure enough, the ultrasonographer found it. Although a transvaginal ultrasound was not tolerated, a right ovarian mass was seen on transabdominal ultrasound. This was confirmed on MRI scan, which showed a normal left ovary but a right ovarian mass measuring 3.2 × 3.2 × 3.9 cm.

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy and removal of the right ovary. Pathology confirmed the presence of a Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, intermediate to poorly differentiated, measuring 5.7 cm. A subsequent fertility-sparing staging procedure was negative for additional sites of malignancy.

The patient did receive chemotherapy (bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin). Following this treatment, her total testosterone level fell to 19 ng/dL, and her 17-OH progesterone level decreased to less than 8 ng/dL.

Atypical cases and “prototype bias”

Here, we have a physician confronted with test results that clash. The repeated hormonal measurements of total testosterone, free testosterone, and 17-OH progesterone indicated the presence of a virilizing tumor in this young woman, but there was no evidence of tumor on radiological assessment, first by ultrasound and then CT. This is a setting ripe for “confirmation bias,” that is, discounting contradictory data. In this case, that would mean discounting either the laboratory tests or the imaging.

As physicians, we think by “pattern recognition,” assembling key elements from the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiological imaging to arrive at a diagnosis. Sometimes it is appropriate to discount certain data that do not fit; other times it is not. Pattern recognition works best for a typical case.

Atypical cases are challenging cognitively and can lead to so-called “prototype bias,” where we ignore the reality that clinical presentation often varies widely. This young woman was an atypical case. Her lack of virilization and normal imaging did not fit into the typical picture of a testosterone-producing tumor that was indicated by the elevated hormonal levels.

Dr. Hennessey appropriately “took a detour,” as he told us, to rule out the rare possibility of congenital adrenal hyperplasia with cosyntropin stimulation testing and dexamethasone suppression testing. He then returned to the problem of “What do you do when you expect everything to fit, and it does not?”

Careful review essential

Dr. Hennessey reviewed all of the data again. He knew that this was not a simple laboratory error because the elevated testosterone measurements were repeated and the free and total levels were internally consistent. So, he closely followed the patient with serial testing and imaging, hypothesizing that her disorder would ultimately reveal itself, as it did.

It is likely that this young woman was seen early in the course of her disease, referred because of the misdiagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome. The elevated testosterone levels had not yet caused typical virilization and the tumor had not yet developed to sufficiently alter normal ovarian anatomy, so the radiologist could only note increased size of one ovary but no features of cancer.

In this era of cost containment, we are mindful of expensive repeated testing, especially imaging studies, but sometimes multiple assessments are needed in the face of a disease in evolution. Dr. Hennessey kept an open mind, free of confirmation or prototype bias, and continued to observe, think and evaluate the patient until the correct diagnosis was made.