Uncertain diagnosis for pain leads doctor to dig further

A 66-year-old woman presents with abdominal pain radiating to her back, and CT scans show multiple lesions worrisome for metastatic disease. But when the pain resolves and the lesions don't change, one internist reconsiders the diagnosis.

Carlos I. Smith, ACP Member, from the Medical Center at Ocean Reef, Key Largo, Fla., submitted a case of abdominal pain. The patient was a 66-year-old woman who had been seen only once a year for checkups. She had a history of impaired glucose tolerance and borderline hypertension in the setting of central obesity, but was taking no medications. The patient reported she had never smoked cigarettes and drank two glasses of wine twice a week. She described the pain as periumbilical with radiation to the back. It had been present constantly for several weeks, waxing and waning in intensity. There was no precipitant and there were no other associated symptoms.

“We spent quite a bit of time talking about her abdominal discomfort,” Dr. Smith recalled. “There was no clear diagnosis after a detailed history and complete review of systems. I wasn't sure what it was.” On physical examination, the patient had mild discomfort on palpation of the periumbilical region without a definite mass. “She was very concerned about the pain,” Dr. Smith said.

The new onset of periumbilical discomfort, the radiation of pain to the back, and the persistence of pain over several weeks prompted Dr. Smith to order laboratory tests, including liver function tests, amylase and lipase. Her blood tests were all normal.

Dr. Smith started as a hospitalist but has practiced general internal medicine for the past three years. One of the most difficult challenges in practicing internal medicine is to avoid missing a serious diagnosis. Of course, most patients who present with vague abdominal discomfort will not have a significant illness. The challenge is to decide when to order expensive and/or invasive testing. Several features of this case were of concern, including radiation of the pain to the back, persistence over several weeks, the patient's own concern and the lack of an obvious explanation for the symptom. In cases like this, a physician must exercise clinical judgment.

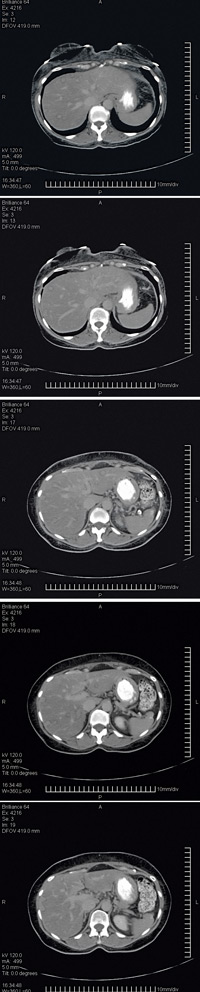

Dr. Smith ordered a CT scan of the liver that showed an unexpected finding: many target lesions, about 1 cm, consistent with metastatic cancer. He reviewed the films with the radiologist who had read the scan and confirmed that this was most consistent with metastatic cancer. Dr. Smith proceeded with a more extensive evaluation looking for a primary malignancy. Mammography, colonoscopy and chest X-ray were all negative. Tumor markers, including CEA, CA125 and alpha-fetoprotein, were also all within normal limits.

Dr. Smith then sent the patient for a CT-guided liver biopsy. The pathologist read the results as steatosis. Dr. Smith told us, “I thought for sure the radiologist had missed it.” He spoke directly with the radiologist, who felt confident that he had been within the lesion but agreed to do a second biopsy. A second biopsy was performed, and again the pathology report was steatosis. Dr. Smith reviewed the biopsy slides with the pathologist but there was no indication of malignancy. Despite the apparent certainty on imaging, Dr. Smith began to rethink the diagnosis.

In past columns, we have discussed confirmation bias. This is the tendency to remain fixed on an initial diagnosis and discount subsequent contrary data. Dr. Smith avoided confirmation bias. “At this point, I started to doubt the diagnosis of cancer,” he said, “but what was it?”

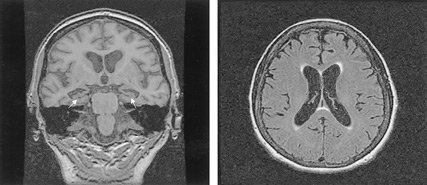

Over the ensuing weeks, the patient reported that her abdominal discomfort had resolved and she felt entirely well. Yet there was no diagnosis to account for the findings on CT scan, and this uncertainty was distressing to both the patient and Dr. Smith. The patient planned to visit her daughter in New York City and requested a second opinion while there, which Dr. Smith encouraged. The patient went to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, where an MRI scan confirmed the lesions in the liver. The pathology was reviewed and no malignancy was seen. The diagnosis remained unclear. Yet a diagnosis of cancer could not be completely excluded.

The recommended course of action was serial imaging. A follow-up MRI scan at Memorial Sloan-Kettering six months after the onset of symptoms showed no change in the multiple target lesions. The patient continued to feel well.

“At this point, I became convinced that it was not cancer,” Dr. Smith said. The patient remained concerned that she had no diagnosis and was referred to a university hospital in Florida where a gastroenterologist told her that, despite her statement that she only drank modestly, she had alcoholic liver disease; he suggested a referral to Alcoholics Anonymous. “The patient was not happy with the encounter,” Dr. Smith said.

“Initially, cancer was my overriding concern,” Dr. Smith said, “but the diagnosis is still uncertain. At this point, my assumption is that this is an atypical radiological presentation of hepatic steatosis. I apologized to her about the incorrect diagnosis. It initially seemed almost certain that this was metastatic cancer, but my working diagnosis was wrong,” Dr. Smith said. The patient replied that no apology was needed.

Why did Dr. Smith apologize? A physician apology to a patient has become a central tenet of risk management, an important component of how to deal with a medical error that has harmed a patient. Here, there was no error.

Dr. Smith reflected on each step he took in this case. “Should I have waited to order the CT scan?” Dr. Smith asked himself. Yet in the end, he probably would not have done things differently. Dr. Smith had communicated his clinical thinking to the patient throughout the process, explaining the rationale for each blood test and scan, as well as the liver biopsies and referrals to other specialists. There were no physical damages related to the incorrect diagnosis and no concern about a lawsuit.

But Dr. Smith recognized the emotional fallout of telling a person that she likely had metastatic cancer. By apologizing, he demonstrated genuine empathy, putting himself in the patient's place as she spent months pondering that she might soon die. In this setting, an apology strengthens the bond between doctor and patient. Part of Mindful Medicine is to be aware of the emotional consequences of your thinking.