MS confounds, calls for better coordination

Internists are closely involved in care for multiple sclerosis, from recognizing symptoms to preventing complications. As the first line of defense, primary care physicians can find reassurance in guidance from a recent consensus paper on differential diagnosis.

It affects approximately 2.1 million people, with no cure and no unique diagnostic criteria. “Sometimes we're never really 100% sure,” said one expert.

No wonder, then, that multiple sclerosis (MS) poses challenges for internists. Although diagnosis falls under the expertise of neurologists, general internists are often closely involved in MS care, from recognizing the first symptoms to treating or preventing complications.

“A lot of times patients will complain of whatever symptoms they're having and call up their internist as their first line of defense. They end up either making the referral or reassuring the patient that they don't have anything going on,” said Clyde E. Markowitz, MD, director of the MS Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Physicians struggling with the decision between referral and reassurance can take guidance from a recent consensus paper on differential diagnosis, published in Multiple Sclerosis in November 2008. In recent interviews, experts in the field also offered additional advice on how internists can provide the best care for their patients with MS.

The consensus paper delves deep into the details of distinguishing MS from other conditions. “Our goal was to walk the person through what would be the considerations for making the diagnosis,” said co-author Steven L. Galetta, MD, chief of neuro-ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania.

The experts' role

In one indication of the complexity of that task, the consensus paper included three pages of red flags, symptoms that suggest a diagnosis other than MS. However, general internists aren't expected to sort through that level of detail. In fact, the experts specifically asked that non-specialists not diagnose the disease.

“The internist sometimes goes ahead and tells the patient that they have MS. It's really frightening for the patient to hear that, so it might be better for internists to be a little vague about it: ‘I'm not really sure what your numbness is from, but you should see a neurologist,’” said Barbara Scherokman, FACP, a neurologist in Fairfax, Va.

But don't err in the other direction, either. “The most common reason not to make a diagnosis of MS is because the symptom gets better,” said Richard A. Rudick, MD, director of the Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. “If the person has mild blurring of vision which then gets better, the primary care doctor may not pursue the diagnosis. They may just ignore it.”

Symptoms are often mistaken for a number of other conditions, thus the long list of red flags. “People will complain of some tingling in their hands or their feet or numbness. It's usually felt to be related to an injury or a compression, sleeping on something funny. Those are the kind of things you see in day-to-day clinical practice and it's sometimes difficult to figure out if it's routine spine stuff or the first onset of symptoms related to MS,” said Dr. Markowitz.

The consensus paper offers some criteria to differentiate disorders that resemble MS.

Neuromyelitis optica, also known as Devic's disease, causes vision loss and spinal cord dysfunction, but not the cognitive problems associated with MS. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) also has similar effects to MS, but it's not progressive. “We tried to set criteria to distinguish ADEM from MS, by putting a time limit on how long new symptoms could appear. Beyond three months, it's MS,” Dr. Galetta said.

It's necessary to differentiate these similar conditions from each other because each requires different treatment.

So how to differentiate these diseases, and the many others that can mimic MS, from the real thing? Patient demographics are one clue. “If somebody's 70 and they're complaining of lower back pain radiating down their leg, MS is not the first thing you're going to think of. But if you have a 35-year-old woman who had numbness in her feet, you have to be more concerned,” Dr. Markowitz said.

But don't rely too heavily on demographics, cautioned Anne Cross, MD, a neurologist from Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. “People think of it as a disease of young Caucasian females because that's what people learned in medical school. But in fact, there are quite a few African-American males with MS.” Patients who don't fit the usual profile or have subtle or unusual symptoms are the most likely to elude diagnosis, Dr. Cross noted.

Experts acknowledge that they're setting up a difficult standard: Don't diagnose the disease, but don't send patients home who could have it; use demographics to pick out likely cases, but don't miss the unusual ones. The complexity is in the nature of the disease.

“One of the problems we face is that each of the things that can be seen in MS that is abnormal can be seen in other diseases as well. There is nothing that we see in MS that is pathognomonic,” said John Richert, MD, a consensus paper co-author and executive vice-president for research and clinical programs at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

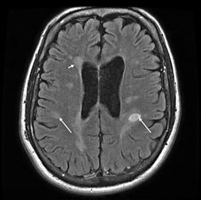

Even the most effective diagnostic tool, the MRI, can be misleading. “Sometimes the diagnosis gets made because of some white spots on the MRI scan in a person who doesn't have MS,” said Dr. Rudick. “It's not uncommon to see somebody who has fatigue or tingling and who has nonspecific spots on the MRI scan who has been told they have MS and they probably don't.” Migraines, for example, can also be associated with abnormal MRI spots.

The MRI is still a requirement for diagnosis and a good place for internists to start, the experts said. “It would certainly be best if they would refer the patient to a neurologist after having obtained a basic screening bloodwork panel and MRI scan,” said Maria K. Houtchens, MD, a neurologist at the Partners MS Center in Boston.

Then the case should be passed along or at least shared with someone who has extensive knowledge of the disease. “The MRI has to be interpreted by somebody who's an expert,” said Dr. Galetta.

In addition to their expertise, neurologists bring other advantages to the diagnostic process. “The neurologic history and exam can take 30 to 45 minutes and frequently internists don't really have time,” said Dr. Scherokman. “Fortunately, we have a lot more time than they do. In my group, internists have 5 or 10 minutes to see a patient and neurologists have 45 minutes to see a new patient.”

Reason for hurry

The diagnostic process may be slow, but then it's important for treatment to move quickly. “Early therapy is better than late therapy. In all the pivotal clinical trials of MS medications, those patients that get on drugs in the delayed treatment arm do not fare as well as those who were on the drug right from the start. They never catch up,” said Dr. Galetta.

General internists have an important role in making sure their patients get treated early and consistently. “The disease needs to be managed proactively in order to prevent the later stages of MS from developing and causing complications like neurologic disability,” said Dr. Rudick. “The internists need to understand that concept so they can urge their patients to remain compliant with their medication [and] their follow-up visits to keep the disease under control.”

Therapy for MS is analogous to treatment for high blood pressure, Dr. Rudick said. “The reason that the internist treats hypertension is not that hypertension is causing problems right then and there for the patient.”

Internists also need to be aware of the relationship between MS exacerbations and other medical problems. Anything from a urinary tract infection to pneumonia to surgery can intensify symptoms, said Dr. Scherokman. “We frequently ask internists to help us out with diagnosing and treating underlying medical problems that can bring on an attack of MS.”

Cardiovascular risk factors are another particular concern for MS patients because they are also brain risk factors. Diabetes, hypertension or high cholesterol makes MS worse, and these patients need wellness and preventive care even more than the average person, said Dr. Rudick.

Divvying up duties

The division of responsibility for those other medical problems can be complicated for patients who are in close contact with their specialists. “What happens a lot of the time with MS neurologists is we become patients' primary care physicians and that doesn't really need to happen. We can strictly manage their MS with MS-specific therapies,” said Dr. Houtchens.

Even some MS-related problems can fall under the umbrella of the general internist. “They just require someone who takes the time to listen to the symptoms and prescribe common treatments. So, for example, fatigue can be treated with medications and physical therapy and fitness,” said Dr. Rudick.

Whether or not one can treat the problems in primary care, eliciting them is crucial, said Jonathan Feeney, MD, a family physician who treats MS patients in Vail, Colo. “Have enough knowledge to ask the right questions: Are they having issues with their bladder? Are they having issues with depression? Ask the right questions to get them to the right specialists.”

Many questions are likely to relate to medication. Current injectable therapies for MS have side effects and require monitoring and those issues will likely increase with the advent of oral therapies. The FDA is reviewing at least one oral medication for MS, while others are in the pipeline, some on the fast track.

The benefits of these new drugs are being debated among specialists. “They actually appear to be slightly riskier than some of the drugs we have now. There will be the choice of riskier oral [medications] versus less risky, established drugs with longer-term safety information that are injectable,” said Dr. Cross.

What's not debated is that the oral medications will require the attention and cooperation of internists and MS specialists, “a much more comprehensive approach to managing the patient,” said Dr. Markowitz.

“Find a neurologist who really enjoys and sees MS as an important part of practice and establish a relationship to give the patient the best care in a coordinated manner,” Dr. Feeney said.