Cardiac care critical for diabetic patients

Even the experts feel like they're missing potential cardiological complications in diabetic patients. They consider how to screen this population effectively for the 3% of patients who experience cardiac-related deaths.

When cardiologists Frans J. Th. Wackers, MD and Lawrence H. Young, MD, began a trial screening asymptomatic diabetics for coronary artery disease (CAD), they were hoping to reduce the number of surprise cardiac events in these patients.

“As cardiologists, we all felt that we were missing things in patients with diabetes. They often come in with advanced coronary artery disease,” said Dr. Wackers, professor of diagnostic radiology and medicine at Yale School of Medicine. “They often do not have symptoms of angina. Sometimes people come in with an infarct when you see them for the first time.”

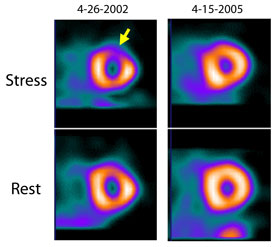

However, Dr. Wackers was surprised by the results of the DIAD (Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics) trial, published in the April 15, 2009, Journal of the American Medical Association. The trial randomly assigned 1,123 patients who had type 2 diabetes and no CAD symptoms or history to usual care or screening by myocardial perfusion imaging. After five years, researchers found no significant differences in myocardial infarctions, cardiac death or revascularization between the screened and unscreened patients.

“I thought that trying to pick up disease earlier would actually translate to more invasive therapies and better outcomes in the screened group,” explained co-author and endocrinologist Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, a professor of medicine at Yale.

On the contrary, the study found that using a nuclear stress test to screen every diabetic patient is not an effective strategy. But it left wide open the question of how to isolate, among the millions of Americans with diabetes, the patients who are at particularly high risk for a cardiac event.

Needle in a haystack

The good news from the research is that surprisingly few heart attacks and cardiac-related deaths occurred in either group. “The overall event rate was much lower than we anticipated. We expected it would be 8% or 10% and it was only 3% over 5 years,” said Dr. Wackers.

The miniscule overall cardiac event rate of 0.6% per year made it very unlikely that the screening could prove worthwhile. “If you calculate what it would cost to screen the entire group of patients with type 2 diabetes, it would be billions of dollars,” Dr. Wackers said.

Of course, if you could find some way to narrow the screened population and further risk-stratify the diabetic patients, screening for CAD could potentially be more cost-effective. But the experts disagree on the feasibility of accomplishing this stratification.

Dr. Wackers contends that screening will never be cost-effective because the cardiac event rate is already so low. “Selecting patients by additional risk factors or another screening test wouldn't make enough of a difference,” he said. “The outcome of these asymptomatic patients is already good with contemporary therapy. It's very hard to do much better.”

But Dr. Young, first author on the JAMA paper and professor of cardiovascular medicine at Yale, isn't ready to give up. “Though it's a small number, we would like to eliminate those heart attacks and deaths. We need to understand a little bit more about the patients who died.”

By doing an in-depth analysis of the patients who did have cardiac events in the study, he and his colleagues hope to identify meaningful predictors of heart attack and cardiac death (potentially traditional clinical ones like cholesterol, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein or some new physiologic measurements). “We'd like to put together a profile of patients who are at high risk and then figure out whether focusing on those patients with screening and advanced treatment might be beneficial,” Dr. Young said.

A screening alternative

Some cardiologists think they've already found the right test to uncover those higher-risk patients—coronary calcium scanning.

“It's a 30-second test. There's no IV, no contrast. It's very, very simple,” said Seth Uretsky, MD, director of the cardiac CT and MRI program at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York, who spoke at Internal Medicine 2009 about CAD screening for diabetics.

Although there haven't been any large, randomized trials of calcium scoring as a screening tool, research has shown it to be very predictive of cardiac events, especially in the diabetic population, said Daniel S. Berman, FACP, chief of cardiac imaging and nuclear cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

“A proposal that would make sense would be to take diabetics who are in the 50- to 75-year-old age range and test them with coronary calcium scanning. If they have coronary calcium scans that show a score of more than 400, then they'd be excellent candidates for a myocardial perfusion scan,” Dr. Berman said.

Dr. Uretsky favored further testing for diabetic patients with a score over 100, but his reasoning was the same. “What you'll see is your number of normal stress tests will shrink and your ischemic stress tests will increase. You're going to be performing stress tests in the right patient population,” he said.

Not all the experts are so enamored of coronary calcium scanning. “I caution what this test does not do,” said cardiologist Helene Glassberg, MD, assistant professor medicine and cardiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, in another session at Internal Medicine 2009. “It does not identify the morphology of the plaque. It doesn't identify soft plaque at all and it doesn't identify the presence or absence of obstructive disease.”

Dr. Young also has his reservations. “There's no question that calcium scoring would enrich the population for those with more advanced atherosclerosis, who as a group are at increased risk, but whether millions of diabetic patients should be subjected to CT scans will need to be evaluated,” he said. “Before routine CT scans are advocated, additional research would have to prove that this alternate screening strategy coupled with additional interventions actually prevents heart attack and cardiac death in asymptomatic patients.”

Dr. Berman agreed with the need for further study, although he thinks internists should put his proposal into practice now. He did note one other problem, reimbursement for the scans. “In some states, it's covered by Medicare for patients who have two or more risk factors—and one of those would include diabetes—but in most states it's not,” he said.

Even if it were covered, the potential societal cost of testing seemed problematic to Dr. Wackers. “If you would give every patient statins, then in the end it would be cheaper to do that and now you're not missing anybody. Testing is not perfect,” he said.

The rest of the patients

But is medication perfect? All of the experts agreed that the low event rates found in the DIAD study were likely due to the increase in use of preventive medical therapy—aspirin, statins, ACE inhibitors.

After all, it's become a mantra of diabetes care: treat all diabetic patients as if they have heart disease. But that recommendation appears to negate the whole question of screening, noted Dr. Uretsky. “If we're treating diabetics as if they have CAD, why would you screen diabetics for CAD?”

The answer to his question lies in the gap between recommendations and reality. In practice, diabetes is not always actually treated as a CAD equivalent. “Although we try to treat all diabetic patients to these goals, in fact compliance is not very high,” said Dr. Berman.

“The truth is if you took all diabetics in this country and treated them correctly as if they had coronary disease, that would be a huge burden—a time burden on internists and cardiologists,” Dr. Uretsky said.

It's also a burden for patients, according to Dr. Berman. “It's not really fair to treat all diabetics the same. Reaching a goal of 70 [mg/dL] for your LDL cholesterol is difficult for many patients,” he said. Statins can have problematic side effects for patients, and the idea that one has the equivalent of CAD is a serious psychological burden.

Thus, while most of the screening focus has been on picking out the high-risk patients, there's also value in using tests to identify the low-risk patients, Dr. Berman said. “We need to know as physicians which patients really need to meet [a low LDL] goal and which patients do not. I think it's reasonable for us to consider less stringent treatment goals for diabetics who have no coronary calcium.” Study data has shown that more than a third of asymptomatic diabetics have little to no coronary calcium, Dr. Berman noted.

While good screening results can be a comfort, bad ones can serve as a motivator. “Being able to demonstrate to a patient that they not only have the risk of coronary disease but that they actually have the disease in their arteries and their heart can be a more effective motivator to getting people to comply with their medical treatments,” said Dr. Berman.

Current practice

Those patients who worry their physicians, along with those who worry themselves, are most likely the ones who are currently getting myocardial perfusion imaging in the absence of symptoms, the experts said.

“Maybe there are a few extremely worrisome asymptomatic patients, like a person who is sedentary, still smoking and has a cholesterol that's just off the wall and doesn't tolerate statins,” said Dr. Young.

This use of scans particularly in less evidence-based situations such as executive physicals will likely be affected by the DIAD results, he continued. “I think physicians will have a higher threshold for ordering screening stress tests.”

The higher threshold is still highly nebulous, though. “Some doctors might have a sixth sense about some patients that have multiple risk factors and may have had multiple family members with early disease onset. You really have to use clinical judgment and your sixth sense about whether to screen an individual patient,” said Dr. Inzucchi.

Of course, the decision about nuclear stress testing is very different for people with diabetes and symptoms of CAD, patients for whom internists should be on the lookout. “They've got to probe a little bit because if a patient is having symptoms, then they are in a very different risk category,” said Dr. Young.

“If you have a patient with diabetes, you should very carefully speak to this patient and find out if they have any cardiac symptoms. Do a physical exam and look at an electrocardiogram,” advised Dr. Wackers.

Patients should also be educated on the importance of noticing symptoms and seeking attention for them, the experts said. And then it's OK for physicians and patients to take a minute to enjoy the good news of the study, Dr. Young said.

“There's been a lot of doom and gloom about heart disease in diabetes. Although it is a very serious problem, one of the take-home messages from DIAD is that asymptomatic patients do pretty well with contemporary medical preventive therapy and careful surveillance for cardiac symptoms.”