Practice hassles have more docs going locum

Economic factors and bureaucratization are prompting more internists to adopt locum tenens employment as a career path. Read the stories of doctors who have made the switch successfully.

The life of William A. Kern, FACP, might not strike most people as a pleasant retirement. In February, he was working in an outpatient practice on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota where the temperature had been hovering below zero for weeks. Both of his colleagues were out sick, one in the hospital, and many of his patients were seriously ill, too.

But just a few weeks before, he had been covering a low-pressure schedule at a mental health institute in Virginia. And in the next couple of months, Dr. Kern would be vacationing in Madrid, attending a conference in Philadelphia and traveling around Eastern Europe.

Such is the life of a modern locum tenens physician. As Dr. Kern puts it, “Anyway, it's varied. It's interesting.”

Escape from paperwork

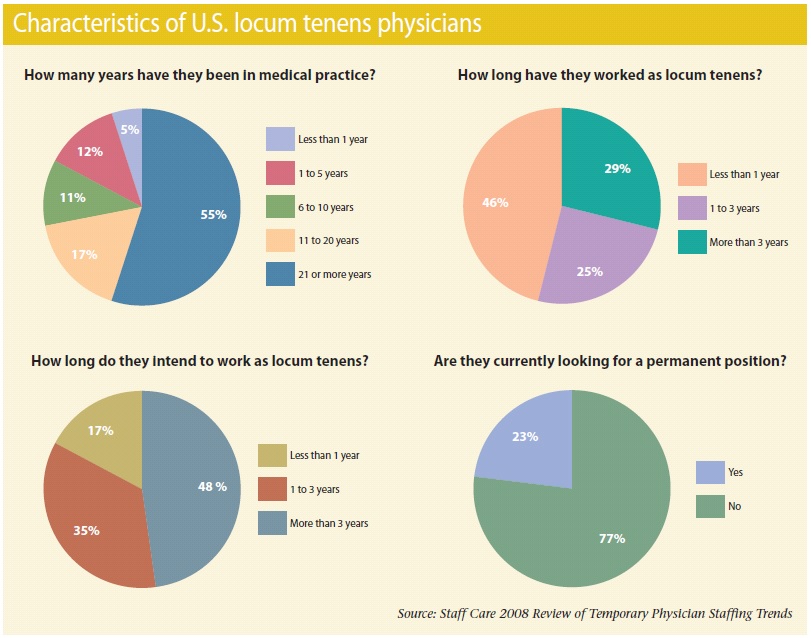

From the economic crisis to the bureaucratization of primary care, a number of factors are causing internists to look at locums as a career option, whether they're “retired” like Dr. Kern or fresh out of residency. (See the trends in Figure.)

Last year, a survey by the Physicians' Foundation found that 49% of primary care physicians were thinking of leaving or cutting back on practice, and that increased time dealing with non-clinical paperwork, difficulty receiving reimbursement, and burdensome government regulations were their top complaints.

Some of those frustrated docs are finding locum tenens to be the solution to their problems. “We hear, not only from primary care doctors but across the board, that the reason they turn to locum is that they're ready to just practice medicine again versus deal with all the insurance hassles, overhead, billing—all the hassles of having a private practice,” said Aaron Ray, vice president at Staff Care, a locum tenens agency.

That's how George H. Johnson, Sr., DO, entered the field after retiring from his internal medicine private practice in 2003. “I got terribly disenchanted with things as they were,” he said. “When I went to medical school, you were taught to take care of the patient. The livelihood and so on were forthcoming.”

Today his “livelihood and so on” is in the hands of a locum tenens agency, Whitaker Medical. “Now I do medicine—period. I don't have to worry about anything except taking care of the patient, as I was taught,” said Dr. Johnson.

Over the past few years, he's practiced in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Missouri, Arkansas and his home state of Texas, with placements ranging from two days to much longer. “I took an assignment at a federal prison and I was there about four months,” Dr. Johnson said.

The length of that assignment reflects one of the ways that the locum tenens field has changed in recent years. “It used to be some vacation coverage here and there and maybe some maternity coverage or sick leave and now it's really become a way to practice medicine,” said Mr. Ray.

Long-term locums

Employers are increasingly looking at locum tenens as a solution to permanent vacancies, in part because of physician shortages, but they also see the appeal of trying out potential employees before making a hire, Mr. Ray explained. A 2007 survey by Staff Care found that 65% of their customers were hiring locums tenens to fill in until a permanent doctor is found, compared with only 36% in 2004.

Jason Haddad, vice president for locum tenens firm Jackson & Coker, has seen a similar trend. “Many clients right now are looking to use locum tenens instead of making that permanent, long-term commitment. They want to test-drive a physician first before they hire them. They'll try out one of our physicians for a few months, and will then purchase their contract from us if it's a fit,” he said.

John Ho, MD, learned first-hand that locum tenens can lead to a good fit in a permanent position. He had been working as an infectious disease researcher and associate professor when his job ran out of research funding.

“It was an awkward time and place,” he said. His plan was to become a hospitalist, but he decided to start out by signing up for locum tenens. “I didn't know whether hospitalist work would suit me, even though on paper it looked good. I didn't want to commit myself.”

Over the next year, he worked at two hospitals in Maine, both of which offered him a permanent job. “They were short-staffed because patient volume had significantly grown,” Dr. Ho said.

Although neither hospital was the right fit (too far from his young family), Dr. Ho decided that the role was, and he eventually found a hospitalist job closer to home. The differences in the two hospitals' size, patient census and environment provided background for his selection of a permanent hospitalist position.

“[Locum tenens] is a perfect avenue for a physician to learn about what they want to do,” said Mr. Haddad. The growth in the field is gradually bringing about a change in mindset about how physicians choose a job, he added. “Although, we do still encounter physicians who are not familiar with locum tenens. They think that when you come out of residency you're supposed to immediately take a permanent position, and that's where you are for 30 years.”

Alice So, MD, epitomizes the new, alternate model of medical practice. When she finished her internal medicine residency in 2005, she was interested in becoming a cardiologist, but found that she would have to wait a year to get into a fellowship.

“I was trying to figure out what to do with my life,” she said.

Dr. So looked at locums then, but ended up going into business consulting in malpractice cases. After spending several months establishing her business she turned to locums again.

She's been at her current hospital for two years, which might not even sound like locum tenens to some, but Dr. So values the freedom to pick up and go when she's ready. She's declined permanent job offers from each of her placements.

And she appreciates not being forced to settle down in the locations where the best jobs are available. The native New Yorker is currently practicing in New Hampshire. “The beautiful thing about locums [placements] is that the hospitals are great places to work, but the areas are not where I want to settle down,” said Dr. So.

Money matters

The lifestyle has its downsides, however, Dr. So noted. “There are no health benefits. There's no 401(k) and there's no guarantee that you'll have a job after the next three months.”

Despite those sacrifices, the finances of locums can be an improvement over other options. Some older physicians (55% of docs in the Staff Care survey had spent 20 years or more in practice) have moved into the field as they saw the profitability of their practices dwindle, said Karla Wild, MD, a locum tenens pediatrician who is also medical director for Whitaker Medical.

“In order to keep your head above water and just pay your office expenses, you had to see 30 to 40 patients a day,” she said.

As a locum tenens, she enjoys setting her own rules for practice. “You go in and see the patients and you can structure your hours. You don't have to work every day. You don't have to be on call and go to hospitals if you don't want to,” she said.

The employers of locum tenens physicians are willing to provide reasonable schedules and pay a premium (the top drawback cited by locum employers in the survey was cost) because the physicians turn a profit for them, noted Mr. Ray. “It makes sense if a hospital or a practice does not have a permanent physician to put a locums in. Not only are they generating revenue, but they're continuing to keep their patient base up,” he said.

Just as hospitals are seeing locums as a more long-term option, so are some physicians. The Staff Care survey found that 48% of locum physicians were planning to spend more than three years in the field.

As long as a physician is relatively flexible, it's entirely possible to put together a full-time schedule, said Mr. Ray. “If a physician were to come and say, ‘I want to work full-time as a locums but I want to work just in Dallas,’ it would probably be difficult, though it wouldn't be out of the realm to keep them busy.” But for someone who's willing to travel and try out diverse practice settings, there are plenty of opportunities, he said.

Economy takes a toll

The number of locum job openings has dwindled slightly in recent months, said Mr. Haddad. “Of course, with the economy recently, there has been a slight decline in jobs. I think that's pretty natural. Primary care has been a little bit better off than some other specialties,” he said.

Edward McEachern, vice-president of marketing for Jackson & Coker, speculated that some of the drop could be due to the individual financial decisions of non-locums docs. “When a doctor's 401(k) is worth half of its original value, he may not be willing to take as many vacations and electing to work through his vacation. That closes a locums opportunity,” he said.

Paying for retirement is a driver of supply, as well as demand, for locums. Armando Espiritu, MD, an internist from Port Arthur, Texas, enjoys the practice and the travel of occasionally working as a locums, but the primary appeal was financial. “After I retired five years ago, I felt the need to supplement my retirement savings. I have this constant anxiety that we may run out of money if we—my wife and I—live long enough,” he said.

Since the economic crisis hit, other physicians appear to be following his lead. “As far as the physician side, as the jobs are getting a little bit lower, there seems to be a little more interest from the physicians,” said Mr. McEachern.

Not that any physician interested in locums should be concerned about finding a job, the recruiters said. “I see locum tenens continuing to be a big part of medical practice—more people doing it, and more people using it,” said Mr. Ray.

Dr. Kern will continue to be one of those people for the foreseeable future. Like everyone else, he's seen his retirement account dissolve, but that's not why he continues to practice medicine wherever and whenever, as long as it doesn't conflict with his vacation schedule.

“I felt like I still had enough brains to do this and physically I'm in pretty good shape,” he said. “You turn the world upside down. You take your time off and let the work fall in between.”