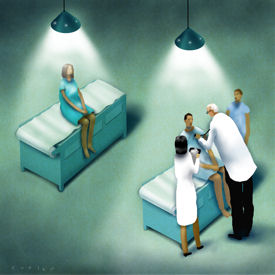

Gender gap increases women's heart risks

Nearly half the time, the first clue a physician gets that a woman has heart disease is that she drops dead. Updated guidelines now dictate physicians should first screen for a woman's risk factors for heart disease by age 20.

Nearly half the time, the first clue a physician gets that a woman has heart disease is that she drops dead.

If that's not a wake-up call to increase detection of cardiovascular disease in women, nothing is, said C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD, director of the Women's Heart Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“It used that be that more than 50% of men presented with sudden cardiac death, while women were down around a third,” Dr. Bairey Merz said. “But women have popped up to about 50% in the last decade.”

What's more, all-cause mortality from coronary heart disease, which steadily declined for two decades starting in the 1980s, began to increase again in women in the 2000s—particularly for women aged 35-44 years old. Rates leveled off for men, but didn't increase.

There are numerous and complicated reasons for this discrepancy, but at least some of the blame rests on the shoulders of physicians, Dr. Bairey Merz said. Indeed, a February 2005 Circulation study found physicians were 40% less likely to identify female than male patients at high risk for heart disease—even when they had the same risk factors as the men. Women with known heart disease are also less likely to be given preventive aspirin and statins than men, several studies have shown.

“The data suggest there is a disconnect in the way physicians diagnose and treat heart disease in women versus men,” Dr. Bairey Merz said. “It also appears there is a blockage at the primary care level, that women aren't getting adequately evaluated and referred.”

Such data must serve as a call to awareness, experts said. Physicians need to catch risk factors in female patients while there's still time to prevent them from developing heart disease.

What Framingham leaves out

The Framingham Risk Score is often cited as the gold standard for evaluating a patient's risk of having a heart attack or dying from heart disease. Its formula uses age, LDL and HDL cholesterol, blood pressure, cigarette smoking, and diabetes mellitus to estimate a 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

“The Framingham makes it pretty easy to detect heart disease in a woman,” said Elizabeth Barrett Connor, MACP, chief of epidemiology in the family and preventive medicine department of the University of California-San Diego School of Medicine. “Unlike a lot of research out there, women were included in the Framingham study from the start.”

Yet there are risk factors left out of the Framingham calculation that many experts believe should be included in a woman's overall profile.

“I use the Framingham, but the problem is that some people will come out relatively low on the score and still have a big risk factor, like family history,” said Vera Bittner, FACP, section head of preventive cardiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “I'm going to look at someone differently whose father had sudden cardiac death at age 41, whose brother has a stent and whose first cousin has a defibrillator, compared to a person with none of these.”

The Framingham score also doesn't take C-reactive protein levels into account—a factor that some experts view as critical in assessing risk, especially in postmenopausal women.

In an April 2007 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. Roger Blumenthal, ACP Member, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and colleagues noted that a high C-reactive protein level (greater than 3 mg/L) can double a woman's risk of arterial disease. So can family history, they noted, pointing to another article in the same issue of JAMA which reviewed the predictive value of more than 35 risk factors not included in the Framingham.

An antidote to the Framingham could be the Reynolds Risk Score, which is similar in brevity but is meant only for women, and includes C-reactive protein and family history of heart attack in its formula. Like the Framingham, the calculator also asks about a patient's age, smoking, blood pressure and total and HDL cholesterol levels.

“The Framingham will only correctly pick out which of two people will have a heart attack or die from heart disease 70% of the time,” said Kristin Newby, MD, a cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center. “The Reynolds is a stronger model, because it is basically the Framingham with additional things added—family history and C-reactive protein. But no predictive model is going to be perfect.”

A drawback of both the Framingham and Reynolds risk scores is that they only provide 10-year risk estimates. To address that shortcoming, as well as account for new research, the American Heart Association updated its Guidelines for Cardiovascular Prevention in Women in 2007 to encompass risk over a woman's entire lifetime.

Identify risks early

Physicians should first screen for a woman's risk factors for heart disease by age 20, the updated AHA guidelines say.

“By getting a baseline at age 20, or at least in the early 20s, we pick up on problems, like cholesterol or family history, that we might otherwise miss and which can change the course of a woman's health,” said Dr. Newby, who helped write the guidelines.

In a nutshell, the guidelines say to evaluate risk by taking a medical and family history; asking about symptoms of cardiovascular disease such as angina; doing a physical examination that includes blood pressure, body mass index and waist size; taking labs that include fasting lipoproteins and glucose; doing a Framingham risk assessment in women with no cardiovascular disease or diabetes; and doing a depression screening in women with cardiovascular disease.

Based on the outcome of the evaluation, a woman is placed in a category of “high risk” (such as having diabetes, established coronary heart disease or a Framingham score of greater than 20%); being “at risk” (such as being a smoker and/or obese) or “optimal risk” (having a Framingham score of less than 10% and a healthy lifestyle). Prevention recommendations then vary based on a woman's risk level.

The guidelines don't say how often to evaluate a woman's risks, and experts disagree on that point. Some say it should be done at each annual visit; others say every five or 10 years is fine, as long as the woman has demonstrated low risk thus far.

Rowena Dolor, ACP Member, director of the Primary Care Research Consortium at Duke University Medical Center, said primary care physicians should run through risks at each annual visit. Yet most PCPs probably won't do this, and if they do, they won't hit every single item in the guidelines, she said.

“Most of us will do a physical exam, take blood pressure, measure weight and height, and check a lipid panel. Providers don't usually measure waist size in all individuals or perform depression screening in patients with known heart disease,” Dr. Dolor said. “My sense is that most providers don't calculate the Framingham, either.”

Suzanne Steinbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, agreed.

“Most people don't know about the Reynolds Risk Score, and I'm thrilled if they even do the Framingham,” she said. “Usually what I see is that a cholesterol test will be done, but doctors won't go through the steps of actually calculating a person's risk of heart disease.”

Granted, said Dr. Dolor, research has shown primary care doctors don't have time to follow every single guideline to the letter. She pointed to an April 2003 article in the American Journal of Public Health that found physicians would need to spend 7.4 hours every day on prevention in order to meet all the recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

“It's true, everyone is busy,” Dr. Dolor said. “But we could accomplish most of these (women's heart guidelines) in primary care without much extra effort.”

In the case of a seemingly healthy woman, a guidelines-based risk evaluation only needs to be done every 5-10 years, opined Dr. Newby—and that isn't too much to ask of a physician.

“I don't think checking someone's cholesterol or calculating a Framingham Risk Score every decade is a huge burden on primary care doctors or cardiologists,” Dr. Newby said. “A lot of this you can do by looking at the data the nurse already collected from the patient, then asking a few key questions.”

Overlooked, but important

Some of the risk factors that primary care doctors are apt to skip over are the most important ones to look into, experts said.

“We sometimes forget to ask whether a woman is exercising, and if she's not, why not,” Dr. Dolor said. “But if I find out that a woman isn't exercising because she gets tired faster than she used to, that is a hint to ask more questions about exercise capacity and see if this may be due to a heart or lung condition.”

Smoking is another big one to ask about and follow up on, said Dr. Newby. Smoking rates among young women are rising faster than for other segments of the population, including young men, so doctors need to stay on top of patients and connect them with resources to help them quit. The same goes for second-hand smoke, Dr. Dolor noted. Cohort studies have shown secondhand smoke exposure increases the risk of heart disease, as well as cancer and stroke.

Stress, anxiety and hostility levels can also increase a woman's risk of heart disease, several experts noted. Indeed, the September 2004 INTERHEART study (published in The Lancet), which evaluated differences in heart disease risk by gender, found that exercise, good nutrition and the absence of stress and depression had greater protective effects against heart disease for women than men.

“These are some differences that make it all the more important to take five minutes to ask about exercise and diet and stress and anxiety, particularly in women,” Dr. Newby said. “Not that we should ignore these in men, but it is of particular importance in women.”

Diabetes, too, has a particularly strong effect on women's hearts—so strong that it cancels out the estrogen protective effect in premenopausal women and eliminates the 10-year lag women typically have versus men in developing heart disease, experts said.

“If you have a diabetic woman, you should treat her as if she is at an intermediate risk of heart disease even if she is eating well and exercising,” Dr. Steinbaum said. “She should really have stress testing done.”

Studies have indicated women are less likely than men to be referred for testing after initial risk factors are unveiled—a trend primary care doctors need to be aware of in order to correct.

“A woman at high risk needs aggressive intervention—she needs to be referred for a stress test and an angiogram, and managed aggressively. An intermediate-risk woman needs to be further risk-stratified by an imaging test,” Dr. Steinbaum said. “You know, unlike many other diseases, heart disease is something you can really prevent. So the earlier you start, and the more persistent you are, the better.”