Physicians not content to stick with the status quo

Health care access has become a top issue in 2008.

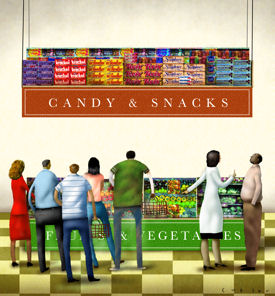

Physicians often struggle to get patients to eat healthier, exercise more, or take their prescribed medications, even though these actions would appear to be in the patient's best interests. But, according to recent research in the field of behavioral economics, most people do not make rational decisions based on the best evidence available. Take a patient who is battling obesity, for example. You can arm the person with studies, statistics and nutritional advice but that person may still stop for a Big Mac on the way home, opting for surefire immediate gratification over less tangible long-term rewards.

People also tend to be creatures of habit, preferring to maintain the status quo even if they would benefit from change, researchers have found. How can physicians use this information? According to Stacey Butterfield's story, they can make it easier for patients to choose wisely by presenting desired responses as default options. For example, make HIV testing routine for all patients or automatically schedule seniors for flu shots, forcing patients who object to the procedures to actively opt out. Worried that patients will forget to call for a follow-up visit? Schedule the visits automatically, making that the path of least resistance.

These techniques still need testing and of course, being new, require physicians to resist the tendency to stick with the status quo. But there's evidence that some physicians are willing to break the mold. “It takes work to design an office with patients at the center,” looks at how some physicians are dealing with the practical aspects of implementing patient-centered care. Changing the way they interact with patients is only one piece of the puzzle, two physicians interviewed for the article found. Equally important is getting staff on board with change and implementing systems to record and track patients' progress.

Also in this issue, look for highlights from the American Heart Association's International Stroke Conference. Jessica Berthold, who attended the conference, also takes an in-depth look at the need for stroke education in primary care offices. New research presented at the conference found that nearly a third of primary care office receptionists would tell a caller reporting classic stroke symptoms to come in for a visit rather than call 911. With timely treatment so important to stroke recovery, it makes sense to make sure your front-office staff is educated and prepared to respond.

Some of you may have read our sister publication, ACP Hospitalist, a monthly magazine offering news and features on issues relevant to hospital medicine. Recently, we also launched an e-newsletter, ACP HospitalistWeekly, a summary of news highlights delivered weekly by e-mail. If you'd like to receive ACP Hospitalist in the mail or via email (or both), please drop us a line. Enjoy the issue and I look forward to hearing your comments.

Sincerely,

Janet Colwell

Editor