Virtual lounge connects far-flung physicians seeking advice

It wasn't cancer or a broken bone, but it was a nagging problem that wouldn't go away: The Case of the Burning Lips.

It wasn't cancer or a broken bone, but it was a nagging problem that wouldn't go away: The Case of the Burning Lips.

Unsure of the cause, the victim's doctor appealed to his colleagues, sharing a close-up photo of the patient's lips and a medical history. About 60 doctors agreed with his diagnosis of contact dermatitis and the prescription of a topical steroid. Yet the burning persisted.

Then a colleague, noting that the patient was on Dilantin, asked if she may have recently switched to the generic version, phenytoin. Some of his patients who had done so also complained of burning lips, he explained. And with that, the mystery was solved—without a single participating doctor ever having met face-to-face.

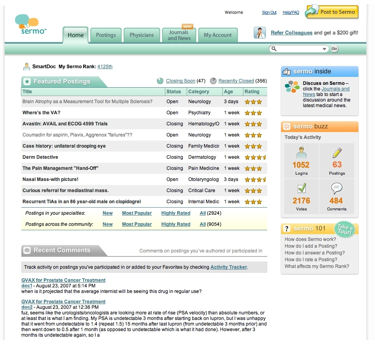

The entire exchange took place on Sermo, a free online network that lets doctors ask and answer clinical questions, read and discuss medical news, build profile pages and send private messages—all anonymously, if they so choose. Medical credentials are rigorously checked before doctors can join.

There are no advertisements, as the site makes money by letting businesses access content (without seeing users' identities). Pfizer has paid handsomely for its clearly-labeled company docs to participate in site discussions, while hedge funds have forked over to find out which drugs are hot or not with physicians.

Other online networking sites for physicians exist, but Sermo (Latin for “conversation”) is by far the largest. Surprisingly, its more than 43,000 users are not predominantly fresh-faced residents with MySpace or Facebook accounts: Doctors age 45 and older outnumber younger users three to one, says Sermo founder, Daniel Palestrant, MD.

It makes sense, when you think about it. Older doctors were weaned on the sort of clinical exchange of ideas that took place in hospital lounges and hallways, then watched as this practice declined when practitioners split off to form smaller outpatient groups or solo practices. No wonder they jumped at the chance to recreate the good old days.

Teri Willochell, MD, a general internist in Pittsburgh who has been a Sermo member since its September 2006 launch, says she loves how the site has brought back the camaraderie doctors used to feel when they worked elbow to elbow.

“I work in an outpatient facility, so I don't get exposed to the whole inpatient scene,” Dr. Willochell said. “Sermo is one big learning experience. I read about new drugs there first—before I see it in a journal—and I'm much more educated about politics in medicine because of it.”

She especially likes how responsive the site is to user feedback, with its “wish list” for users to suggest changes.

“It seems like every time we come up with something, they improve it. We want spell check—boom!—they put spell check on. We want instant messaging—boom!—it's there,” Dr. Willochell said.

Initially, doctors used Sermo mostly to talk about political issues, or to socialize with one another. Increasingly, however, the site is used to discuss clinical diagnoses in real time, Dr. Palestrant said.

“The most emotional part of Sermo is that you see doctors posting clinical scenarios and in a matter of hours, dozens of other physicians are collaborating to improve patient care,” Dr. Palestrant said.

Dr. Willochell used Sermo to help decide how to deal with her child's sleep apnea, treat a patient who had endometriosis on a sciatic nerve, and find out if doctors actually use duct tape on plantar warts. (They do.)

Posts are ranked on popularity, with the most popular featured most prominently on the site. Doctors are ranked based on how others respond to their posts, as well.

“We don't have any editorialization or moderating of the site,” Dr. Palestrant said. “We rely on peer corroboration to make the good things rise to the top.”