Assessing BMI, waist size vital to prevent worsening obesity

Body mass index and waist circumference are at the core of diagnosing obesity, yet these measurements are often bypassed in the typical office visit.

Body mass index and waist circumference are at the core of diagnosing obesity, yet these measurements are often bypassed in the typical office visit. That omission may seem unneeded in diagnosing the obviously obese but it's vital to flagging those at risk before their weight becomes a problem.

Identifying patients with a health-harming weight problem clearly falls into the bailiwick of general internists and other primary care physicians. In the last decade, practice guidelines from the ACP, National Institutes of Health and from Canada to Australia have called on doctors to screen, measure and record. Without measurement, counseling doesn't occur, treatment isn't initiated and prevention isn't preached.

“The literature is very strong that it's not until the patient is moderately to severely obese and/or has multiple medical problems that the doctor pays attention to weight,” said Robert F. Kushner, FACP, professor of medicine at Northwestern University. “And the missed opportunity is called prevention.”

Dr. Kushner, the primary author of the AMA's “Assessment and Management of Adult Obesity” primer for physicians, continued that, “People with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 are obese, a level that approximates 30 pounds overweight, but doctors don't even pay attention to someone like that.”

Moreover, added Louis J. Aronne, FACP, clinical professor of medicine at Cornell University, past president of the North American Association for the Study of Obesity, and editor of the NIH/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute guide to obesity treatment, doctors shy away from diagnosing something they don't know how to treat.

“They know what to do when they get a measurement that shows high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol,” he observed. “But how do they treat obesity? They don't have the tools yet. So, they avoid it and wait for these other things to develop.”

BMI isn't guesswork

The first step in identifying overweight and obese patients is getting an accurate weight, then measuring height. It doesn't have to be done annually, but calculating and charting the patient's BMI should occur with every new patient and every few years for everyone else. An online BMI calculator is available. All guidelines state that BMI—not weight alone—is needed for diagnosis. It's been the standard of care since 1985 when it was adopted by the NIH, Dr. Kushner said.

According to Caroline Apovian, FACP, an associate professor in medicine at Boston University's weight management center, “We obesity experts have been saying for years that BMI (body mass index) and waist circumference should be vital signs just like blood pressure and pulse, but I know it doesn't happen all the time.”

The goal is to screen for people at risk for diabetes, high blood pressure and stroke. BMI may not accurately measure body fat, she said, but it is an extremely accurate predictor of these risks.

Guesswork doesn't work. Studies prove physicians are poor at deducing BMIs. The December 2006 issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons found that health care providers misclassified BMI by 32% when they estimated patient height and weight.

Asking patients is better, but not much; people notoriously underreport their weight and overstate their height.

“You can't tell if a BMI is 28 or 32 just by looking at the person,” said Arya Sharma, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, scientific director of the Canadian Obesity Network and an author of Canada's obesity clinical guidelines. “You won't know if your patient is actually responding to your treatment if you aren't going to measure it.”

Obtaining even the most basic measurement—weight—also isn't problem-free. A common problem is not having a big enough scale in the office to weight severely obese patients.

“It's a huge problem in my office, and it's incredibly embarrassing not to be able to get an accurate weight,” said Vincenza Snow, FACP, an internist in Philadelphia, Director of ACP's clinical programs and quality of care, and author of the College's obesity treatment guideline. “What we usually do is write in the chart ‘over 350.’”

But writing ‘over 350’ is dangerous,” Dr. Aronne said. It means doctors miss the chance to encourage their extremely obese patients who lose a few pounds to keep on with their hard work. It also means doctors allow weight problems to worsen.

Dr. Aronne recalled one of his patients who came to him after five years of being charted by her primary care physician as over 350. “When I saw her and we weighed her on our scale that goes up to 880 pounds, she weighed over 500 pounds. She had been allowed to gain 150 pounds,” he said.

Given the number of obese Americans—the CDC reports that nearly one-third of adults are now obese (with BMIs of 30 or above), up from 15% 30 years ago—obesity specialists contend that all primary care offices should have large scales on site.

“You are going to see these patients,” Dr. Sharma said. “It's doesn't look very professional to say you have to go somewhere else to get weighed because my office unfortunately doesn't have a couple hundred bucks to buy a scale that actually works.”

Waist size matters

After calculating and charting BMI, doctors should also measure patients' waist circumference regularly. That standard has been part of most national guidelines for nearly a decade but, since waist circumference tracks closely with BMI, some obesity specialists argue that little is gained by measuring waists as well. Others contend that it is a useful measure of cardiometabolic risk for overweight people with BMIs lower than 40.

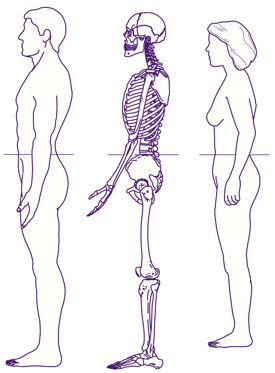

“You can have two people the same age, the same gender, and the same weight, and yet have two different risk estimates based on where the fat is located,” Dr. Kushner said. Identifying excess abdominal fat is particularly important, he said, because it has been shown to be one of the clinical features of metabolic syndrome.

A study published this summer also found a correlation between waist circumference and enlarged prostates and raised PSA levels in men. Other researchers contend that since BMI is less predictive for elderly people because of the loss of fat-free mass with increasing age, waistline measures or a waist-hip ratio may be more useful for the elderly.

Although earlier literature had called for calculating waist-hip ratios to determine this additional risk, most evidence supports the view that waist circumference alone “is just as robust” a risk predictor.

Waist circumference is sometimes bypassed because physicians and nurses are less familiar with doing it and do not have protocols in their office, Dr. Kushner said. First, every exam room should have a tape measure, and then staff needs education on how to measure waist circumference consistently. Measurement should be at the level of the iliac crest and should be taken at the end of a normal expiration of breath.

Excess abdominal fat is defined at more than 40 inches (102 cm) in men and 35 inches (88 cm) in women. When a BMI exceeds 40, measuring the waist circumference is unnecessary, because it will always fall into the “excess” category. A safe waist-hip ratio for men should be less than 0.9 and for women less than 0.8. In general, carrying excess weight around hips and thighs (being “pear-shaped”) carries less health risk than sporting it around the middle (“apple-shaped”).

Finally, obesity specialists said primary care physicians do not need high-tech methods to measure body fat. Dr. Aronne concluded that MRIs of the abdomen or measures of fat inside the liver “may tell us where fat is, but they don't tell us more about risk.”