Cuba is just across the water, but medically, a different world

ACP Member Paul Drain explored Cuba's medical system and finds primary care broken down much differently than in the U.S., with more access resulting in less of a need for inpatient care. But the politics of re-establishing relations with the country are no less tenuous today than they've previously been.

It's been 50 years since Cuban and U.S. physicians have had much contact with each other. The U.S. trade embargo on Cuba was enacted in 1960, strictly limiting travel and commerce between the two countries.

But one College member has crossed the border, explored the Cuban medical scene, and reported back on what he found. Paul K. Drain, ACP Associate Member, recently wrote an article in Science describing the Cuban medical system and calling for an end to the trade embargo.

Dr. Drain, who is now an infectious disease fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, recently spoke with ACP Internist about his experiences in Cuba and the public reaction to his article.

Q: How did you become interested in Cuba and end up going there?

A: I became interested in Cuba during my public health training at the University of Washington in Seattle. I was part of the International Health Program and we'd regularly talk about success stories among developing countries, such as Kerala state in India and Cuba. As we discussed their statistics for health care outcomes, it seemed as though Cuba was providing excellent care for their people, yet spending little money.

I didn't have the opportunity to go to Cuba until I attended a global health education conference sponsored by the WHO (World Health Organization) and PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) in 2008. I gave a talk about global health education and opportunities. While I was there, I saw some of the clinics in and around Havana and was just really impressed with their health care infrastructure.

Q: What were the most notable differences from the U.S. health care system?

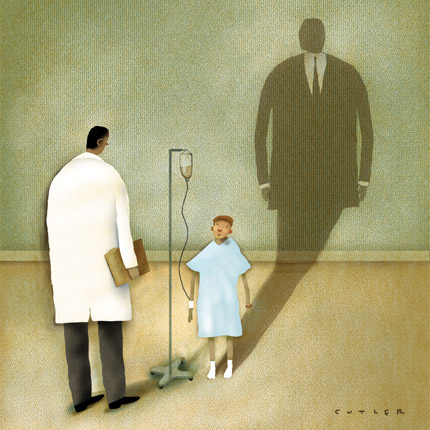

A: What becomes rather apparent when you get to Havana and see the structure of the health care system is that the Cuban people generally have very good access to primary health care. Each person is assigned to a primary care doctor, so they can develop a long-term relationship with their physician. Because the Cuban physicians are responsible for a relatively small patient panel, patients can easily get in to the neighborhood clinic to see their doctor. There's a second primary-care layer within the local system, called the polyclinic. The polyclinic serves as an organization hub for the neighborhood clinics and provides additional primary care and some specialty care services.

One afternoon, I visited one of the emergency rooms at a polyclinic. When I arrived, I was surprised to see that it was empty. I asked one of the Cuban doctors, “Why are there no patients in the emergency or waiting room?” He said, “Typically, if someone has an acute problem, they can usually be seen by their regular neighborhood physician that same day.” Furthermore, people went to the polyclinic for emergent issues, but the polyclinic physicians would either treat them and send them home, or refer them for admission to one of the local hospitals. Each polyclinic had an ambulance that could transport patients to a local hospital.

Q: How does the experience of being a physician appear to be different in Cuba?

A: Primary care doctors in Cuba spend most of their mornings seeing patients in their clinics, but generally have a free schedule in the afternoon. Because they're not scheduled to see as many patients throughout the day, they can follow-up with their regular panel patients in the afternoon. In fact, many spent some of their time in the afternoon visiting patients in their homes.

If a patient didn't show up for a scheduled appointment, then oftentimes, either the nurse or physician would visit their home to ensure that they were OK.

In addition, the Cuban physicians are working under a budget that is about 10 times less than what we're spending in the U.S. They have many challenges in terms of using generic medications and not utilizing as many diagnostic studies. The lack of financial resources puts more pressure on them to diagnose a patient's condition based on their history and physical exam, rather than expensive diagnostic studies and imaging modalities.

Q: As a visiting American physician, what response did you get from Cubans?

A: The Cubans I spoke with were very proud of their health care system. The physicians I spoke to liked to point out that, as a result of providing excellent primary care, life expectancies in Cuba are about the same as what they are in the U.S.

Of course, the Cuban doctors acknowledged that they still had many problems within the system. There were many things they wanted to improve upon—like more access to diagnostic tests, certain medications, and technology for some of the more complicated procedures. Many of them also felt very constrained in terms of capacity to do medical and scientific research. They wanted more opportunities to collaborate with U.S. scientists. Lifting the U.S. trade embargo may make it easier for open communication and research collaboration between Cuban and American scientists.

Q: What did you hope to accomplish by writing about Cuba?

A: We are hoping that our article in Science will continue to generate discussion around the U.S. trade embargo. An exchange of ideas could lead to the development of new medical advances and discoveries, as well as a stronger primary care model in the U.S.

Q: What response have you received to the article?

A: The responses have been very polarized. I've received dozens of e-mails from Cuban physicians who have been very grateful for our article. I have also received many e-mails and comments from people who are not supportive of the article or the Cuban government. They have written me with some rather vicious language, and clearly they feel that any sort of relaxation of pressure on the Castro regime would be wrong. Interestingly, as far as I can tell, all the negative e-mails and letters have come from people in the U.S., and not from people in Cuba.

Q: How has your experience in Cuba affected your own practice?

A: I've spent several years working in Africa, and each time I go to Africa or Cuba, I'm reminded that we can diagnose most diseases through our history-taking and physical examination. The expensive tests we often do in the U.S. to confirm our suspicions are helpful, but are less important than we commonly think.

If we can find ways to make our health care system more cost-efficient, like ordering fewer imaging tests, then we can begin to devote more of our effort and finances towards keeping our patients healthy.

Q: Do you see any prospects for greater collaboration between the U.S. and Cuban health care systems?

A: Since President Obama took office, there has been a lot of legislative talk about amending or repealing the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba. In our Science article, we mention some of the bills that are being discussed in the congressional Foreign Affairs Committee. Congressman [Howard] Berman, the head of the committee, seems willing to move these bills forward, but it may take some additional public pressure.

There has been more national discussion about Cuba, and recent polls show that Americans favor eliminating the travel restrictions. The more we can make this a public dialogue, rather than just a governmental dialogue, the better chance there will be for eliminating the trade embargo.