Sorting out the worst offenders among herbal supplements

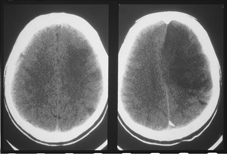

Post-stroke care often fragments after patients leave the hospital. Patients being treated by specialists should keep the primary care physician at the center of their follow-up regimen.

Most internists have a tough enough time keeping up with developments in pharmaceuticals that they don't have the energy, or possibly the inclination, to get up to speed on the ever-expanding range of herbs and supplements their patients might be taking. But they ought to be well informed, for their patients' and their own benefit.

Here's the reality check: More than a half-dozen commonly taken herbs or natural remedies from coenzyme Q10 to dong quai to ginkgo biloba and even garlic pills can interfere with warfarin to increase bleeding risk. A growing list of supplements, St. John's wort chief among them, has been shown to affect the efficacy of statins.

The commonly taken anti-anxiety supplement kava kava, used for eons by Pacific Islanders, could shortchange the benefits of prescribed Parkinson's disease medications and antidepressants and can be downright dangerous if used with alcohol. It might even damage the liver if taken in sufficiently high quantities.

Ginkgo, thought to be relatively benign a decade ago, has been shown to significantly increase the risk of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies.

Bitter orange, which took over in the weight-loss supplement scene when ephedra was proved dangerous, isn't any less so: It can interact dangerously with heart medications, causing life-threatening arrhythmia and possibly leading to myocardial infarction or stroke. And patients with a history of breast cancer or who are being treated for it could be treading dangerously if they consume black cohosh or red clover.

“Some physicians are very busy and don't want to take the extra five minutes to ask about these things. And some don't even want to open that box because a patient might, for example, talk for 20 minutes about why passion flower and willow bark are so important to them. But it's important to know what patients are taking and why,” said Douglas Paauw, FACP, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle who frequently speaks on drug-drug and drug-herb interactions.

“There are plenty of 60-, 70- and 80-year-old patients taking large volumes of supplements,” he continued. “As a rule even though there are no rules you're less likely to see an 80-year-old patient walk in on 15 supplements than a 40-year-old, but you can certainly be surprised.”

Determining the dangers

One way to quantify the trend of potential herb-drug dangers involves the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, a leading source of evidence-based information in this area, which identifies more than 1,600 potential interactions, ranging from mild to major. (See “Herbal supplements' worst offenders” sidebar.)

St. John's wort and vitamin E, which many patients take, are Dr. Paauw's top two potentially dangerous or likely useless herbals or vitamins. The former is associated with such a broad range of dangerous interactions that it's the one supplement Dr. Paauw would abolish if he had the chance.

“As far as causing trouble and being potent, this is the one,” he said. St. John's wort potently affects the P450 system that metabolizes drugs in the liver, generally increases the metabolism of warfarin, and can make statins less effective. In addition, some reports have shown it to decrease warfarin metabolism.

Lisa Corbin, FACP, medical director of integrative medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver and a well-known authority on herb-prescription drug interactions, is also vehemently opposed to St. John's wort. She calls it the “poster child” for potential harm when it's combined with any number of commonly prescribed drugs.

For vitamin E, the consuming public may still be taking more than 1,500 units daily, even though it's been roundly proven ineffective in improving heart health. “It's one of those things that's been found to have almost no clinical benefit, and may cause potential harm, bleeding risk, in particular,” Dr. Paauw explained. “So its therapeutic index is on the negative side.”

Dr. Corbin said, “There really isn't any good reason for patients to be on a vitamin E supplement,” and also gives somewhat low safety marks to kava kava, which she says is “basically a benzodiazepine,” and to ginseng, ginkgo, garlic and vitamin E or fish oils, all of which “have the potential to act as anticoagulants.”

Barak Gaster, FACP, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington who teaches evidence-based herbal medicine, adds red yeast rice to his worry list. The substance, a dietary staple in some Asian cultures, is definitely quite potent.

“This dietary supplement's extracts contain small quantities of naturally occurring substances which are identical to lovastatin such that the FDA has issued warning letters to its manufacturers that it considers it a drug, not a supplement,” he said.

What patients take and how to find out

If internists want to find out what their patients are taking, they'll have to, first and foremost, adopt a non-judgmental attitude, advised geriatrician and integrative medicine specialist Wadie Najm, MD.

“When I talk to patients about what they are using to help with whatever conditions they've been diagnosed with, the most important thing is to let them know that I am not going to pre-judge them,” said Dr. Najm, medical director of the Susan Samueli Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, Irvine, and an editorial board member of the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.

He asks patients what they're taking in the way of herbs, vitamins, supplements and even teas “to help them with anything else.” And if they're willing to disclose that information, he figures he's on first base. If not, he goes to strategy number two, which involves using an example. “I say, many of my patients are finding glucosamine helpful for their arthritis; have you tried this?” Dr. Najm explained. “When I do this they might be a little more forthcoming about anything else they're taking.”

In patients with a potentially serious or life-threatening diagnosis that warrants a powerful therapeutic response, the issue becomes even more pressing, according to Michael Fisch, FACP, MPH, chairman of the department of general oncology at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr. Fisch starts out by being generally inquisitive. “I often ask the patients more questions than they ask me, about how they felt after the diagnosis and what advice they got from family and friends,” he explained, when patients learn, for example, that a surgical procedure didn't remove all of the cancer or that chemotherapy might not be very effective.

“I try to understand where they're coming from, what they might want, and where they're open,” he said. “For example, a patient might tell me that ever since she started taking acai berry, she has much more energy and ask whether she might also consider taking curcumin [also known as tumeric]. Then I try to find the most evidence-based and least toxic [supplement] to explore further with the patient. And I am also willing to tell them what I don't know.”

Dr. Corbin suggests that internists be prepared to take the conversation a step further, if they're concerned about an herb or supplement the patient is taking but don't want to sound as if they're delivering the “all supplements are bad” message.

“It's nice for an internist to have a safe supplement in his or her back pocket to be able to say, ‘I don't want you to take X because it may raise your blood pressure,’” she explained. “‘Consider fish oil, calcium, and magnesium instead, as these supplements are safe and have been shown to lower BP slightly.’”